The Unwritten Places

Editor’s note: We are delighted to offer these excerpts from Tim Salmon’s extraordinary new book, The Unwritten Places, a sensitive account of his travels with Greek and Vlach shepherds. We thank Tim Salmon and his publisher John Chapple for their kind permission to reprint these sections. The book is now available through the Society’s bookstore; see order form on the last inside page of this issue.

The shepherds who traditionally have pastured their flocks in the Agrafa are Sarakatsáni. I shall describe daily life in the sheepfold later in this book, for I have experienced it much more immediately with the Vlachs, the great rivals of the Sarakatsáni, who live further north in the Pindos. Both peoples are nomads or semi-nomads — or were, at least. But, unlike the Vlachs, who have villages close to their summer pastures in the mountains, the Sarakatsáni have no settled homes. They live in huts of stone, brash or reeds in both mountains and lowlands. The Vlachs call them contemptuously skinítes or tent-dwellers, while they just as cordially despise the Vlachs for living in houses and being “foreigners.” And therein lies the second major difference between them: the Vlachs’ mother tongue is a Latin-based language akin to Roumanian, while the Sarakatsáni speak Greek. In fact, on the evidence of their dialect, customs and art — in particular, the characteristic geometric designs on their dress — scholars believe that they are among the most ancient and perhaps “purest” Greeks, maybe even directly descended from the Dorian invaders. For by their practice of endogamous marriage — oúte dhíname, oúte pérname, they say, like the Vlachs: “We neither gave brides nor took them” — and their nomadic way of life, they escaped outside influence right up until the Second World War.

Like the rest of Greece’s rural population, however, they have not escaped the changes of the last thirty years: urbanization, modernization, changing values and the general rejection of the old ways. Ironically, and probably because of their “Greek-ness” and “homelessness,” they have been more susceptible to these changes than their rivals, the Vlachs, whose possession of villages has given them a slightly stronger economic base and whose different speech makes for a stronger sense of ethnic identity.

Few Sarakatsáni today seem willing even to acknowledge their “tribal” identity. Most, even among those still engaged in the pastoral life, have acquired houses. And I have never seen anyone wearing a single item of the traditional dress. There is in fact little left to distinguish them from any other livestock farmer forced by climate to spend part of the year in the mountains.

A few famous names from the days of the great tselingáta, albeit much reduced in circumstances, can still be found in the sheepfolds around Vrangianá. There is still a Malamoúlis at Megála Krithária. The huts at Kamária are still peopled by Tsingarídhases, where I noticed the date 1872 inscribed on one of the hearth stones. The family has probably been grazing those pastures for many more generations than that, but it is rare to find such concrete evidence in such impermanent dwellings.

The young wives were at pains to point out to me that they had real houses now, near Livadhiá on the Athens-Delphi road. Dressed in city skirts and blouses, their hair more or less recently “done,” they apologized continually for not serving me with proper cutlery and crockery. “You must come and see us at home. It’s not like this there. Television, furniture. . . nice, modern. We’re going to go down there soon, when the sheep have stopped milking. We’ll leave a hired shepherd and just come up once a week to bring supplies and keep an eye on things.”

They had just had a track bulldozed up the mountain from the village at its foot, passable for their pick-up in dry weather. Only their mother-in-law, who was sewing a lace tablecloth by the light of a triple likhnári — a little clay lamp with a wick burning in olive oil — said to me when we were alone that she hated the lowlands, hated living in a house. She was seventy. “You can’t breathe down there in the kámbos,” she said. “The heat. I long all winter for the spring to come to return to the mountains. In the old days we came up on foot. It took three weeks with the sheep, mules, dogs, chickens and families. We tied the hens on the saddles and carried the babies. It was hard but it was beautiful. The young don’t know anything about that.”

