Preserving Aromanian (Vlach)

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This article is a reflection of many journeys taken to dozens of Vlach villages in Thessaly, Epirus, and Macedonia. It is not concerned with Vlach origins or history, but solely with the preservation of an endangered two-thousand year old language. Nor does it attempt to discuss any political conflicts in which the Greek Vlachs have been sporadically embroiled. Their record of patriotism to the Greek nation is unassailable.

The Vlachs are most numerous in northern Greece, but large communities live in Albania, FYROM (the only place where they are recognized as a distinct ethnic group), and Romania, while in Serbia a large proportion of its once significant Vlach population has long been assimilated. Consequently, there are a great many more individuals of Vlach ancestry in Greece and the Balkans than might be surmised, as thousands over the centuries have lost both their language and knowledge of their ancestry. Through the Internet, however, and a fledgling school here and there, one still finds individuals and the occasional cultural society determined to preserve their ancient language. It will be the responsibility of the younger generations of these various Vlach communities to resourcefully preserve their linguistic heritage if it is to survive.

* * *

“Prepi na milate Ellinika!” (You must speak Greek!) Mr. Evangelos Averoff-Tossitsa asserted with a scolding finger the day we met in Metsovo, shortly before his death. Greece’s former Minister of Defense, on a political visit to his prosperous mountain village in Epirus, would hear nothing of the greetings I offered in the Vlach (Aromanian) language, and insisted on Greek, even while Vlach was spoken all around us. The admonishment, a shock to me at the time in Metsovo, was in fact my first encounter with “unofficial” opposition to the Vlach language in Greece.

I had questions later that evening for an audience of sympathetic old timers gathered in the village’s large and colorful misohori. Why did Mr. Averoff, a polyglot, berate me for speaking in the first language we both had ever heard, and in Metsovo, of all places? And why the admonishment to this stranger from America speaking in the native language of this storied Pindus Mountain village, as well as in scores of other villages on Pindus? Later that day I stood by perplexed as he conversed glibly in Vlach with a handful of village elders. This, then, became a recurrent theme in my annual journeys to over 80 of Greece’s Vlach villages (Vlahohoria) on Pindus, Grammos, and Olympos, as well as other districts where Vlachs live: why were some people so bitterly opposed to their 2,000 year old ancestral language, so insistent on speaking only Greek in entirely Vlach villages? And what does this portend for the future of a language clinging to its twelfth hour, with little hope of survival? The answers came much later.

The Vlach-Aromanian language, spoken in Greece, Albania, FYROM, and Romania, is fading rapidly, and to many young people their ancestral language is archaic, unfit for modern life. Yet, ironically, it is their Latin language, in all its antiquity, that has always set them apart, and while there are more speakers of it than Chamicuro, an Indian language of Peru, Vlach (officially, Aromanian) has unceremoniously gained entry into The Unesco Red Book on Endangered Languages of Europe. There should be concern here: in a frenetically multicultural world it is ironic that philologists track down any language or dialect’s last speakers; moreover, they warn that perhaps half of the six thousand or so spoken worldwide will die off by middle of the century.

The subject of Vlachs and minorities can touch a raw nerve in Greece. But there is no political agenda in this article. I do not proclaim the Vlachs as belonging to this group or that, a practice common, if not urgent, in the Balkans. Nor do I attempt to speak for the Vlachs of Greece, an absurd notion. Inspired instead by the journeys of the iconic Patrick Leigh Fermor (always one with a sharp eye for Greece’s “strange” communities) and even more by pure wanderlust, my numerous excursions to their mountain enclaves in Thessaly, Epirus, and Macedonia are treks that most Greek Vlachs themselves have not made, and would not consider. And there is something else: though the Vlachs are a dynamic segment of the country’s central and northern population, and have contributed much to Greece, politically, culturally, and economically, that dynamism does not translate into its own linguistic preservation.

Mr. Fermor’s keen eye for the Greek world’s “strange” communities belies recent government notions about minorities existing on its own soil, excluding the Turks of Thrace and the ubiquitous Roma (Gypsy) communities. But in the Balkans there is nothing if not diversity, and it is naive to assume Greece alone is free of any kind of minority. How, one might fairly ask, can just one country in the Balkan tinderbox, dangerously tense with ethnics, manage to free itself of any other communities, ethnic, linguistic, or otherwise? For the Greek Vlachs, however, patriotism has never been a question.

