Nationalism vs. the Vlachs

I celebrated my sixty-fifth birthday in Sarandë, South West Albania. This is easily reached by boat from Corfu, and is a safe and pleasant place to take a holiday. There are Vlachs in the area and all over Southern Albania. I have recently written about these Vlachs in a book entitled Badlands, Borderlands. Rather disappointingly many of these Vlachs do not seem to have a particularly long history. On the contrary some of them claim to have been perpetual wanderers, only give houses after the war by the now discredited regime of Enver Hoxha.

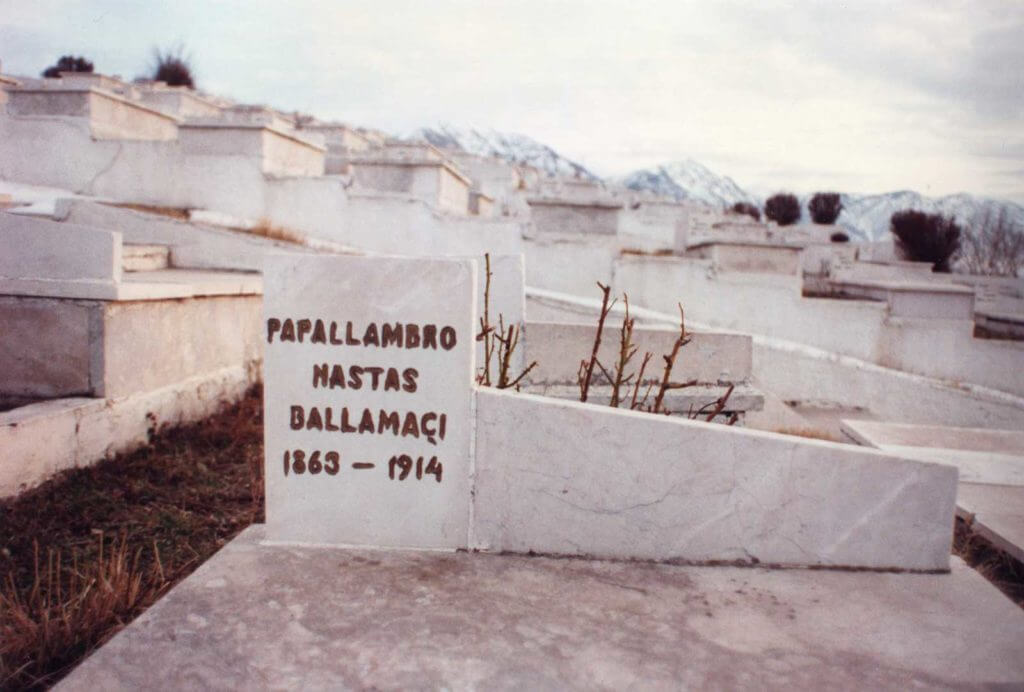

This is not the case in the South East of Albania where there are several Vlach villages with a comparatively long history. Pleasa famous in the annals of the Society Farsarotul is one of these villages, although again rather sadly the young people of Pleasa are now working and living in Greece. The same absence of all but the very young and the very old can be found in Voskopojë, the most famous Vlach village which in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a town of considerable wealth.

There is still a long gap between Voskopojë in the seventeenth century and the ancient Romans. In my latest book I tried to fill this gap with speculations about the Byzantine city of Diabolis which I think is to be found near Pleasa and Voskopojë. Archaeology is difficult in this area where Greece, Albania and the former Yugoslavia meet, and out literary sources, Byzantine or Italian, are vague on geography and ethnicity. But this is the area where Vlachs are first mentioned in history, killing the brother of a Bulgarian tsar in 976 between Prespa and Kastoria.

There is still a gap of about four hundred years between 976 and the last known appearance of Latin speakers in the Balkans, when they would seem to have occupied the North Western section of the peninsular with the South and East speaking Greek. Some Roman citizens continued to speak but not to write native languages, and it is to this fact that we owe the survival of Albanian, but Greek and Latin had a superior status and had it not been for the Slav invasions would probably have divided the Balkans between them today into Latin and Greek speaking areas.