* * *

…In the city, familiar landmarks are bulldozed every time you turn your back. In the mountains, rubble from a new road is casually pushed into somebody’s field — and, God knows, there is little enough arable ground anyway — or tipped down the mountainside destroying trees and filling rivers. Why should these men’s path, their trade route, their life-line, their road to work, that has lain upon these slopes as lightly as the leaves for generations and generations, from boy to man to grandfather, as witness their autographs bulging now and distorted by the still growing bark of the trees they carved them in, why should this path be obliterated as of no account on the say-so of a man behind a distant desk?

It was dusk when we came to Ghióni, a beautiful clearing among beech trees, where a slow, clear spring just perceptibly dimples the surface of the water held in a hollowed lip of log for the convenience of the drinker. The ground round about had been rooted over, as if by pigs.

“Boar,” said Karayiánnis.

We stopped to drink and smoke.

“Yerásame, Thémi. We’ve grown old,” said Karayiánnis, unslinging his blue wool jacket from his shoulder and lowering himself to the ground.

His white hair stuck in sparse spikes from his brown scalp. His face was creased and his shoulders were a little bent, but still, at sixty-two, his legs devoured that slope with the steady regularity of pistons. His was a very Vlach build, short and square-shouldered, strong without being heavy, with a broad brow and fine bony nose set very square to the eyes. Hard to describe exactly, but there is very definitely a Vlach physique, and character too, in a general sense, whose most marked feature by contrast with the Greeks is a certain reserve.

* * *

At last, with another satisfied “Pollá ípame — we have said many things,” Tsiógas brought the conversation to an end.

“We’ll make our water and I’ll walk you to the tent, so the dogs don’t eat you.”

“You’ll be cold,” said Stéryios.

“No, I won’t. Truly. I’ve got everything I need.”

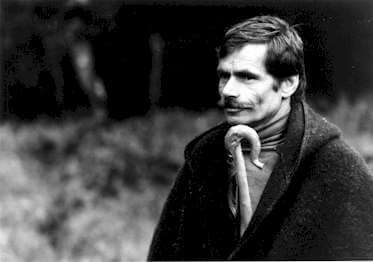

“Take the malyótu to put underneath you.” [Malyótu is the Vlach word for the heavy black goat’s hair cape all shepherds carry for protection from the weather. It is also known as a tambari.]

Though they think nothing of roughing it themselves, they are appalled at the idea of somebody else doing so, especially an educated person from the city. “We are hardened to it — skliragoyiméni,” they say. It is part of a shepherd’s life, but the idea of choosing hardship, and even more the idea that enduring hardship could actually be a form of pleasure, is quite inconceivable to the Greek mind.

For most Greeks the good life consists in the avoidance of effort, of all exertion, whether physical or intellectual. “Why do you run about hither and thither? Why do you give yourself a hard time and go climbing up mountains?” says a friend. “Me, all I want,” he says, “is to sit here in the shade, do nothing, drink a cold beer. That’s what life is about.”

Vlach shepherd with crook (carligu) and cape (malyotu or tambari)

Although it seems to confirm Western prejudice about Levantine far niente, I think this attitude is relatively new, or at least the wide extent to which it afflicts contemporary Greeks. It is a lowland phenomenon, which means essentially urban, newly rich, newly emancipated from the bonds of traditional peasant life: that growing constituency of Greeks for whom the possession of to vídeo is the acme of terrestrial bliss. It is a product of alienation. It is an attitude that a Vlach who still lives as a Vlach is not capable of formulating.

Lying on the ground in my tent I was thinking how you never hear shepherds say they are tired. They do not, as it were, come home from work full of moans and groans, wanting to do nothing but cease work and put their feet up. Look at Tsiógas and Stéryios. They were ready to go to sleep, as who wouldn’t be after running up and down a mountain all day? But I have never heard them speak of the tiredness the Horlicks advertisement tells of, the weariness that is compounded of tedium, reluctance, the sense, at least to some extent, of being used and exploited, of not really doing what one would like to be doing. A Vlach is a Vlach is a Vlach! In being shepherds, they are being Vlachs and in being Vlachs they are being themselves. Their lives are integrated. They are whole and that is a real blessing.

