Some Extraordinary Vlachs

In the past few months, I have been thinking of some of our people who have done extraordinary things and have distinguished themselves in a wide range of undertakings. Let me share some portraits of these people with you.

Dermatology and Miniature Cameras

I will begin with the late Dr. Haralambie Cicma, a dermatologist. As a young man he decided that working in factories, running restaurants, and other similar occupations were not for him. He aspired to become a doctor and began his career by gaining admission to the prestigious medical school of Harvard University. In doing so, he had to overcome the handicap of his immigrant English, which didn’t exactly meet Harvard standards. But his energy, determination, and pride paid off and after receiving his M.D., he set up a practice in dermatology on Angell Street in Providence, Rhode Island.

Dr. Cicma’s talents were not limited to medicine, however. He was also very good in chemistry and he not only developed a number of salves and ointments to treat skin disorders, he set up his own machinery to produce them. [Editor’s Note: Dr. Cicma’s fascinating autobiography was recently published in installments in the Newsletter of the Romanian-American Heritage Center in Jackson, Michigan; we recommend it to our readers.]

In his spare time, Dr. Cicma became interested in photography and soon became an expert in the field. He pursued this hobby with such ardor that toward the end of his life, he had collected just about every type of camera that was produced in the United States and foreign countries. Indeed, his collection would constitute a modern museum of photography.

Of all his cameras, he focused his attention on the miniature camera the size of a cigarette lighter, to which he could attach a telescope, if desired. I remember a large photograph of a ship he once showed me. I considered it a shar picture with excellent photographic qualities. He then told me that the ship was actually miles away when he snapped the photo!

Photography proved more than a hobby. During World War II, he was commissioned by the United States Department of Defense to develop a flash for this miniscule camera. His interest in photography also led to a special relationship with National Geographic magazine. He had a restless mind, but despite this and his many accomplishments, he always retained the warmth and charm I believe are characteristic of the Vlachs.

From Microwaves to Sundials

His name is Paul Zottu, he now lives in Dedham, Massachusetts, and he hails from my hometown of Baieasa in Greece. He is a retired electronic engineer whose specialty is microwaves. You probably have a microwave oven and you probably marvel at the way it cooks your food in the very same dish from which you will eat it. And no doubt, you think that the microwave is the last word in electronic wizardry. If so, you are entirely wrong . . . Paul knew about such things some fifty years ago. In fact, he was an important pioneer in the field. When he started building microwave ovens, they were not the size of a shoebox or two, as your oven today probably is. His ovens were the size of a small house or shed.

Because the main industry of our hometown in Greece is lumber, Paul was well aware that it takes green lumber nearly a year to dry to the point where it can be used in construction. He believed that through the use of microwaves, the drying period could be reduced to minutes, and het set about designing and building a microwave lumber drying machine. His equipment was a boon to the lumber industry, and his business was very successful, with his product in demand throughout the United States (he set up headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia).

After retiring from the microwave industry, Paul found other pursuits. With spare time on his hands, he became fascinated with astronomy, with a special interest in the sun’s relation to the earth. This interest focused on sundials. Paul began designing and producing sundials of great beauty as well as accuracy. They were made of solid brass, which took on a ploish like that of 18-karat gold. One such sundial was acquired by the city of Boston and set up in one of its parks (such a gem was not overlooked by thieves and it was soon stolen).

The people of Baieasa are extremely proud of Paul Zottu.

The Teenage Boy and His Airplane

Nicholas Economou and his wife, my sister Viola, had a huge farm in East Georgia, Vermont. They had five sons: Arthur, John, Michael, Ferdinand, and Nicholas, Jr. Arthur, the eldest, became intrigued with aviation when he was 14 or 15 years of age and he devoured every book he could find on the subject. He wanted very badly to learn how to fly. There was even a meadow on the farm suitable for a landing strip, but the price of a plane was beyond the family’s reach. So he decided to build his own.

The plane was to be a high wing monoplane and he started building the wing in the attic of the farmhouse. It consisted of two Sitka spruce spars onto which were fastened ribs, also made of spruce. The framework was then covered with a cotton fabric, the same material of which high-quality men’s shirts are made. It had to be fitted over the entire frame carefully and then sewed neatly with all the edges pinked. This required the skills of a master tailor, and yet the boy engineer did the job effectively and diligently.