“Noi himu Grets” (We are Greeks), as one robust old man from Volos’s Vlach quarter (Aghia Paraskevi) sternly reminded me one day in the native tongue. Rarely have they made political demands (most of those who did ended up migrating to Romania), rarely are they anything other than patriotic Greek citizens. Most Greek Vlachs, if asked, and I have asked hundreds, in no way consider themselves a minority, raising then interesting questions about assimilation and language loss. Just how does one assimilate if one is not a minority, if one lives on the ancestral soil and is the most ardent Greek patriot? These are viable questions to examine, but the Vlachs, because of their language, can best answer those themselves. Even the most fervent whom I’ve met, those with the strongest anti-Romanian sentiments (as is the case with most Greek Vlachs), exuded a tangible “distinctiveness,” due, without question, to a separate language (and thus, as one Athenian scholar suggested to me, “their own history”), and while their Greek patriotism is unassailable, many still cling with affection to an identity all their own. In their many picturesque villages that sprinkle the mountains of northern Greece one senses the idea of a community more palpable than even that of the once-nomadic Sarakatsans (only Greek-speaking), and I have met middle-aged Vlachs who recalled mothers and grandmothers whose Greek was rudimentary at best. One needs only a short stay in a Vlach village to sense, even if vaguely, a separate ethos, a distinct notion of linguistic and, frequently, cultural identity, irrespective of their strong Greek nationalistic feelings. “D’anostru iasti” (dhiko mas einai, in Greek: “one of our own”), as I’ve heard so many times, where the Vlach language broke the ice in an unfamiliar village, opening doors to enormous hospitality and friendship, and in one, even to a wedding about to start. As well, one cannot forget that for centuries, they, like other former nomadic and semi-nomadic groups worldwide, scorned marriage to “outsiders,” or even to Vlachs from different villages, living instead in their own hierarchical world based on dialect or group. Barely two generations ago, in their once highly endogamous society, a Vlach marrying a Greek, or Albanian, or even Vlachs from outside their own group (especially in villages), often faced ridicule, and, as has happened, become the subject of derisive song, and most Vlachs know at least one. So it matters little today if the Greek Vlachs do not consider themselves a minority; their undeniably distinctive identity is their language, and assimilation then takes on no uncertain meaning: the threat to a language, and the heritage which spawned it, and one simply cannot negate the Vlachs’ own language. One friend from the Pindus Mountains, the Vlach patridha (fatherland), proudly told me one day in the old language, “Io hiu multu Armanu, sh multu Greku, ama a casa mash Vlaheshti zburamu” (I am very Vlach and very Greek, but at home we only speak Vlach).

It is impossible today to determine just how many Vlachs reside in Greece and the Balkans, though Greece by far can claim the largest number, followed by Albania and Romania. A census is absurd, as there would be few willing participants, while assimilation, or an abandoned Vlach language and identity, have for centuries decreased their numbers. Perhaps at this point in their long history the only telling statistic might be the number of fairly fluent language users, and I’ve heard numbers vary from as low as 30,000 to a couple hundred thousand (probably too high a figure). Through marriage with non-Vlachs, movement away from mountain villages to towns and cities, and the disfavor of the language among the young, many thousands lost it generations ago. Still, one fact emerges: no matter the number of speakers, a high percentage of them are over forty, painting a potentially dismal picture for the language’s future.

Who, then, are the Vlachs, and just what are their origins? These questions have puzzled historians for centuries, but politically this is a highly debatable, and flammable, topic, and one far beyond the scope of this article. Yet the questions remain: are they after all Latinized Greeks, isolated remnants of the vast Roman Empire, clinging oddly, and stubbornly, to a rustic Latin language these past 2,000 years? Can they be a scattered Romanian minority living in the diaspora, separated for centuries from their Dacian homeland to the east? Or can they claim a number of indigenous ancestors from the dustbins of misty Balkan history? And why, some ask, are they found all over the Balkans, yet have never had a nation of their own? Short of conclusive scientific evidence, there are many theories, some of them outlandish, and almost all of them nationalistic. But prior to the 1970s, when these studies suddenly gathered momentum and provided fuel for controversy, many historians with no political axe to grind theorized them as the Latinized descendants of autochthonous Balkan tribes, chief among them Thracians, Macedonian and Illyrians, and their languages and dialects have survived to this day, albeit tenuously, in their villages in the Balkan mountains. This is delicate ground, and one must run the gauntlet of fiery nationalists on several sides claiming the Vlachs as their own. With so much uncertainty, perhaps the only certainties are these: the Vlachs speak a Latin-based language, preserved through the millennia in their mountain homes, with similarities to Romanian, and is fast losing ground, especially among the young; Vlachs are scattered over several Balkan countries, and were once more numerous, but have largely assimilated into these populations; in these countries many played important roles in politics, the professions, and the arts, which is contrary to the perceived notion as exclusively shepherds; and today, some still resist complete assimilation, clinging to their mother tongue with nostalgic affection, in spite of the difficult odds of preserving it.