* * *

At about two o’clock there was a break for lunch. Everyone, children included, stretched out on the grass in the shade round a rug spread with a feast of cheese and olives, spinach pies, potatoes, salads, spam, bottles of wine and beer and the crisp and succulent flesh of the roasted lamb: a real fęte champętre. I was plied with food, the choicest morsels proffered on a fork, while everyone else ate with their fingers — with the usual injunction to “Eat, eat.”

“It tastes better in the open air,” they said, “and ksápla — lying on the ground.”

Blind Bárba Yiánnis epitomized this attitude. He is the quintessential Vlach. Short and stocky, he lay stretched on one side, ankles crossed, one knee slightly raised, head propped on bent arm, cornel-wood crook tucked in beside him. He looked completely comfortable: the practice of a lifetime spent sleeping, eating, waking on the open mountainside. Like many of his generation, he still dressed the part, in his homespun suit of Vlach blue, spun and woven by his wife from the wool of their own flocks, and on his feet the hobnailed leather clogs with a black pompom on the toe called tsaroúkhia.

“Do you know vlákhika [the Vlach language]? he asked me. For although they use Greek when speaking to me, together they rattle away in their mother tongue, full to the uninitiated ear of uare, nare, ts, ts, ch and esku.

“Tim knows it all,” answered the others.

“Not true,” I said. “I pick up certain words like pene, apa, multu, lupu, buona tzour. . . from Italian and Latin, but I can’t say a sentence.”

“In the war, when the Italians came, we could understand something, talk to each other roughly,” said Bárba Yiánnis.

“It’s like Roumanian,” said another.

“We can’t make ourselves understood with them. It’s another dialect.”

“We are Romans,” said Bárba Yiánnis, his blind eyes lifted towards me. “Arumani. History does not write it, because vlákhika cannot be written. But we know everything from our fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers.”

“What do they call that man, moré, who wrote a book?” Vassílis asked. “What is his name?”

“A. J. Wace,” I said, “an English archaeologist who did the digging at Mycenae. They had a muleteer from Vlakhoyiánni one summer and they did the dhiáva with him in 1910. They went up to Samarína together.”

