Touring the Vlach Villages of Greece

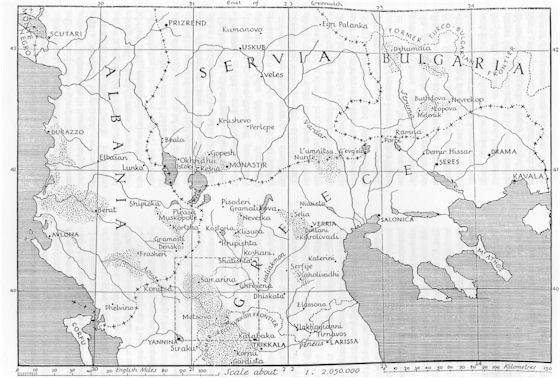

Seventy-eight years after the publication of Wace & Thompson’s Nomads of the Balkans, the Vlachs and their villages have suddenly inspired cultural interest and academic inquiry. Indeed, we owe a debt of gratitude to those two British scholars who, to our good fortune, left an archaeological dig in Thessaly to study our people. As one who has followed their route many times over the years, I offer this updated travelogue of the Vlach villages of Greece.

Your trip to Greece will in all likelihood start in Athens, which is home to roughly half of the entire population of Greece. There is much to do in Athens, but once the historical tours are over and your sights are set north, the bus station (praktoreio) for Volos and Larisa is usually a good place to start out your travels — and a good place to meet Vlachs. In fact, that seedy, decrepit station has often been my first point of contact with Vlachs in Greece. Many old Vlach women — so incongruous in Athens, dressed, as always, from head to toe in thick black wool — board buses there, heading home to Larisa, Volos, Trikala, Pharsala, or to mountain villages, after visiting sons and daughters settled in Athens. I have met Vlachs all over Greece, even on distant islands, far away from any Vlach centers, and meeting them by chance in Athens should come as no surprise. In cafes or on the street, in normal conversation or by chance, with a little luck, you will meet one of our people. When in Athens I usually stay in the Coreli Hotel, in the fashionable neighborhood of Palio Faliron — the beach is right across the street. There on one summer day I struck up a conversation with a Vlach lawyer from an obscure village in the Pindus Mountains. Though he was well-established in Athens, he visited his village every summer for a few weeks, and even after 20 years in Athens he still spoke Vlach as if he had never left his village. Such people can be found throughout the city.

Volos is a base camp for my travels in Greece, a good place to find Vlachs. And there are many. Because I have relatives and friends there, Volos was the first place in Greece I came to know well, and it has much to offer the visitor. But the bus out of Athens will stop in a more familiar place to Farsherots before it reaches Volos. Almyros is a large town in southern Thessaly, oppressively hot in the summer, and a place not too far removed from the collective memory of those from the Albanian Vlach village of Pleasa. For most of us, the two villages are practically synonymous, since Almyros was the winter village of most Pleashiots. I first heard its name as a child from my grandmother, and I’ve returned to the old town on every trip to Greece. I still recall the excitement of my first visit: generations of family, remembrances of grandparents and their friends, the emotional pull of its name and image, and, finally, walking into my grandfather’s house, seeing it as if having been there before. Almyros assails you like a graveyard of shadows. But brace yourself for a surprise — especially those of you accustomed to the reminiscences of parents and grandparents: Almyros is not, and has never been, a Vlach village. It has a moribund Vlach quarter, the same part of town where the Vlachs have always lived, but the rest of Almyros, now thriving, has always been Greek. Nor does even the old Vlach mahala feel Vlach any longer — there’s probably not a person there under 40 who can speak the language. Because something happened there over the last 50 years or so — perhaps some period of reckoning after World War II — where the Vlach presence among Greeks brought emotions to a boiling point, and the language finally succumbed, apparently without a battle. Vlachs assimilate easily, and even in villages which are fanatically pro-Greek, there is usually some vestige of pride remaining, but in Almyros there is left only a residue of sensitivity and bad feelings about Vlach, as if the language had been officially declared forbidden. It is a strange world indeed that the old-timers have accustomed themselves to. But if you are a nostalgist looking for a bit of the old Almyros, a weathered memory of its old status as a Vlach center, try opening up the town phone book. You’ll find familiar names, Farsherot names, grandchildren of those who never left, who never came to help colonize the American Vlach community. A simple indulgence of one’s curiosity can often reveal a great deal of hidden history. In any case, Almyros is well worth a one-time visit for those who feel an emotional pull to it. Hopefully, the newly-formed Syllogos Vlachon (Vlach Society) of young Vlachs — none of whom can speak the old language — will be able to piece together the ancient fragments of their culture in a thoughtful, modern way.

Outside of Almyros, Wace and Thompson identified three villages, two Vlach and one Sarakatsan (Greek shepherds who are sometimes erroneously confused with real Vlachs — see J.K. Campbell’s famous book, Honour, Family, and Patronage). The first, Eftinopoulis, is Sarakatsan. The other two, Neriada (Kerminli) and Anthotopos (Kililaiu) were once entirely Farsherot villages, and many of the Pleasa Farsherots, when speaking of Almyros, actually meant these two villages. My grandmother was born and married in Neraida and the inside of her old home, now occupied by a Greek family, filled me with sadness, as if it were a lost possession — a pretentious and absurd claim. Many of us still have relatives there, but the Vlach identity is gone. These are small and featureless villages from a traveler’s perspective, with no accommodations (unless you know someone). A practical reminder here: Do not visit these or any other villages in the heat of the afternoon — everyone is asleep.

Volos, a large town of about 80,000 inhabitants, figures in Greek mythology as the launching point for Jason and the Argonauts in their search for the Golden Fleece. It is a port city from which ships and ferries sail to the Middle East as well as neighboring Greek islands. It is located at the foot of lush Mt. Pelion — one of the most scenic locations in Greece. Pelion, mythic home of the centaur, has 24 well-wooded villages, but contrary to popular belief, none of them is Vlach (though some wealthy Vlachs have purchased homes there). And yet, Volos itself has a large Vlach contingent, anywhere from twenty to fifty percent of the residents.