Most Vlachs today regard themselves as Greeks, Albanians, or Romanians, or to some a Romanian minority with a unique linguistic inheritance. But I’ve met an anomalous few, who, quite privately for that matter, believe that Vlachs are simply Vlachs, romantically citing the unlikely survival of their language from Balkan Latinity as evidence of a cultural milieu they proudly call their own.

But in the Balkans ethnicity is serious business, and today the prevailing notion in Greece claims them as nothing more than Greeks who inherited their provincial Latin from Roman soldiers who married local Greek women, and they’ve been speaking it ever since, to this day miraculously preserved in the crystalline air of their high mountain villages. It’s an interesting notion, believed unequivocally my most Greek Vlachs, but according to Tom Winnifrith, a British scholar and the author of two books on the Vlachs, this theory contradicts one significant linguistic reality: children everywhere learn languages at the knees of their mothers and grandmothers, rarely their fathers, and in the ancient theater of Greek-speaking mothers and Latin-speaking fathers, the Vlach language would almost certainly have vanished long, long ago. Pindus villages like Perivoli and Avdhela, and the famous Samarina, Greece’s highest-elevation village, along with Gardiki and Livadhi in Thessaly, Klissoura and Nymphaion in Macedonia, and Syrako, Kalarites (ancestral village of the Bulgari jewelry clan) and Kephalovrisso, in Epirus, would have ceased to know Vlach centuries ago; moreover, it is unlikely today they would even have recollection that they were once Vlach-speaking, as has happened to a number of villages.

Not surprisingly, less than two decades ago one could still find a handful of monoglot old women who never learned Greek (even more in previous generations), clinging to the comfort of their own language in lives lived almost exclusively in their mountain villages. I had encountered several in my travels, most in the Pindus Mountains (one whose sons I later met in Astoria, New York), hardy old ladies clad head to toe in black wool who, living all their lives in Greece, would have struggled with their broken Greek in Athens. I even sat with one on a bus leaving the capitol, heading home to her Pindus village after visiting a son in the city, and more than one head turned our way along the journey. Were they Vlachs listening in, or just curious Greeks? And I met another, incongruously, in the Vlach community of Bridgeport, Connecticut, the matriarch of a family from the Olympus village of Kokkinoplo. Apologizing for her passable Greek, she preferred instead the ancient vernacular of her village on the slopes of Mount Olympus. Those old Vlach ladies, relics of another time, are gone now, their kind not to be seen again even in the most remote mountain village. But I had also encountered other old ladies whose villages were being Hellenized many, many decades ago, who remembered nothing of the language they faintly recalled hearing from their grandparents, though with a hint of nostalgia, and much prompting on my part, delighted in a recovered word here or there.

Threatened as Vlach is, and evidence of that threat is abundant, some villages preserve it better than others, though the young, if they know it, tend to reserve it for the elderly. Still others use it resourcefully as a language of secrecy. Stigmatized by the word Vlachos, there are many young people embarrassed by the language of their grandparents’ generation, and I vividly recall teenagers astonished to hear this traveler from America conversing, anachronistically, with the old folks of their villages. A few even resorted to derisive laughter, in utter disbelief that someone from modern America should speak such an impractical and moribund language, and I found it disquieting that they had neither regard nor respect for even the history of their ancestral language. These young folks aside, their language, a bizarre survival from Roman times (and not a rustic northern Greek dialect), has stubbornly held its ground these past 2,000 years, though by all estimates it should have perished long ago. Never officially written, never taught in schools (aside from some short-lived attempts), never encouraged anywhere, its existence today is all the more improbable. But politics played its part. From the second half of the nineteenth century until the 1940s, the Romanian government – anxious and eager to claim the Vlachs as their own, or at least as long-lost cousins living in exile – funded schools in a number of towns and villages in Greece and the Balkans. But they imposed upon the villagers the teaching of Romanian, often with the disastrous result of splitting families and severing villages, or prompting an exile to Romania. Many a village viewed the teaching of Romanian as a gesture of arrogance and superiority, as well as intrusion, and as one proud old Vlach bitterly told me in Samarina, a quintessentially Vlach village, “The Romanians came here like our big brothers to teach the Vlachs their native tongue. That’s what they thought. But we are Vlachs, not Romanians. We don’t speak their language and have nothing to do with them. Our histories are different.”