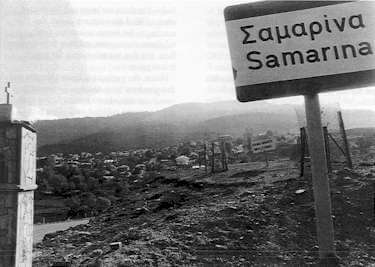

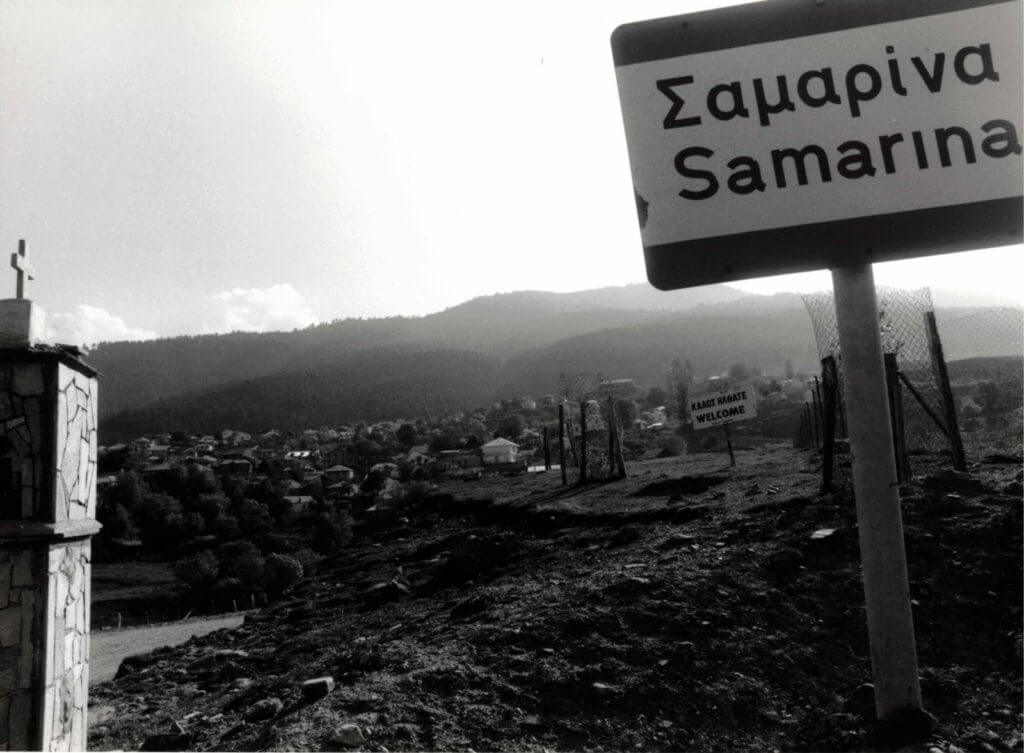

Samarina

“And now you’re doing it! We have close relations between Samarína and England,” they said.

After lunch Vassílis drew me aside. He is the youngest of the brothers, the one with the most obvious worldly charm and the public relations skills, the one who liaises between the enclosed world of the shepherds and the world of commerce and the towns.

“You go with Matoússos,” he said, “to Ambelóna.”

Then he gave Matoússos his instructions. Matoússos, who is Tsiógas’s father-in-law, did not seem too committed to the idea of finding a flock of sheep for this peculiar foreigner. “Who does the dhiáva now? They’ll all be loading on trucks.”

Names were mentioned. “Kótsu, who married the daughter of Ligoúras.”

“Tut,” said Matoússos, jerking his head in an emphatic no. “They’re loading.”

“Mikhális, the son-in-law of the Liupéi.”

“Tut. They’ve got a wedding.”

“No, no, you’ll find someone,” Vassílis insisted. “And afterwards you’ll go to Makrikhóri. Karatássis for sure will be going. He goes every year.”

I was still infected with Vassílis’s optimism, but one thing troubled me and I waited for an opportunity to speak to him privately.

“I don’t want to be a burden,” I said. “Eating all their food and so on. I’d like to pay something, contribute something.”

He would not hear of it. “You go sistímenos, recommended by us. They are our people. Payment would be an insult.”

I was despatched home with the women and children, the fleeces and the old folk. We got the old granny into my car without difficulty, but Bárba Yiánnis, quite unused to cars as well as being blind, had literally to be fitted in. We had to bend his head, lift his legs and slide his bottom on to the seat.

The family home is on the edge of the village, apart from the main huddle of houses. I wondered if that was in itself an expression of Vlach separateness.

There are many things I don’t know. I ask a lot of questions — too many I sometimes

feel — but there are large and fascinating areas of life I dare not ask about: the marriages, for instance; internal family relations; the women and how they see their lives, but that is a taboo area for a male investigator.

Home, the patriarchal home (Vassílis and Stéryios now have separate houses of their own), consists of two houses facing each other across a cobbled yard. One is the original stone cottage where Bárba Yiánnis was born, now used as a store for loom, wool, rugs, the old woollen tents and so forth. The other is a modern two-storey cement structure, whose low beamed downstairs belies an older past. At the back is a half-covered yard for lighting fires, heating water and washing. There is a primitive, unflushable WC — pedestal only. As in any farmhouse, life revolves around the kitchen. Apart from the seldom-used parlor upstairs, furniture is limited to the essentials: table, chairs, beds. Decoration is chiefly the beautiful hand-woven rugs (veléntzes) and runners on the beds and walls.