There are several modern hotels in the city, but the Hotel Iason, on the waterfront, is run by an old Farsherot family who no longer speak the language nor, for that matter, willingly reveal their ethnic origin. They offer an idea of how long and how thoroughly many Vlachs have been assimilated. Numerous family portraits in the unpretentious lobby seemed to me unmistakably Vlach; I cornered them, and they admitted it. The hotel is spartan, adorned in the old style, and bathrooms are shared in the hallway. There is still one old Vlach quarter in Volos, in the neighborhood known as Aghia Paraskevi, near the top of the town, approaching the foot of Pelion. The young, however, are not likely to know much of the language, nor are they particularly interested.

As for pure Vlach villages near Volos, the closest is Sesklo (Sheshklu), only about four miles away. Sesklo is Farsherot, and there, too, Bridgeport families will find close or distant relatives and familiar family names. It is unquestionably more cheerful than Almyros about its Vlach identity, and most people in the village — including the young — speak the language without looking over their shoulders. In Sesklo, I have had the pleasure of speaking Vlach with five-year-olds; it is a quiet stronghold of our language, thriving on its own without any affiliation with other Vlach societies. Anyone who doubts the strength of Vlach in Sesklo need only ask the three or four Greek families living there — they, too, speak the language! There is a misohori (village square) with a couple of shops and a restaurant, but no accommodations.

One other Vlach stronghold near Volos (9 miles) is Velestino, the birthplace of Rigas Feraios, the first martyr of the struggle of modern Greece for its independence. Velestino, the winter home of many residents of the Vlach village of Perivoli, is only about 75 percent Vlach. One notes immediately, moving from Sesklo to Velestino, clear dialectal differences. For American Farsherots not familiar with other dialects of our language, traveling through the many Vlach villages of Greece offers a linguistic education.

North of Volos is Larisa, the capital and largest city of Thessaly; it is filled with Vlachs, mainly from Samarina. A virtual steambath in summer, Larisa is a modern, bustling city. But the roads heading north out of the town pass through an area that is heavily Vlach. Mikro Perivoli (Taktalasman) is a sun-drenched Vlach village in the hills north of Volos, on the way to Larisa, and Falani, just two miles outside of Larisa, is inhabited by Samariniats. Tyrnavos, a town to the north, is perhaps 60 percent Vlach, mainly those from Avdhella and Samarina. Other than its good wine and araki, it is a featureless town, good for a few hours’ stopover at best. Four other villages, Rhodia, Makrihori, Parapotamos, and Vlachoyianni, are near Larisa and Tyrnavos, and Vlach can still be heard in each of them.

Off the main road from Tyrnavos to Elassona, 70 percent of whose residents are Samariniats who head for their ancestral village in the summer, is Argiropoulion (Karajoli), which is not to be missed by any Farsherot traveling in Greece. Dr. Tom Winnifrith found it strongly Vlach in language and feeling, and so did I on my four or five visits there. (Evidently, Wace and Thompson missed it altogether, though it may have been no more than a mere collection of summer tents in their day.) Young and old still speak the language. Argiropoulion’s Farsherots have not been settled in Greece much more than 100 years, which helps explain their attachment to Vlach; but they are, like all the rest of us, on the verge of a most critical period. The next decade or so will in all likelihood dictate the future direction of the village’s identity and language. In the ten years between my first and last visit there, change was evident and the village appears to be going through a subtle transition.

From Larisa there is a road which turns westward, crossing over the Green and fertile Thessalian plain and finally reaching Trikala. Back in 1914, Wace and Thompson found this provincial town to be about 70 percent Vlach, though today it would be far more difficult to even make an estimate — assimilation does take its toll. But Trikala is still home to many Pindus Vlachs, including my good friend Zoe Papazisi-Papatheodorou, the well-known writer of Ta Traghoudhia ton Vlachon and other works.

Kalambaka, touristy because of Meteora’s clifftop monasteries, is only minutes away and, like Trikala, is filled with Vlachs from the Pindus Mountains. In the center of Kalambaka, the International Restaurant is worth a stop, both for its food and its owners — friendly, enthusiastic Pindus Vlachs — you’ll hear them in the kitchen conversing among themselves in our language.

Just south of Kalambaka, Glykomilea and Klinovos are both Vlach villages with origins in the Pindus. But beyond, in the undulating hills of Hasia, the area between Trikala and Kalambaka, you’ll find a very small village (50-70 families) which is still something of an anachronism, even by Vlach standards. Nea Zoi (Burshan) is Farsherot and still heavily transhumant — certainly one of the last such settlements in Greece. In summer, most of the men are away pasturing their flocks, leaving behind only women. Of course, everyone in the village speaks Vlach; but on my last visit there, I noticed a change — a few of the young now refuse to go with their fathers and flocks, and it is likely that this village, too, will soon abandon the old ways. They know only too well that the ancient practice of shepherding is neither practical nor appealing in the modern world. The village is in transition, confronting the inevitability of modernization. Indeed, New Zoi may not have much of a future — many Vlach villages are nearly deserted now, and during my last visit there, the ominous thought crossed my mind that it could happen here, too. The young must find some reason to stay.

From Kalambaka there are three or four buses daily to the Vlach showcase of Greece, Metsovo (Amintshu). The ascent out of Kalambaka is immediately steep and winding, but the scenery is breathtaking! The Pindus Mountains appear regally in the distance. The road, long and paved, passes near Metsovo before it eventually descends into Ioannina. But even before Metsovo, about two hours out of Kalambaka, you’ll pass through a string of smaller Vlach villages, most of which still speak Vlach, and all obscure, save one — Malakassi. The others, Megali Kerasia, Orthovouni, Mourgani, Korydallos, Trigona, Pefki, and Panaghia, are interesting in that they are practically anonymous. Like Metsovo, they still retain Vlach simply because they swiftly resisted any movements to establish Romanian schools — by a cruel irony, those who tried to save our language actually did it almost irreparable harm by dividing our people against one another. It is indisputable today that Vlach is strongest where no Romanian schools were established — and weaker where they were.