Regarded by some linguists as one of Romanian’s three dialects (Meglen Vlach, spoken in several villages in northern Greece, and Istrian Vlach, are even more endangered), and by others as a separate language, Vlach is at best semi-intelligible with Romanian (arguably less so than Spanish and Portuguese), and most Greek Vlachs deplore any connection between the two. From its inception, the teaching of Romanian in Vlach communities proved nothing short of divisive, in many cases rupturing stability, and appealed only to a small minority in a tiny fraction of their villages. In places where Greek and Romanian schools competed for students, with few exceptions, the Greek schools dominated, resulting in a wrenching, factional divisiveness based on political affiliation. It also swelled the ranks of those who looked longingly to Romania for their forebears.

Despite the topic’s sensitivity, and no matter one’s politics, it is still difficult to discuss Vlach history or language without mention of Romania, though the Greek Vlachs do not look beyond their own borders for their origins. But that has not been the case with all Vlachs. Throughout the last century many families vacillated between a Greek or Romanian ancestry, and those with even a modicum of Romanian sentiments, usually the more financially desperate, left Greece and Albania before and after World War I for the green pastures promised, but not always delivered, by Eastern Europe’s only Latin-speaking country. Though their numbers are dwindling, there are still alive today Vlachs who recall the sentimental pull of these “ethnic” struggles, especially among the Arvanitovlachs who settled in Bridgeport, Connecticut, as well as many of their like-minded brethren in Romania. This politically divisive and incendiary affair still exists within the US Vlach community, though vastly less visible than even a decade ago. But some in that community can still recount the horrors of Romanian schools in Greece burned to ashes, of a famous Albanian Vlach named Papalambru Balamaci, murdered by Greek bands in Koritsa in 1914, and of pro-Greek Vlachs themselves determined to rid villages of any semblance of Romanian education. Anyone growing up in those Farsherot (Arvanitovlach: Albanian Vlach) communities in Albania, or in their sister villages above Edessa in Greece, heard lurid stories of wrenching conflict between the two groups. Consequently, there are today thousands in Romania of many stripes who decades ago left Albania and Greece and later found themselves stranded behind the Iron Curtain, my own family among them, and these are the Vlachs who abandoned their native soil for their “Promised Land” in Romania.

The preservation of language is vital to cultural survival, and in my own travels over the Greek mountains I found it fascinating to examine why some villages preserved it better than others, and why some had lost it completely, as has happened at Namata (formerly Pipilisht), Sisanion (Shishani), and Vlasti (Blatsa) in Macedonia, until Vlachs told me why. It survives best today in villages where the Romanian schools were never established, or were forcibly closed (sometimes by Vlachs themselves), thus lessening the strife inherent in this linguistic and political coflict. In villages where Vlach continued to be spoken as it had for centuries, without Romanian interference, without Romanian schools, the language survived, and in some cases, thrived. Metsovo today is a prime example: in the middle half of the twentieth century it rejected the short-lived Romanian schools, and without a divisive institution within the village the language continued as it had for generations, to this day still heard in its misohori, the village center and gathering place, and even more so in the winding, rustic alleys and homes beyond it. Sadly, this is still an explosive issue in Greece and the topic’s delicate nature traces its origins to the Vlach-Romanian symbiosis, or, as others maintain, the Romanian propaganda thrust upon the Vlachs.

