The Panagire, as It Was Celebrated in Baiesa

The grand social event in Baieasa, as in all Vlach villages, was the panagire, on the day of the Assumption, celebrated beginning on August 15th of each year. This was a celebration involving much pomp and color that lasted several days and preparations for it began months ahead. The house was scrubbed clean, food and goodies cooked and the clothes made ready. It was during the panagire that everyone would wear their very best. The Vlach women, with their agile fingers, would embroider traditional designs on their apparel, especially the aprons.

This was one festivity that everyone wanted to celebrate. Whenever a Vlach was far away from home, in some foreign country, he would dream of being in his home town celebrating the panagire. We might compare this to the American longing to be home for Christmas. The panagire was one celebration that no one wanted to miss. Even the word panagire evokes joy in the heart of a Vlach.

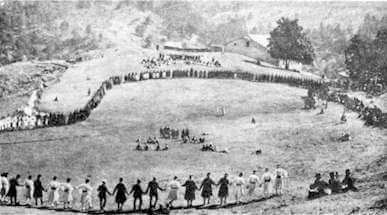

The dances were celebrated near the church or in the meadows. There would be two circles of dancers, one composed of men and the other of women. There were Gypsy musicians, usually a fiddler, a clarinet player, a tambourine player, and the lute player. To me, then a child, the lute player appeared as the most fascinating of the group. It is curious to note that the children were not encouraged to play instruments. In fact, it was discouraged because being a musician was the profession of Gypsies and, unfortunately, “Gypsy” in the Aromanian language is synonymous with “beggar.” An uncle of mine told me that he, as a young man, had made a lute and was beginning to learn how to play it. This was done secretly, with the lute hidden. It was discovered by his father who smashed it, saying that playing an instrument was shameful, practiced only by “beggars.”

The beauty of the lute fascinated me. It is a pear-shaped instrument made of several kinds of wood, highly polished, forming its sound box or belly. The dark-skinned musician with a bushy mustache would work his bony fingers over the frets. To me it seemed that this mysterious instrument with its equally mysterious player was telling a story of long ago, a sad story that could not be told in words. It was a monotonous, haunting music. Even when the music was supposed to be happy, there was a faint echo, an undertone of melancholy and tragedy. And it was natural to believe that it was so, because all the people of Baieasa had lived for centuries in a harsh and hostile environment marked by battles with the Turks and by brigands, famines, and floods and countless other hardships.

The dancing, which began after the religious ceremonies in the church, would last all day. The dancers, holding each other by the hand, circled the meadow to the rhythm of the Gypsy music. After each round of music, the leaders of the two circles would change. Those not dancing watched from the sidelines.

The grand moment in one’s life was to lead the dance–you waited an entire year for this moment! Every eye in the village was focused on you. Your chest swelled with pride, though you were perhaps a bit nervous as you waited for the first beat of the music. The person next to you acted as a kind of second. He was generally your best friend, attached to you by a handkerchief held in the hand, and he transmitted his energy to you to animate you, just as the Spaniards animate a dancer by shouting “Ole!” Even the people watching the dance played a role at this crucial moment. Your good friend (or friends watching from the sidelines) would intervene at the proper moment: He would walk up to the chief musician and make sure that while you were leading the dance, he would play like he never played before. He did this by taking a bill of large denomination from his pocket, wetting it with his tongue and sticking it on the musician’s forehead. Sometimes the musician’s face would be almost invisible, covered with money. This is indeed a strange custom; I have seen it repeated in some Arabic countries in North Africa, and I believe that it was brought to Greece by the Turks.

And so, with the encouragement from your friend who held you by the hand through a handkerchief, together with the stimulation of the chief musician through the big money stuck on his forehead, you danced like you never danced before, leaping into the air Zorba-style, defying gravity and everything that held you earthbound. It was a moment of great pride, joy, and ecstasy.

If you were a man, your dance would be an expression of your masculinity, of being a macho, a palikari. To be a palikari was the aspiration of every man! If you were a single woman, your grace, beauty, and poise would surely be noticed by some joni (palikari) who might consider you his future nevasta, or bride.

As the leading dancer you personified the joy of living. It was a brave challenge to the entire world.

Responses