A word of caution here: Vlach villages in Greece, no matter how well or how poorly they have retained their language, do not identify with Romania or Romanians in the slightest; they are Vlach Greeks, just as we are Vlach Americans, and they are Greek first and foremost, just as we are Americans first and foremost. Mistakes have been made by Vlach visitors to Greece, from naive errors (such as asking for “Romanians” in Metsovo; our people simply replied that there were none) to stubbornness and downright insensitivity (such as talking down to our people and telling them they are really Romanian, not Greek; they will likely run you out of town). Our people are generally very happy in Greece. Put aside any Romanian notions you may have been taught back home; open your eyes and your mind. If there are Vlach patriots in the village — and indeed there are many — they will surface. This was brought home to me on one of my early trips to Metsovo. Waiting in line behind a number of Greek tourists trying to register at one of the village’s many hotels, I was told there were no rooms available. As the desk clerk turned away the tourists, I approached, speaking in Aromanian. I can still recall his words: Tri unu patriotis a’emu unu locu! (“For a compatriot, we have a place!” — Note that in Metsovo they drop the “v” in avemu, “we have,” and they also inflect verb and noun endings strongly.) But remember that they are Vlach patriots — not Romanian.

Several miles before the turnoff into Metsovo, there is a sign pointing toward the village of Milia (Ameru). If you head that way, Milia is about an hour’s drive over an unpaved road (it may be paved now). Vlach is strong here, spoken by practically everyone in the village. The dialect is almost identical with that of Metsovo, and Milia may be one of the last Vlach villages where an old woman or two still struggles to speak Greek. Today, Milia remains a healthy Vlach enclave. Also nearby, but less vigorous than Milia, is Krania (Turia), an old Vlach village with Gypsy musicians. It is a very quiet place now, but at the turn of the century and up to World War I, the village, then proudly Vlach, fought vigorously to keep its Romanian school. Turia was that rare place where the Romanian school dominated; in most villages, the opposite was the case — the Greek school thrived. But Turia paid a violent price for its persistence, still part of its collective memory.

Today, Metsovo (Amintshu) is the largest year-round Vlach village in Greece or any country. It has changed in many ways over the past ten years, and this is lamented by many, but at the same time it has succeeded in keeping most of its young in the village. No Vlach visiting Greece should miss it. The serpentine road which finally descends upon Metsovo (population 5,000) offers a gorgeous panorama of mountains and a glimpse of its Mediterranean-tile roofs and Swiss-chalet style houses. The village is noted for its handsome homes and at once you will stop and gaze admiringly at its delightful combination of stone and woodwork amid an abundance of thriving gardens and impressive trees. Halfway down the mountain, toward a large ravine, is a 13th-century monastery, Aghio Nicola, tranquilly cloistered in a wooded area away from the noisy village square. Metsovo, despite its tourism, reminds me of a storybook village — it is that beautiful, dressed in a panolpy of seasonal colors. The misohori is large and roomy, but stay off the bench on the west side of the square: it is reserved for Metsovo’s aged and venerable retired shepherds, resplendent in the old garb of the village, complete with pompomed shoes, kilt, and fez. Unfortunately, with each visit I notice fewer of them.

With dozens of shops, restaurants, and hotels, Metsovo is a comfortable place for a few days’ visit. If you check in at the Hotel Bitouni, Taki Bitouni and his wife will be delighted to speak Aromanian with you, as will their two sons who attend college in England. The Hotel is rustic and traditional, immaculately clean and comfortable, with a fireplace in the ornately-designed lobby. But I have another recollection of Metsovo, a firm reminder of its Hellenism amid this evidence of a Vlach identity: Back in the mid-1980s I met the late Evangelos Averoff-Tossitsa, former Minister of Defense of Greece, a wrier and poet who was a native of Metsovo. As we shook hands he firmly admonished me for speaking Aromanian with him, although I later heard him speak it perfectly with an older gentleman. His words in Greek, Prepi na milate ellinika (“You must speak Greek”), caused me to walk away in anger. Thankfully, my anger quickly subsided. But this experience was a valuable firsthand lesson in how to approach and deal with strongly pro-Greek Vlach villages, and it helped open my eyes to the situation of our people in Greece.

Directly across from Metsovo, over a deep ravine, stands Anilion (Nkiare), the subject of a feature article by Dr. Tom Winnfrith in a past issue of this Newsletter. It is a strenuous one-hour walk from Metsovo, straight down one mountain and up another.

Before getting back on the road from Metsovo to Ioannina, a detour is needed in order to visit some of the most interesting but least known Vlach villages in Greece, which lie in a region called the Aspropotamo (White River). Aside from Tom Winnifrith, I know of no outsider who has visited our villages in this region since Wace and Thompson. The roads leading to these villages start out of Trikala, Kalambaka, or Ioannina, and though they may start out paved, before long you’ll be riding over rocks, ditches, and donkey trails — unvisited places set in the wildest, most anarchic landscapes in all Greece. I foolishly attempted to leave one of these villages on foot one afternoon. No trucks or cars braved the roads that day and, stranded, I was forced to spend an incredibly peaceful night under a tree in the most remote region of Greece. Fortunately, the next morning a truck coming out of a village gave me a lift.

The two best-known villages in the area are Syrakou and Kalarites, which face each other across a mountain gorge. Both villages are very old, their glory days long past. Syrakou was the home of one of the earliest and most influential Prime Ministers of Greece, Ioannis Kolettis, as well as the poets Krystallis and Zalacostas. Its 18th-century stone architecture alone is worth the hazardous trip. Though Vlach is still spoken, mostly by the old, both villages are strongly Greek in feeling, and have long been so. In Kalarites, the homes cling vertiginously to the steep mountain slope, the uppermost dwellings standing some 500 feet above the lowest, which are near the bottom of the mountain. If one has the time and the will to travel over such rugged mountains, the villages are worth visiting, if only because they offer yet another insight into the psyche and ethos of Vlach villages that are in several ways quite distinct.