For most Greeks the generic word vlachos (shepherd) holds no uncertain meaning, thus the widespread misconception that the Vlachs (with a capital “V”) are simply seasonal transhumant shepherds pasturing their once huge flocks all over the vertiginous mountains of Greece and Albania (actually, vlachos with a small “v” distorts and demeans the essence of Vlach heritage). The Vlachs are known for their cheese-making, their flokati and spanakopita, and though the Vlahopoula of song may be romanticized, it is fact that they have always been much more than shepherds. Truth be told, this far-flung community has sent forth many leading figures in the Greek world of politics, professions, and the arts (the first prime minister of Greece Kolettis, the poets Krystallis and Zalacostas, the revolutionary Rigas Feraios, as well as names like Averoff, Tossitsa, Sturnaras, Farmakis, Zappas, Mitropanos, Kaldaras), while during the Greek War of Independence many klephts and armatoles (bandits and mercenaries) emerged from Vlach communities. The late Archbishop Athenagoras was himself a fluent Vlach speaker from Epirus. Less known, however, is the enormous business success of immensely rich Vlach merchants throughout The Balkans. The renowned Moscopolis, in Albania, once a predominantly, or perhaps entirely, Vlach town (with a Greek exterior) – the Vlach Jerusalem, as one Greek writer recently stated – resonates in Balkan history with its vibrant education and commerce, but with its final sacking in 1788, the Moscopolis Vlachs dispersed in many directions, only to enterprisingly set up shop in other towns and cities all over the Balkans. Much can be said as well of Siatista, in Greek Macedonia, where octogenarians once told me (in Greek) they “used to be Vlachs from Samarina,” while praising their town for the many achievements of its native sons scattered across Europe. Where diaspora Greek communities flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries, whether in Serbia or Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Egypt, Russia, or in Vienna itself, these urbanized Vlachs, with connections all over the Balkans, contributed vigorously. But most never returned to their homeland, and with the riches accumulated in exile, assimilation took its toll. From this perspective one gathers just how far this community stretches beyond the pastoral, transhumant life with which it is so often associated. As one friend sharply reminded me, “We live in Greece, make our living in Greece, and we don’t progress in society by waving Vlach banners.”

A four-part work published in Greece entitled “Studies on the Vlachs” by Asterios Koukoudis, a grade school teacher in Thessaloniki, is a richly informative study. Its author, a Vlach on his father’s side, engages the reader with abundant and remarkable documentation of the Vlachs’ many achievements in Greece and the Balkans. Koukoudis, who grew up curious about the language he could not understand from his father’s family, and belatedly tried to learn, examines with acute insight their various communities in Greece and the Balkans, among them the Arvanitovlachs. His numerous maps document mountain villages in Roumeli, long Hellenized, that last knew they were Vlach sometime back in the 1800’s, and today of course it would be indiscreet to remind the villagers of their possible origins, which I unwisely did on one visit. Prudently, and perhaps admirably, Koukoudis skirts around the ethnic issue by asking not “what” but “who” are the Vlachs, choosing instead to touch upon the many venues in Greek history where they’ve stamped their imprint. He alludes as well to the “Romanian propaganda,” historically a fairly new phenomenon, and while emphasizing the Vlachs’ Greek patriotism, he manages remarkably well, perhaps inadvertently, to hint that they are a community unto themselves, assimilating and adapting, when necessary, but clinging to their own ethos in private. “Studies on the Vlachs” is a scholarly work, packed with information never before so copiously recorded, and Mr. Koukoudis, with his insider’s view, has emerged as a vital spokesman in this improbable and blossoming field of study.

But the work which first cast a spotlight on the Vlachs in the English-speaking world arrived almost a century before Koukoudis. Published in 1914,The Nomads of the Balkans by Wace and Thompson remains the unofficial bible of Vlach studies. The book resurfaced in the early 1970s and, as it turned out, energized the Vlach community in the US. This classic offers a workable vocabulary of the language and its various dialects, details journeys to dozens of Vlach villages throughout the Balkans, covers what was known of Vlach history, and depicts Vlach life in the years leading up to World War I. Largely outdated today, it holds a timeless appeal as a window into a vanished way of life.

In 1909 near Almyros in Thessaly, the Vlachs became a serendipitous discovery for the two British archaeologists: through a hired muleteer, they learned of a Latin-speaking, bilingual population inhabiting entire villages in Greece and the Balkans. Seized with curiosity, Wace and Thompson, whose names are still known in Samarina, abandoned their digging for five years to travel with the semi-nomadic Vlachs to their many villages scattered all over modern Greece, Albania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria. It is interesting today to pore over The Nomads of the Balkans and read about Vlach villages in the Pindus mountains in 1910, places where school children were ordered to speak only Greek while the suspicious British strangers were present, and in another, where they were assured only Greek was known, only Vlach was spoken. Eagerly tracing the steps of Wace and Thompson, I walked into several villages that were thoroughly Vlach-speaking back in 1910, only to find no vestiges left of the language, not even among the old. That is because some were being Hellenized even in Wace and Thompson’s day, and in one, I was led to its lone speaker, a sprightly 90 year old who delighted in using his native language for the first time in decades. The old man, imbued with a sense of history, sharply reminded the young, incredulous, and irreverent crowd that had gathered that we were speaking what once was, long before their time, the only spoken language in their village.