The final phase of this sort of wing construction is called “doping.” The “dope” was something like a colorless paint with a terrible smell. It shrank the fabric, giving the wing a tight skin of great strength. (The goal was to produce the strongest wing possible with a minimum of weight.) When finished, the wing was truly a thing of beauty, like the shimmering wings of a dragonfly.

The boy engineer had overlooked one thing, however: how to take the wing out of the attic. In the end, it was necessary to take apart a portion of the farmhouse in order to get the wing out.

The air-frame or fuselage was made of steel tubing that required welding. The only parts that Arthur did not make were the propeller, landing gear (wheels), and the instruments. The task took three years and when finished, the plane was tested and flown by a professional pilot. Arthur’s interest in aviation continued as an adult and he became a licensed pilot. I might add that my nephew’s enthusiasm for planes was contagious and I, too, caught the aviation fever.

The Famous Vlach Photographer of New York

George Michaels (Miha), my wife’s uncle, worked in a shoe factory in Haverhill, Massachusetts. But the thing that fascinated him most in life was photography, and so he began to study it and to conduct experiments in it. He then built his own camera and made a living photgraphing weddings, outings, baptisms, and so forth. When he had accumulated some capital, he moved to New York, set up a studio/workshop, and distinguished himself by photographing important people, including political and religious figures and celebrities.

George was a born engineer and inventor. He acquired a number of patents associated with photography. He invented a device that would photograph data on the very edge of portrait negatives, such as numbers and dates. This invention was welcome by studios throughout the country, for it enabled them to have better control of their products.

But I believe his greatest contribution to the science of photography was his work in film development. The research staff of the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New york — some of the most renowned people in the industry — wrote a photographic manual stating that the ideal temperature for developing film was 66 degrees Fahrenheit. But a single individual disagreed: Uncle George had conducted his own research and came up with 68 degrees as the ideal. He wrote to Eastman Kodak and said they were in error. Shortly afterward, their textbooks were rewritten with the correct temperature of 68 degrees. George told me that Kodak never acknowledged the voluntary contribution he had made. But every time I develop photographs at 68 degrees in my cellar, I think of George Michaels.

The Weaver-Inventor

My good friend and fellow townsman Emil Gemakis was another extraordinary Vlach. Emil came to America with his mother and his sister Sylvia on the same boat as my family did, in 1920. They settled in Keene, New Hampshire, while we settled ten miles away in Westmoreland. From an early age, Emil became very deeply interested in the craft of weaving and whenever he came across a piece of fabric, he would examine it carefully, analyzing its texture. From Keene, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where Emil found a job with an important weaving company. While working as a weaver, he was always thinking about how a fabric could be made betetr and faster and he came up with some important ideas and ways of improving the machines he worked with. Through his creativity, his company was able to obtain several patents. Fortunately, the company recognized his contribution and he was rewarded with a promotion to the position of Vice-President. He was a candidate to become President of the company when he died.

Emil had no technical training whatsoever beyond what he learned on the job. His formal education terminated with a high school diploma. But his store of Vlach talents and ambition paid handsome dividends.

From Feta Cheese to Cinematography

My father John and my eldest brother Andrew started out working in shoe factories in Haverhill and Worcester, Massachusetts, but certain circumstances helped them decide to go into the dairy business. During World War I, the German submarine blockade made it impossible to import cheese from Europe, and yet there was a great demand for European cheeses among immigrants in America, and especially among Greek-Americans in our area. Although they had no experience whatsoever in the dairy business, my father and brother set up a cheese manufacturing plant in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, buying milk from local farms.

There were many other Greeks and Vlachs in New England at the time and there was intense competition. My father and brother studied the quality of the cheeses that were available and discovereed that the cheeses made by their competitors contained a high bacteria count and would spoil when shipped in freight cars (there was no refrigeration on trains at the time). The bacteria count was high becaise the milk they used was not pasteurized, so my brother Andrew decided to learn the process of pasteurization by attending the University of Wisconsin for one semester. The cheese from pasteurized milk was a big success. Our competitors could not understand why our cheese did not suffer in shipment while theirs boiled with bacteria and of course spoiled.