The other Vlach villages in this region are not as difficult to reach as Syrakou and Kalarites, but many are still remote. Some of those I’ve visited — all of which are picturesque and hospitable, though not always proudly Vlach — are Matsuki, Haliki, Ambelochori, Amarandon, Krania-Kornu, Deshi, Chrisomilia, Kastania, Anthousa, Pirra, Neraidochori, Katafiton, Kamnai, Gardiki (large, with a hotel), and Pertouli (Winnifrith mentioned that German philologists found few willing to speak Vlach here; try the old man who runs the kiosk, a personable fellow who filled my ears with Vlach, but only after a half-hour in Greek, discreetly breaking the ice).

There are several approaches to the Vlach villages on the northern flanks of the Pindus Mountains. No doubt the best is by way of Ghrevena (Grebini) in Macedonia, and earthy and terribly dull town brimming with Pindus Vlachs. But from Metsovo (if you have a car) I suggest a more difficult but interesting route — my version of Frost’s “Road Not Taken.” The road from Metsovo to Ioannina runs right through Votonossi (Vutunoshi), a perpendicular Vlach village which serves as a sort of truck stop because of a couple of restaurants right off the road. Continuing on for many winding miles, there is a road turning east, with signs pointing toward Tristenon and Ghreveniti. According to Winnifrith, both were once Vlach villages, but no longer. I have traveled through them several times and found only one old couple in Ghreveniti, owners of the village’s only store, who spoke Vlach, but of course there may be more. There are few young people left in these two villages, and those interested in the Vlachs would do better by moving on, into the mountain hinterland, because ahead lie more obscure Vlach villages.

Back in Wace and Thompson’s day Makrini, Elatohori, Flambourari, and a couple of others were Vlach-speaking; in our time, Winnfrith commented on the reception he received when he spoke Vlach in Elatohori — a great deal of laughter and a little Vlach. He is right; on more than one occasion, people looked at me strangely when I spoke Vlach with them, as if I were a weird emissary from another time and place. Winnifrith also suspects that Vlach is better known in Flambourari than the people let on. Right again — I spoke it with several middle-aged men in this village, though they obviously do not use it regularly, perhaps only with the very old. These villages are all quaint and picturesque, but not at all tuned in to their Vlach roots; they represent another group of villages Hellenized beyond return.

Fortunately, though, if you keep going you’ll hit paydirt — of sorts. Less than an hour’s journey from Flambourari lies tiny Vouvousa (Baieasa), birthplace of this Newsletter’s very own Steven Tegu. It is Vlach, to be sure, and even if you stay only a few minutes, you will hear someone speaking it. Peaceful and quiet, Baieasa’s main attraction is the fact that there is little to do here except relax. There is a hotel right in the center of the village, right by the road that serves as the misohori. I’ve spent a few comfortable nights in its simple rooms, which look out onto one of the many Turkish pack-animal bridges found in Epirus. The Aous River flows right through Baieasa, and its thrashing stream provides a soothing backdrop for the peaceful sleep this village offers. The elderly Mr. Costa Perdiki owns the hotel (his wife Sotiria passed away just this year); the spartan restaurant offers roast lamb. In summer you are also likely to find hikers passing through — always a motley but hearty group of American, British, and European eccentrics who roam annually through the Pindus villages.

But keep going. An hour’s drive up the mountain from Baieasa is Perivoli, surely one of the Big Four among Vlach villages in Greece. I have spent much time there, and my friends and acquaintances in the village are many, including Ms. Papazisi-Papatheodorou. There is a large and comfortable hotel at the top of the village, owned by Lazaro Perdiki (cousin of Costa) and run by his daughter Angela. Say you’re from Bridgeport and someone in the village will know many of the same people you do, especially if you’re there for the festival of Sta Vinieri on June 26-28. Perivoli has the largest misohori in the Pindus Mountains, but it is not necessarily the prettiest village. It is large (4-500 families) and was once strongly Vlach. In many ways, compared to other villages, it still is, and the language is heard constantly. It seems almost everyone over 30 speaks it, but there are still many young ones who can and do, while others know almost nothing of it. One of the four villages practically canonized by Wace and Thompson, Perivoli’s future and the future of the Vlachs in Greece are inextricably intertwined.

One cannot talk about Perivoli without mentioning Avdhella, an hour’s walk away. Avdhella is the birthplace of several well-known figures in Vlach history, including the first Balkan cinematographers, the Manakia brothers, and the linguist Tache Papahagi. It is strongly pro-Vlach. Avdhella is outwardly more attractive than Perivoli, perhaps in times past it was more prosperous. But if so, it is no longer true, for today Perivoli prospers, while Avdhella is only a shadow of its past. A century and a half ago, many Avdhelliats settled in the region of Verria, where they have since prospered. It is a large and quiet village, and one notices immediately the far greater number of children in Perivoli. Even the language is heard more in Perivoli today.