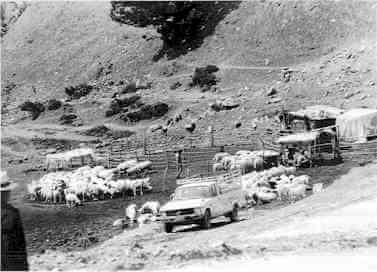

Motorized migration (dhiáva)

In summer the yard becomes the living-room and that is where I sat with Bárba Yiánnis, waiting for Matoússos to come and take me to Ambelóna. He said he had done the dhiáva on foot every year of his life except 1948 and 1949, right up until he lost his sight in 1982. No one had gone up to Samarína in ’48 and ’49 because the Civil War was raging up there. His own brother had died at the hands of a last lingering group of Communist guerrillas in 1950, a year after the official end of the war. They had taken thirty sheep, then killed the brother and a hired shepherd to prevent them betraying their whereabouts to the government army.

“Before the war,” Bárba Yiánnis said, “before they closed the frontier, there were Samariniotes who used to take their flocks down into Albania for the winter.”

Granny, in her old-fashioned black floral print dress and thick wool socks, was spinning as we chatted, with a distaff shaped like a wide-pronged Greek psi shoved inside her bodice and wedged under her armpit…

“We used to make everything out of wool,” she went on, “like what Grandad is wearing. That is all he will wear, but the young want those,” she said, pointing to my jeans.

* * *

…They were a dignified couple, the old ones, with a serenity that the younger generation does not share at all. For them the worm has entered the rose.

Vassílis had appeared with a shepherd named Kóstas from the neighboring village of Verdhikoússa on the beech-covered slopes of Mt. Oxiá above Vlakhoyiánni, whose services he had just engaged as an extra hired hand for the summer season. Chipping into the conversation, he said, “For the old ones, it was a good life and they knew no other. The whole family was involved, labour was cheap and plentiful.”

Now tradition has lost its sanctifying power and the ways it sanctified have been made to seem old-fashioned and backward. Only the hardship is remembered, being out in the cold and the rain, doing everything by hand. “Vlach” or vlákhos in the mouths of Athenians has come to mean an uneducated, moronic yokel. Many Vlachs no longer teach the language to their children “because it is demeaning.”

Doubt creeps in. Self-esteem is damaged, and it is harder to make ends meet in the new economic conditions. “A hired shepherd costs half a million drachmas for six months, and no one wants to do the work any more,” Vassílis said. “During the spring dhiáva you have to milk twice a day, make the cheese and dispose of it to villages along the way. . . . If you go by truck, the state pays half the cost and you’re in Samarína in four or five hours instead of three weeks. There . . . choose!”

And yet. . . . when Granny mentioned the konákia (the places where they camped at night) and the woven tents and Vassílis riding off with the mules every morning to sell the cheese in the villages round about, for there were no cars or roads twenty years ago, she struck a deep vein of nostalgia.

“It’s marvelous,” Vassílis said, “when the weather is good.” And Kóstas, the newly hired shepherd, although not a Vlach himself, agreed. And they waxed unexpectedly lyrical recalling the last time they had done the spring dhiáva on foot.

“Besides, it’s better for the sheep,” Vassílis said. “They don’t get shaken around in the lorry. They have time to acclimatize to the difference in altitude. . . and it’s free grazing on the way!”

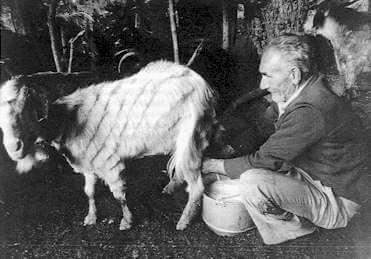

Beasts’ burdens: first shearing, then milking

* * *

Within three days I was on the road again. Vassílis had phoned to say he had found a man with a herd of nine hundred goats.

“Goats?” I repeated.

“Never mind. It’s the same thing,” Vassílis said, sensing my disappointment, for goats are less aristocratic than sheep. “They are going to Dhotsikó near Samarína. I don’t know the man personally. His name is Kómbos, but we’ve got a relative who’s working for him. They’ve started already, so come at once. You can catch them up at Elassóna.”