From their profits, my father and brother next ventured into the moving picture business by building an elaborate movie house (Vlach pride — it had to be the best). The entire family operated the movie house, which was a big success. We ended up with seven motion picture theaters in Vermont and New Hampshire. Again, we knew nothing about moving pictures, but some of our Vlach cultural resources proved decisive.

From Sheep to Greenhouses

Finally, there are the fantastic adventures of Nicholas Economou and his wife Viola — my sister. After the usual stint in shoe factories, they opened a store in Nashua, New Hampshire, made some money, and then bought a huge farm in East Georgia, Vermont. The farm included a small mountain and a huge tract of land next to the Lamoille River. They opened the farm for the purpose of raising sheep, not being aware that the climate of Vermont was not suited to the task. Nicholas and Viola’s five boys did most of the work, while Viola cooked for them.

Nicholas, who was always dreaming up wild ideas, next decided that he would go into the appliance business, though not in Vermont. He decided that Romania would be a good place for such a venture, because oil was plentiful there. He would sell oil-burning stoves and other similar appliances. He bought a supply of stoves and took off for Bucharest, leaving his wife and boys on the farm. After establishing his business in Bucharest, he asked his family to join him. Of course the boys had to interrupt their schooling and the family suffered in other ways from the radical change in geography and living style.

The oil stove venture was a total failure. The Romanians preferred to burn wood, which was scarce and expensive, to oil, which was abundant and cheap. The family found itself in a very difficult situation. With true Vlach adaptability and determination, they decided that what the Romanians needed was hot doughnuts. And so, with what little capital they had left, they imported some doughnut machines from the United States and began selling hot doughnuts on the streets of Bucharest. The Romanians liked the hot doughnuts and the venture was a big success. They went on from there.

With the experience they had farming in Vermont, they decided that they could raise vegetables under glass and beat the Romanian farmers to market every year. Using the manpower of the five boys plus a few Romanians, they built a greenhouse and followed it with several more. The Economou boys used to tell me that their father was a real slave driver, demanding many hours of hard work from anyone working for him. But the adventure was paying off. The first year, they were able to get tomatoes on the market before other farmers could.

The Romanians loved flowers and the Economous saw an opportunity to meet this need alongside their vegetable growing. In the winter of 1944, they succeeded in raising red carnations and it occurred to Viola to present a bouquet of red carnations to King Michael. Nick and Viola went to the King’s palace in Sibiu and personally presented the King with the flowers. The King and his court considered this a miracle. No one had ever produced carnations in winter. The Economous became celebrities overnight and all the newspapers wrote of how a Macedonian Romanian had produced the impossible. Nick and Viola were decorated for their achievement.

But this fantastic story has a tragic ending. The boys did not acclimate well and yearned for the United States. Not having enough money for their passage, they stowed away from the port of Constantsa in different ships. And Nicholas and Viola were murdered in their home in Pantelimon sub Urbana in 1945, supposedly by farmers in the general vicinity who were envious of their fame and wealth. But when my family and I visited Bucharest in 1970, the people of that city had not forgotten the Vlach family that had performed a “miracle” in 1944.

Top row, from left: Nick Economou; Marian, Lucia, Peter, and Steven Tegu.

Middle row: Arthur and Viola Economou; Mr. & Mrs. John Tegu; Andrew Tegu.

Front row: Nicholas Economou, Jr. (on Viola’s lap);

Mike, John, and Ferdinand Economou.

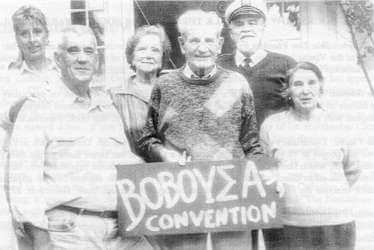

Photo taken at a recent “convention” of natives of the Vlach village of Baieasa (Vovousa in Greek). From left: Mrs. Pindou Petrou and Dr. Pindou Petrou, a dermatologist in Astoria, NY; Nina and Ian Petrou — Ian was a reporter for the now-defunct Greek newspaper Atlantis, and is currently one of the editors of the Epirotiki Etaireia in Greece; and Mrs. Steven Tegu and Prof. Tegu, the hosts of this gathering in Providence, RI.

Responses