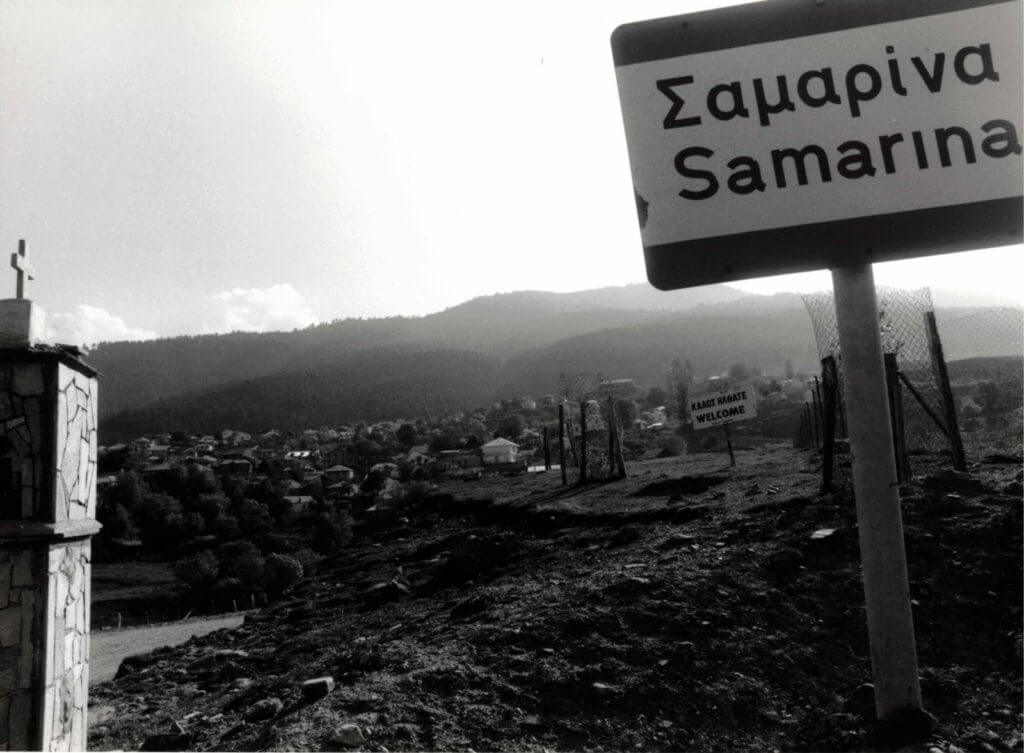

From Avdhella, over still more horrendous roads, lies Smixi, a very small but quaint Vlach village. Like so many others, it is featureless, good for an hour’s stop at most. But the road will take you to Samarina, easily the best-known Vlach village in the entire Balkan peninsula. Wace and Thompson based themselves in this large and attractive village, worked out a dictionary of its dialect, and essentially adopted it as their own. I’ve spent many weeks there, visiting it on every trip I make to Greece. Like most Vlach villages, it is extremely hospitable; but it is also perhaps too boastful about its legendary status in the Vlach world. There is lodging (a bit spartan) in Samarina, with a large hotel at the top of the village and smaller, cleaner places to stay around the misohori. And you won’t starve — there are enough restaurants and coffee shops.

The pride of the village is Sta Maria, the famous church with the pine tree growing on the roof (pictured in Wace and Thompson’s Nomads of the Balkans). It is tempting to write many pages about Samarina; it has a long, popular history, and the Samariniats are only too well aware of this. They consider themselves the only true Vlachs, guilty perhaps of the ancient Greek crime of hubris. Always strongly pro-Greek, Samarina still clings with pride to its Vlach legacy, though it probably still lives on its name.

The best time to visit Samarina is on the feast day of Sta Maria, August 15th. Most Greek villages celebrate their patron saint with great zeal, but you’ll see none like the celebration at Samarina, which goes on for several days, attracting Samariniats from throughout Greece, Europe, and even the United States. At night the cafes sizzle with music, food, and dancing, punctuated by the swooping sounds of clarinets resounding against the mountains — the festival evokes Vlach culture like no other. Also, among many other attractions, Samarina is the highest village in the Balkans, and even on summer nights you will need a jacket. But perhaps the village’s reputation has already piqued your interest: Vlach villages have always slandered and poked fun at each other, each claiming some unfounded superiority over the others, and in Vlach circles the Samariniats have long been derided as skilled liars — a reputation the Smariniats actually seem to enjoy. Whatever the case — and not to belittle any other village — but Samarina remains for me the prototypical Vlach village. You’ll find its inhabitants an impressive, but wily lot.

I have always felt challenged to follow some of the old paths marked by Wace and Thompson in their travels. Early one morning, with a shepherd’s crook (carlig) in hand, I took off on the three-hour walk from Samarina to Furka, another old Vlach village. The crook made me feel more secure, for walking in the Pindus Mountains, you will surely be attacked by starving, vicious sheep dogs. Different people have different advice as to how to get the dogs to back off, from throwing rocks at them and chasing them, to merely sitting right down on the spot; you will have to find your own method. Sheep dogs notwithstanding, the walk to Furka is an exhilarating, peaceful experience, with nothing around you but snow-capped peaks (even in early July) and the sound of your own footsteps breaking the otherwise total silence. I saw a couple of eagles flying overhead, part of the scenery of places like this. From a distance, Furka looks empty, a rubble of stone, and when you get there, it’s not much more. Like its counterparts, Furka has seen better days, and even in summer only a handful of families return. There are even a few Farsherot families living there now, though originally it was not a Farsherot village. Oddly enough, the first person I met there was an old Fukiat, Dimitris Ziozis, who was visiting his village from Flushing, New York! He said he was planning to stay, after 50 years in New York. There are no accommodations in Furka, but a stroll through it reveals the beauty of its abandoned homes. You sense there is a great local history in this village, so splendid in its isolation. As I have done in too many other Vlach villages, I wondered where all the people had gone, and why they had left such peaceful beauty. Economics? The idea of purchasing an abandoned home here (from whom?) stayed in my mind over the three-hour walk back to Samarina. The idea is still in my mind — Furka is so charming!

Since our villages lie off the beaten track, you might try the back road out of Samarina, which passes through four Vlach villages on its way heading north toward the town of Konitsa and on to Albania: Armata, a very small, friendly village of perhaps 100 houses, which was struggling even in Wace and Thompson’s time — it is resilient and still inhabited; Dhistrato (Briaza), where I found Vlach so strong that little children spoke it; pades (Padz); and Palioseli. Wace and Thompson noted that the last two villages were eager to prove their Hellenic origin to visitors, but they have always been pure Vlach villages, and today one still hears the language spoken. Once past Palioseli there is only a Greek village to pass through before descending into the town of Konitsa, which clings to the lip of the northern flanks of the Pindus. Before you lies a vista of Albania’s rugged mountains.

Before describing some unusual villages in the Pogoni region of Epirus, let me mention three Vlach villages reached only from the Konitsa road toward Ioannina and the villages of Zagori: Laista (Laka), Vrisohori (Leshnitsa), and Iliohori (Dobrinovo). Wace and Thompson said that Laka, “if asked, would declare itself to be of pure Hellenic stock, but in private all its inhabitants talk Vlach glibly.” I’ve visited this village twice (the first time through the mud of a torrential downpour), and though Vlach is not quite dead yet, the writing is on the wall — some of the young can still understand a little, but I met only a few able to speak it, and that rather hesitantly. It is a beautiful and remote village (one terrible road in, the same road out), but clearly on the verge of discarding its ethnic heritage. Yet for all its sense of abandonment, Laka flourishes next to Iliohori and Vrisohori, where I met a relative of Michael Dukakis. A retired schoolteacher, he related to me the history of both the village and the Boukis family (maiden name of Dukakis’s mother Euterpe) in Greek — he said, incongruously, that his Vlach was limited, which I found difficult to believe of a 70-year-old man who had grown up in a once-prospering Vlach village. But I fear that both villages, once completely Vlach-speaking, may be left behind soon. What a pity — such a gorgeous place!