I caught the bus this time. I had to change in Lárissa. The waiting-room for local buses was different from the inter-city one, much more rustic and old-fashioned. Among the dozen or so villagers sitting around were two elderly Vlach shepherds playing the aristocrats of the mountains. One was a handsome old chap dressed all in black, with a dashing white forelock falling across his forehead and spreading white moustaches in startling contrast to his tanned, deeply lined skin. He ambled slowly up and down the room, trouvás and jacket slung nonchalantly over one shoulder, one arm on his friend’s shoulder. And as he went he rolled his crook across his body with the majestic swagger of a drum major, placing the tip with pinprick precision, then sweeping the top away from him in a broad languorous gesture terminated by a little flick of the wrist. All his gestures bespoke a lordly contempt for the plainsman and the things of here below.

* * *

In the exchange of populations with Turkey in the aftermath of the Smyrna disaster in 1922, thousands of Greeks from the Black Sea provinces were settled in the area and given land, causing tension with the locals who were also eager to lay hands on former Turkish property. As we talked, an old lady came in who had narrowly missed being born in Trebizond. Her four sons, she said, had emigrated to Germany in the 1960s. Would they come back? I asked. She said they would stay to get their pensions first and then return, for, like the emigres to the US with their $500 a month, the money went so much further in Greece.

In spite of his avowed friendship with Mikhális, the shopkeeper trotted out all the usual prejudices against the Vlachs: how they were Jews, the sixth tribe of Israel, and collaborated with the Italians when they invaded Greece in 1940. He also produced the story, which is true, about a pro-Mussolini teacher called Dhiamantís who returned to Samarína during the Occupation and tried to set up a fascist Vlach state, the Principality of the Pindos. It is possible that the idea of autonomy struck a chord in some nationalistic Vlach breasts, but they certainly were not the collaborators he accused them of being.

* * *

Time passed. I got up to wander back to the center of town and a man from the café opposite crossed the square towards me staring hard. His face seemed familiar.

“Don’t I know you from somewhere?” he said. It was Lákis, son of the tavern-keeper in Samarína. They were going up in a few days, he said; there was a lot of snow still. We had a drink and he directed me to a cheap hotel, run by an acquaintance. We arranged to meet for a meal.

He came and fetched me from the hotel, anxious to know if I had been properly looked after. I hardly knew him, but we ate and drank and talked with a warmth and openness that I have never encountered anywhere except in the Greek countryside.

Unlike many of his generation — he was about thirty — Lákis was proud of Samarína and his Vlach origins. He would certainly teach any of his children Vlach, he said. Perhaps he had had more education than most, though I doubt it, but he was certainly more thoughtful and aware. Perhaps it was due to the tradition of left-wing activism in his family, the Communist Party encouraging its own to improve themselves. Two of his uncles had fought in the Civil War on the Communist side. One had been betrayed by a teacher and shot after conducting a captured regular army officer back to safety. Another had spent thirty years in exile in Tashkent, where, in the early ’50s, Russian troops had had to intervene to quell violent internecine strife among the Greek Party exiles. Disillusioned with socialism in the east and with left-wing politics in Greece, this uncle attributed these failures to the fact that in eastern Europe Communism had been imposed by a conqueror on peoples who had contributed nothing to the struggle against the Axis powers, whereas in Greece, where the people had fought for change, the Great Powers had intervened to smother those hopes.

Even after the so-called restoration of democracy in Greece in 1974, Lákis said, the old Civil War mentality, the anti- Communist hysteria inspired by the Americans, had persisted in many branches of the state. When he was doing his military service in 1978, he was summoned by the military police shortly after reporting to his unit and asked why he used to sell the Communist Youth newspaper, Kathodhigitís. “They still had files on everyone,” he said. “And what a waste of talent. Anyone with any intelligence and education who thought for themselves was suspected of being left-wing and put to doing futile, menial tasks like digging holes.” The authorities had told him, “If you sign this paper renouncing your ideas, you’ll be okay. Otherwise, if you ever want a job as a public employee, forget it.” Their retaliation for his refusal was to extend his service by six weeks “for plotting.”

Again unusually for someone of his background, he had had the enterprise to travel with a cousin to Paris, where a friend was studying, and on to London, watching their pennies carefully all the way. Their

greatest surprise, he said, had been to hear Vlach spoken in Switzerland! It was Romansch — a similarly derived Latin dialect.