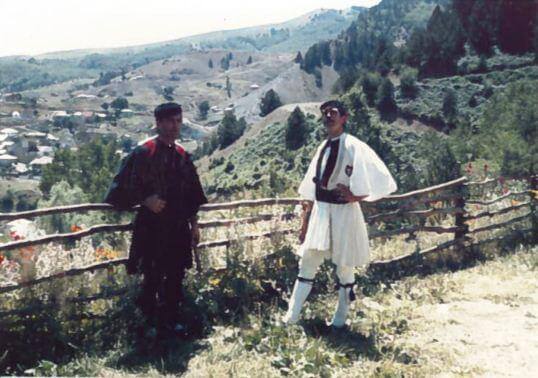

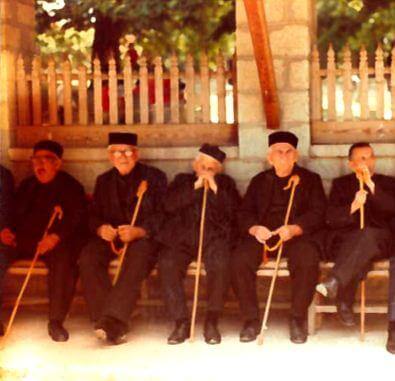

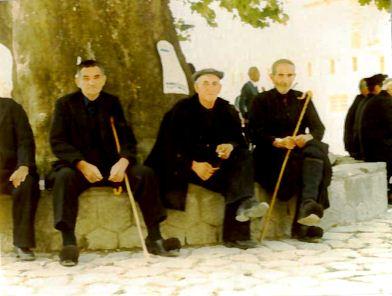

Many Greek tourists to Metsovo are often startled to hear this unintelligible language spoken in their own country. What, some wonder, are they hearing in the heart of a Greek village? Sitting one evening with some retired shepherds in a noisy Metsovo cafenion (café), resplendent in their black cloaks and delicately carved shepherds’ crooks, a Cretan family at the next table listened intently, curious about the strange language that surrounded them at every table in the village of Mr. Averoff-Tossitsa. They had no idea, they told the Metsovites, that Vlachs speak their own language, and not a rural northern Greek dialect, and that a visitor from Romania will make out some details of conversation. Drawn to the rustic charms of Metsovo, they walked away with a bit of its culture and language, and the venerable, kilted old men who gather in the misohori, each year dwindling in number, have always delighted in reminding tourists of their bilingualism.