A final word about the Zagori: This is a remarkable corner of Greece, a trove of amazing architectural treasures. The 42 villages of the Zagori are officially designated by the Greek government as “historic settlements.” Largely depopulated now, but still hauntingly beautiful, they reflect the proud history of Epirus. There are only a few Vlachs in these villages, but many Sarakatsans, who have recently given up their nomadic, transhumant way of life. If you put your Vlach itinerary aside, this may be the most lovely region Greece has to offer. Its handsome villages, all located near the spectacular Vikos Gorge, include Aristi, Tsepelovo, Vradeto, Skamneli, Monodendri (a remarkable place!), Vitsa, Papingo (two villages), and Kakkouli.

It is time to straddle the Albanian border. North of Ioannina, in the region of Epirus called Pogoni, there are paved roads which lead into some peculiar places. One is Doliana (there are several villages by that name in Greece), which is home to Greeks, Slbanians, Gypsies, and Vlachs. Though the Vlachs are not numerous, they occupy the upper part of the village. And, like all the Vlachs in Pogoni, they call themselves Remen, with origins in Albania. There are more in nearby Visani, and though it is not entirely Vlach, one can still hear the language spoken. Edging even closer to Albania, Delvinaki is a large village, probably 40 percent Vlach. It is the home of the Halkias family, well-known Epirot musicians (Pericles, his son Petros, and Petros’s son Babis, follow each other as sixth- or seventh-generation clarinetists in the family). There are also many Vlach-speaking Gypsies in the village (as there are also at Metsovo). It is a prosperous village, as are many others in this area, and there is one obvious clue as to the source of the prosperity: German license plates. Many Greeks and Vlachs from Epirus, and especially from Pogoni, live and work in Germany, returning to their villages in the summer.

Parakalamos, near Delvinaki, is a village of Gypsy musicians, several of whom can hold their own in Vlach. But just east of Delvinaki, past Vasiliko (birthplace of the late Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras), stands Kephalovriso, better known among Vlachs as Migideia. You won’t find this village on any travel guides pointing out Vlach centers such as Metsovo or Samarina. Wace and Thompson, surprisingly, knew nothing of it, or it somehow escaped mention in their book, and Winnifrith’s only contact with it was through a waiter in Corfu, who said he spoke Vlach at home in this village. He wasn’t kidding. Kephalovriso is an entirely Albanian Vlach village, and even today there are a few five-year-olds who master Greek only once they’re in school. In most houses, Vlach is still the dominant language. Only a couple of miles from the Albanian border, Kephalovriso is easy to reach. And yet, surely it is one of the most obscure and least-visited of all Vlach villages. No one seems to know about it, and, frankly, Kephalovriso seems to stand alone, embracing Pogoni and Epirus rather than the Vlachs, and unobtrusively speaking its old vernacular in the home (along with Greek) and, evidently, making no big thing of it. It is, by the way, the same Migideia of song, bombarded by German planes during World War II.

There are no Vlach villages in Thesprotia, the region of northwestern Greece, except for an extremely obscure place called Morfion, near the seaside resort of Parga. I stumbled upon the village by accident. It is small, not very modern, and made up of Farsherots not long settled from nomadic life (in fact, traveling somewhere in the Pindus I met a family from Morfion in their summer pastures). In the bustling port city of Igoumenitsa, which features ferries to Corfu and Italy, there are now many settled Farsherots working in hotels and other businesses. But the region is filled with ethnic Albanians.

We somehow tend to think that most villages in northern Greece are Vlach; this is a naive and absurd claim. Anyone who has read Nicholas Gage’s book Eleni might entertain the notion that Lia (accent on the “a”) is a Vlach village — it is not, nor are the villages around it. I have been there twice, meeting Mr. Gage on one of those trips. It is high up in the Mourgani Mountains, right on the Albanian border, and Mr. Gage has built a lovely hotel in the village and named it after his mother. It is interesting, mainly as a relic of the bloody Greek Civil War, as are neighboring Babouri, Vitsa, and Tsamantas.

Way up in Greek Macedonia, not too far from the Albanian border, lies the lovely lake town of Kastoria, known for its furriers. There are many Vlachs in the town, all from neighboring mountain villages. One, Ieropigi, is Farsherot — Vlach is still spoken there, as it is in the larger village of Agios Orestikon (Belkamen), just south of Kastoria. Ieropigi is a curious stop on the Vlach itinerary, deserving of a closer look. Zoe Papazisi-Papatheodorou learned some old Vlach folk-songs in the village. North of Kastoria, right on the border, there are two small but interesting Vlach villages, one practically abandoned, and the other clearly moribund. A few miles from the Albanian border is Vatohori (Breshnitsa), once a well-known Farsherot village. It is now practically a ghost town, with only a few families left, half of whom are Macedonian Slavs. In fact, there are many abandoned villages in this area of Macedonia — I’ve walked through several of them, feeling as if I were being watched, though I was the only person in the village, the only living thing, in fact, aside from a stray goat here and there. Vatohori, a very eerie place today, reeks of history, but now its Vlachs are scattered everywhere, their native village long forgotten. I recall leaving it and heading north, the Albanian mountains rising menacingly before me. Travelffig alone on the winding road, I grew concerned with each new “Forbidden Zone” sign I passed, thinking I might have inadvertently entered Albania. But Kristallopigi lay ahead, and I was determined to see it, nestled as it is only a few hundred yards from Albania, not too far from Bilishti. For one accustomed to prosperous places like Metsovo and Samarina, Kristallopigi abruptly brings you down to earth. It is one of the poorest Vlach villages in Greece (a rarity, in fact). In my two visits there some young children spoke Vlach as we walked toward the Albanian border; they didn’t seem too thrilled about it, and their older brothers and sisters spoke it better. This village will have a tough time keeping its young people there.