As it is Slav languages predominate in most Balkan countries with modern Greece, Albania and Romania the only states to have a non-Slav language. The Vlachs in their scattered pockets are a rather embarrassing reminder of the times before the Slavs when the great Byzantine emperor Justinian, himself a Latin speaker, ruled over a population of mixed race, but rather a different mixture than at present.

It is here that we have to face the difficulty that history in the Balkans tends to take a nationalist tone. For the Albanians it is important to establish that they are the descendants of the ancient Illyrians and have always occupied their ancestral lands. It is therefore difficult for them that there are still Vlach and Greek speakers in the south of the country, and there would appear to have been more in the Middle Ages. For the Greeks the Vlachs are the descendants of Roman legionaries and Greek mothers, set to guard mountain passes, although it is odd that these descendants should learn languages at their fathers’ knees. For the Romanians he Vlachs are the country cousins who mysteriously and motivelessly detached themselves in the Middle Ages from the main group of Latin speakers north of the Danube, this group having equally mysteriously adopted Latin as its language in spite of being occupied by Rome for less than two hundred years.

It is possible that the answer to the problem of the Vlachs lies in the area I intend to make the object of my next book, namely Northern Albania. This is difficult and dangerous country. The Roman conquest which took place at the beginning of our era did not as in France or even in Britain produce many tangible marks of civilization such as towns or roads. On many classical atlases apart from a few sites on the coast there is almost nothing to show in the interior. The occupation of the Romans like that of other invaders cannot, given the physical conditions of the country, have been very intensive. Albanians, fiercely proud of their independence, insist on this point. They point to the survival of Albanian to prove it, and maintain that material remains found at various sites in Northern Albania, notably at Komani near Skodra and Kruja, later Scanderbeg’s capital, dated from the seventh to ninth centuries AD, are proof that there was a continuity between the ancient Illyrians and the modern Albanians.

Others think differently. The Serbs, anxious to prove their claim to Kosovo, point out that there is no proof that the Komani-Kruja culture is necessarily Albanian or Illyrian. The English archaeologist Wilkes thinks that the sites may well have been the work of the Latinized inhabitants of Northern Albania perhaps a little more civilized than some of their neighbours who continued to speak their native tongue. With the collapse of the Roman empire and the Slav invasions both Latin and Illyrian speakers would have retreated to the hills and obscurity, although there is a mysterious mention of Romanoi in this area by Constantine Porphyrygenitus in the tenth century. With the reassertion of Byzantine authority at this time both groups enter history again;and chroniclers now talk of Vlachs and Albanians. With the collapse of Byzantine power in the thirteenth century both Vlachs and Albanians moved towards more prosperous pastures in the South. The Ottoman conquest in the fifteenth century and the subsequent conversions to Islam finally put paid to the survival of Vlach in Northern Albania, although there were many Vlach speakers in Kosovo within living memory,just as there are surprising mentions of Vlachs in Serbian chronicles of the fourteenth century.

Most of this is hypothetical and will be open to objections for lack of evidence. I hope to find this evidence in visits to Albania. Such visits will not be easy. I am open to offers of help from younger, fitter, braver and better qualified workers in the field. At the age of sixty five some say that I should be cultivating my garden. I am however drawn on by a wish to prove the folly of nationalism in history. Nation states are rightly keen to draw the attention of their citizens to their national heritage. In Albania where first communism, then shallow materialism were forces that acted against, culture, it is only proper that the history of Albanian should be properly appreciated. But this does not mean that we should ignore the fact that in the middle ages parts of Albania were inhabited by people who spoke Greek, Slav or Vlach, or perhaps all of these as well as Albanian. We are all member s of the human race. Albanian nationalists like Greek, Romanian and Slav historians, appear to ignore this.

Responses