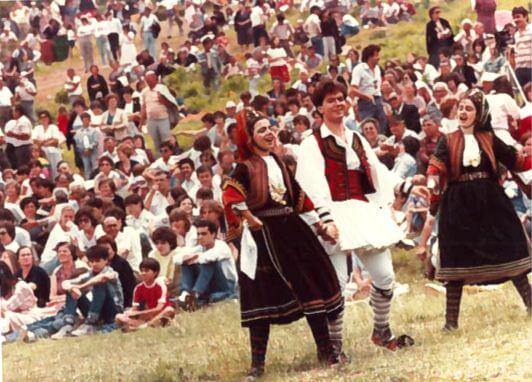

But every now and then there is agitation, fired by the notion of “minorities” existing in Greece. Sotiris Bletsas, an architect from Naoussa, repeated his first year in school because he “couldn’t express himself in Greek,” by no means unprecedented for a Greek Vlach. At the annual Pan-Hellenic Vlach festival in 1995, Mr. Bletsas innocuously handed to an official a pamphlet (in English) from the European Bureau of Lesser Used Languages (EBLUL), listing some of Europe’s and Greece’s lesser-used or minority languages, his own among them. The gesture brought trouble for Bletsas and an unexpected day in court. Charged with “dissemination of false information” on minority languages in Greece, the Greek patriot was sentenced in 2001 to 15 months in prison and a 500,000 drachma fine, topped off with a lecture clarifying that his mother tongue was nothing more than an idiom! Ultimately acquitted, in large part due to international attention that included the Greek Helsinki Watch, the case demonstrated without question that other language groups exist in northern Greece. The reality of “lesser used” languages, like the Slavic language still spoken in towns and villages like Florina and Aetos in Macedonia is not lost on many Greeks, and disclaimers to the contrary more often than not represent the “unofficial” government stance. The Bletsas case shocked many people, but was not without its humorous side. Parodoxically, two witnesses for the prosecution were overheard just outside the courtroom speaking to each other in Vlach, one being the mayor of a small town in northern Greece! But this comes as no surprise, since many, like Mr. Averoff-Tossitsa, are often the most vocal opponents of their own language. Bletsas is now free and by all accounts determined to work for the preservation of his native tongue. “It would be a real shame if I wouldn’t. I owe it to my language and community,” he remarked after his acquittal. And in that light, there is hope that Greece’s representation in EBLUL, with the maverick architect a ranking member, along with others marching for their “lesser used” languages, will look with insight into the frequently denied linguistic diversity of the country.

Nymphaion (Neveska) in Macedonia, ancestral home of the Boutaris wine family, is a charming village, one of the most striking in northern Greece, and a bit haunting as well. The Neveskiotes’ business acumen speaks of a long history of emigration and commercial success in Greece and beyond, echoing distant recollections of long abandoned Moscopolis. But on one visit my enquiry into the village’s retention of its ancestral language rattled nerves. At a small café gathering, a well-traveled summer resident of the village informed me of the benefits of bilingualism. With a scholar’s curiosity, he eagerly enquired into the preservation of Native American languages, of the position of Spanish in the United States, and above all was most concerned that Greek-Americans preserve their language in the diaspora. But the preservation of his first language was another matter, and with it his mood shifted from scholarly to provincial, and I had to tactfully fight off a small army of temperamental Vlachs indifferent to the language they spoke so well. He preferred instead to toe the “politically correct” line and let it die of attrition, and, as a polyglot, was not in the least mindful of the impending demise of his mother tongue.

What is certain is that Greece will continue to lure visitors worldwide to its enchanting shores, but I have crossed paths with travelers disillusioned by overcrowded and overpriced tourist destinations, finding them instead in the most unlikely places, curious souls searching for the experience of some genuine Greek culture and folklore. Over dinner one evening with a former mayor of Thessaloniki at the city’s famous Olympus Naoussa restaurant, our discussion of the Anastenarides firewalkers at nearby Langhadas nostalgically evoked cultural recollections for the mayor, as if transported back in time. Aware of Greece’s various “societies,” he knew the Vlachs and their business influence in his own city; in fact, he feared their culture might end up in a folklore museum’s period room, a silken cord symbolically drawn across it as a reminder of a vanished time. Similarly, flourishing museums now house the history and cultural artifacts of the once nomadic Sarakatsans, a fascinating group of Greek origin that is sometimes confused with the Vlachs (read John Campbell’s Honour, Family, and Patronage), as well as the mysterious Karagounides of Thessaly, themselves so often thought of as Albanian Vlachs. The mayor questioned how much longer people would feverishly walk on burning coal at Langhadas every May 21, knowing that these communities, however long they survive, serve as a link to the past.

And in the brilliant and varied tapestry that is Greece, what will become of even the best Vlach-speaking villages as they confront a high-tech world indifferent to obscure, unwritten languages? Today the Albanian Vlach villages of Argiropoulion (Karajol) and Sesklo, in Thessaly, proudly retain Vlach, and in Fourka and Distrato (Briaza), Milia (Ameru) and Palioseli, in Gardiki and Kastania, one can still hear their weathered Latin language in the high passes of the Pindus range. But can and will they pass it on to future generations? Will the young embrace their ancestral tongue simply for the sake of nostalgia, though otherwise impractical? And can the enterprising Vlach Association of Veria step up and preserve, if nothing else, their linguistic legacy? (In fact, fledgling language courses have recently begun there.)

Without question, the Vlach-Aromanian community has always stood at the vanguard of Greek patriotism, and one can neither negate nor fault this loyalty. Above all, patriotism is a personal matter, and a distinct home language, culture or religion need not interfere with a larger national patriotism. But some Vlachs, against difficult odds, have asked for the preservation of their endangered language, not to be used as a political tool, as some have done, but simply to preserve it as a reminder of a history that has not always been accurately portrayed.

Photos by George Moran

Responses