In Greek Macedonia there are almost certainly more Macedonian Slavs than Vlachs, though the Greek government relentlessly insists that there are not many of either. I have walked through more than one village where, in addition to Greek, that strange language was spoken. It is thus only natural that in the large town of Florina, there are Slavs, Greeks, Albanians, and Vlachs. But there are also a few more obscure Vlach villages beyond it. Pisoderi was once a prospering Farsherot village, but almost everyone has packed up and left. There is a new ski resort there, meant to bring in tourist dollars, not Vlachs; as a Vlach village, no prayers can save it; it has a much better chance of surviving as an alpine ski resort. South of Florina is Drosopigi, which also contains ethnic Albanians. A couple of miles north of Pisoderi, in an area that just does not seem like Greece, Winnifrith fell upon Kallithea and Aghios Germanos. I had never heard of these villages until his book came out and so, naturally, had to visit them. There are some Pontic Greeks there, as well as Vlachs, who to me seemed like anything but Vlachs. Not only are both places culturally impoverished, but they are economically poor as well, malting even Kristallopigi look wealthy. Many of the houses were in semi-ruin and both villages were cool to me and my brother Gus. (Perhaps if we had stayed longer, we would have felt differently.) People stared at us strangely when we spoke Vlach, and it felt good to take the road heading west out of the villages and into a little-known and rarely visited area, that little comer of Greek Macedonia tucked away and surrounded by Albania on one side and Lake Prespa on the other. Once again, Winnifrith filled me in on two outlandishly obscure Vlach villages, Pili and Vronderon. Both are small, but still Vlach to this day, though Vronderon seemed to have a healthier atmosphere. Check a map and you’ll see their odd location, much closer to Albania than to mainland Greece.

We tend to overlook the fact that the obscure Vlach villages in Greece outnumber the well-known ones. Pleasa was as obscure as any I’ve previously mentioned; it was brought to significance only because its descendants eventually abandoned it and settled in America, Romania, and Greece. It had a local history, just like all of these villages, but its grinding poverty, old way of life, and sense of a hopeless future ultimately drove everyone out. It seems, however, that these little-known villages stand at the heart of the Vlach experience in the Balkans, that obscure villages parallel the obscure identity of the Vlachs, and that in a way these settlements, always struggling, best typify the Vlach dilemma for ethnic survival within larger, more vibrant societies. Simply put: some make it, and some don’t. It is relatively easy for places like Metsovo or Perivoh to hang on to a Vlach ethos; just the opposite is true for these run-down, downtrodden places. Which makes me think of Sisanion, a Vlach village in Macedonia in which no Vlach-speakers are left. Or Blatsa, which was Hellenizing itself in Wace and Thompson’s time. And especially Siatista, a prospering Greek town in Macedonia once comprised almost entirely of Samariniats. They haven’t left — their descendants are still there, only today, you won’t find even an old man or old woman who can speak it; even worse, you won’t find one who will tell you he or she is from an old Vlach family.

Halfway between Florina and Kozani, still in Macedonia, there are two large Vlach villages which need little introduction. There is nothing obscure about them; their histories actually rival those of Samarina and Metsovo. Klissoura is a large Vlach village whose history includes strife and bloodshed as well as prosperity and a Romanian school. The Germans laid siege to it, and so did the Bulgarians; 250 women and children were massacred there in 1944. There are a couple of hotels in the village, and Vlach is spoken by practically everyone over 30; in my time there I saw no efforts by the young to rescue the language but, paradoxically, as Winnifrith pointed out, there is a tangible interest in its Vlach culture, which means there are still some real possibilities here. Klissoura would be an interesting place to observe over the next ten years; it is low- key but proud, conscious of its legacy.

East of Klissoura, and higher up, is a Vlach village of another kind. Nimfaion (Neveska), pictured in Wace and Thompson’s book, is still in pretty good shape as Vlach villages go. I spent a couple of nights in one of the village’s two hotels, and not finding a ride out of the village, was forced to walk a few winding miles down the mountain to Aetos, the nearest town, and inadvertently I wound up in someone’s back yard, where people were speaking Slavic. Nimfaion’s history gives you a pretty good idea of the diversity of the Vlachs, of their range in the Balkans, how they’ve scattered and settled and, in particular, how they’ve prospered everywhere. Nimfaion is large, clean, and attractive, but you get the idea that the Vlachs come here to rest and to meet again, after prospering in businesses all over northern Greece, especially in Thessaloniki. Shepherding never really took hold in this village; settled largely by refugees from Moscopolis after its second sacking at the end of the 18th century, Nimfaion’s Vlachs have flourished as merchants — an obvious continuity from the commercial Moscopolis of earlier generations. Its history is replete with wealthy merchants settled in Austria, Italy, Switzerland, Egypt, Germany, and Serbia, and though assimilation into those societies has stripped the village down to a more locally-minded core, Vlach still survives (despite a strong Greek sentiment). It was here one day, while sitting at a cafe reading Nacu Zdru’s Frandza Viaha, that a gentleman of the village, perhaps in his 60s, accosted me for my seeming act of defiance (reading Vlach publications offends many Greek Vlachs, a testament to the extreme sensitivity of this issue). But, as has always been my experience in Greece, we had coffee together, despite our disagreement, and we talked. Most fervent pro-Greek Vlachs are not so much pro-Greek as they are against any connection with Romania. For most, as with this gentleman, it is okay to speak Vlach, as long as you do not obstinately insist upon it, you are careful not to deny their Hellenism, and — especially – you are prudent enough to let Vlach be Vlach and not Romanian. This is true not just in Nimfaion, but in practically every village I have visited.

Coming almost full circle around central and northern Greece, the three large towns of Edessa, Naoussa, and Verria contain many Vlachs. Those around Edessa are mostly Farsherots from once-strongly-Romanian villages like Ano Grammatiko (Grammaticuva), Patima (Patichina, now abandoned), and Kendrona (Candruva). They are all moribund today, largely because of their former alliance with Romania; many of the inhabitants, who suffered terribly at the hands of Greeks for being Vlachs, left for Romania.

The opposite is true of the Pindus Vlachs long settled around Verria and Naoussa. For the most part Samariniats and Avdhelliats, residents of the two towns boast strong Vlach societies, with many young people still fluent in the language. Oddly enough, while interest in the Vlachs is high in the two towns, some of the Vlach mountain villages around them are mere shadows of their former selves. Seli (Selia) was once a Farsherot settlement but today houses only a ski lodge. Its only significance these days is as the usual site for the annual gathering of the Pan-Hellenic Union of Vlach Cultural Societies. The lower village, still Vlach, is Kato Vermion. Higher up, on a very winding, paved road, lies Xirolivadho, which is faltering culturally as a Vlach village but prospering economically with money made in the towns below.

Heading toward Thessaloniki, in the flat hinterland between Edessa and Giannitsa, there is a town called Kria Vrisi. There are many Farsherots in the town, old Pleashiot families long settled there, most of whom still speak Vlach volubly. This town is interesting in that it offers a more recent perspective into the assimilation process.

Three years ago, with a rented car, we toured the Meglen Vlach villages on the Yugoslavian border, north of Thessaloniki. Wace and Thompson knew these villages well, as does Winnifrith today. And of course they were right about one thing: the Meglen Vlachs are different, not only in language but in attitudes and traditions. At first, my brother Gus and I found Meglen Vlach practically unintelligible – it is an amalgam of Vlach, Romanian, and Slavic, and it takes a while for your ear to get accustomed to the inflection and syntax (not to mention the vocabulary) before comprehension begins. After so many “regular” Vlachs, the Meglenites and their villages were a refreshing contrast. We were lured to Skra in particular, because Winnifrith had not been welcomed there; we felt challenged to penetrate the village’s defenses and find out why Winnifrith had been tamed away. By speaking Greek to the shopkeeper in the misohori, but conversing discreetly with my brother in Vlach, I managed to make our arrival subtle and unthreatening, and we were welcomed. We did not enter with questions about the Vlachs, nor did we see any sense in approaching strangers in the village in Vlach, which seems anyway a bit too personal. It was their village, their territory, their “space,” and as obvious intruders in a village not at all accustomed to seeing strangers, it behooved us to approach with restraint and caution. And we were rewarded for it — we had a hard time leaving this friendly village tucked away in the low hills on the Yugoslav border. The shopkeeper, Karakostandinos Armonios, insisted we stay longer, but we were eager to move on to the next village, Archangelos.

In Wace and Tompson’s day, this place was called Oshani, and today it is the largest and most prosperous of the Meglen villages. But here, too, we had to break the ice subtly as Vlach-speaking strangers before we could settle into friendly conversation. We found Skra’s atmosphere more cozy. We only visited three other Meglen villages nearby, Pericleia, Koupa, and Notia, which was once a Muslim village and later converted back to Christianity. In fact, there are probably more Pontic Greeks in the village than Vlachs. Our last village in this district was not Meglen but “regular” Vlach, probably with roots in Albania. Megali Livadhia is vastly different from its neighboring villages – you’ll have few or no dialectal problems here.

You will leave these villages with at least two distinct impressions: the Meglen Vlachs won’t seem like Vlachs to you — they are different, and the feeling of a common bond, often tangible in other Vlach villages, may be missing here (I found this exhilarating). In the same light, these villages help forge an awareness of the great diversity among the Vlachs. Any isolated Vlach community — especially ours in America — is vulnerable to cultural myopia and superciliousness; we are all burdened with the attitude that we are superior to other people, including other Vlachs. A greater awareness of the diversity of our people, which includes groups that are neither linked nor interested in linking with other Vlachs, can be a humbling experience. Indeed, who is to say who are the “real” Vlachs and who are not?

The circle is nearly complete. South of Thessaloniki, into Thessaly, perched on fabled Mt. Olympus, two villages, Kokkinoplo and Livadhi, remain, while a third, Fteri, though still standing, is abandoned. Fteri was populated in Wace and Thompson’s days, left for dead by the time Winnifrith arrived, and it’s not likely to be reborn any time soon, though the idea is plausible. Kokkinoplo is purely Vlach but hardly exhilarating; it has seen better days. You’ll still hear the language, spoken there with a sort of lisp. But this is not a village in which to linger, unless you have a reason. Instead, the place to see in this area is Livadhi, higher up than Kokkinoplo, and large and prosperous. It seems, along with Metsovo, to be among the richest Vlach villages in Greece. First glimpsed around a hairpin turn in the mountain road, Livadhi seems to jump out at you; it is a cluster of finely built stone homes, perched on the side of the mountain. There are hotels and restaurants, and on summer evenings, the place is booming. You’ll hear Vlach spoken by young and old. I met an elderly couple here who have resided in Athens for 50 years, but faithfully spend two months every summer in their village. And on the island of Skiathos, I ate at a thriving beach restaurant owned by a Livadhi family. When they found out I was Vlach, they would not let me pay. Livadhi might have something positive to say to all of us about the future of the Vlachs…

It is time to call a halt to these travels and put this article to rest. It is likely only a handful will find any interest or meaning in reading about Vlach villages; they are far too remote from our everyday lives to hold much significance. But when we take a look at villages which were once Vlach, where the language has completely vanished, where even 80-year-old women have forgotten it, or speak only a word or two, we know there is a hidden history. And because some have already paved the road for us, and scholars are now gathering ’round the campfire to discuss this most unusual and threatened ethnic group, perhaps it is fitting that our isolated community also take a look, with freshness and objectivity, at the diverse Vlach experience, so much of which has never been told.

Hello, my father’s name was Xristos Vlahos. He lived is Lemnos. I was told that he grandfather migrated there from Turky. I now live in New York and I have recently become interested in my Vlach heritage.

Dear Aristea, I am very sorry for the delay in replying, your note ended up in the wrong folder on this end. We would be happy to help you in your desire to learn more about the Vlachs. There is a lot of information on the web site, and members have the added benefit of being able to participate in forums where ancestry and genealogy can be discussed. Let me know what we can do — thanks! –Nick Balamaci