In the morning I decided to play my last card and take the bus to the konáki at Mustafá. Today it lies in a loop of the Kalambáka-Grevená road at the foot of the long climb on to the ridge above the Venétikos river that marks the start of the ascent into the foothills of the Pindos, whose main peaks smudge the western horizon, featureless with distance beyond the unravelable relief of the intervening woods. There is nothing there but a walled spring and behind it a stretch of marshy grass shaded by scattered oaks: one of those mysterious, unmapped places where Vlachs have halted on their transhumant journeys for centuries and where, even today, the right to camp, graze and cut firewood is still protected by law.

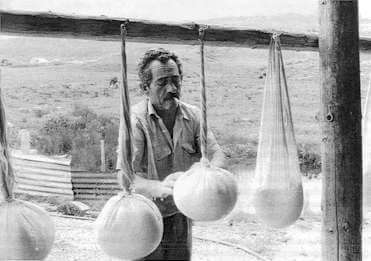

The cheesemaking place (casharu)

Mustafá seems to be a particularly evocative name in the folk-memory of Vlachs heading for the pastures of the northern Pindos. Several dhiáva routes came together here, where friends and relatives from different winter quarters in the lowlands, who had not seen each other since the previous autumn, would meet and exchange the news and travel a few days together before parting, some to turn southwards to Perivóli and Avdhélla, others continuing on to Samarína. And what a sight it must have been, as those who experienced it recall with nostalgia: the camp fires burning by the striped wool tents, the children playing, wives and grandmothers cooking, the cheese being made, the squabbling of dogs, the patient pack animals, the restless chiming of the bells on the sheep and goats.

But for me Mustafá remained stubbornly empty. I had to see all that in imagination. I lay on the grass under an oak tree, dozing, with one ear cocked for a possible sheep-transporter pulling up to unload, as Vassílis had assured me they would. Several went by on the road, their double decks loaded with sheep, with the ponies and mules riding shotgun on the platform over the tailgate. But nobody stopped…

To pass the time I climbed to the fields above the town and gazed westwards towards Samarína, where the sinking sun glared sulphurously through gashes in the dove-grey cloud and the edges of the snowfields were modeled in silver-gilt. I wondered where exactly the route of the dhiáva ran, somewhere across those green valleys whose watercourses were punctuated by poplars.

In the morning we left promptly as arranged. The taxi-driver was in more amenable mood, although I still had to listen to a litany of anti-Vlach calumnies and townee’s scaremongering about how fearsome life in the mountains is: how the Samariniotes are all liars and how in the war they were traitors, showing the Italian invaders the way, until our boys stopped them at Stavrós — completely overlooking the fact that they had served in the army like all other Greek citizens.

“And where will you sleep? You’ll be cold. And if it rains? Snows? What about the wolves? Aren’t you afraid? Just last week one ate a man and his son when their tractor broke down. And the bears? And how will you find the way? There’s nobody there. The paths are all overgrown with branches. . . .”

…At Polinéri we left the asphalt behind. We were climbing truly now. We crossed the river where it squeezes between the great rock jaws of Aetiá and climbed again, up slopes of rock and coarse grass, through stands of thick-barked, straight-limbed pines to Filipéi, the last village before Samarína. I got out. I was pleased, because I wanted to walk and had saved 1,000 drachmas. The taxi-driver was pleased because he had avoided the slowest and roughest part of the journey.

Sadly derelict only a few years ago, Filipéi, like many of the higher Pindos villages, is enjoying a new lease of life. People who had left to seek fame and fortune in the cities are returning to build summer homes in the ruins of their ancestral hearths. Unfortunately, they prefer to build from scratch with breeze-blocks and factory tiles rather than restore the fine stone houses of their forbears, most of which are in a parlous state of disrepair, when not reduced to a heap of rubble from which even the timbers have been taken for firewood.

As a sign of the times, right beside the track, a New Wave Vlach was building an inn with restaurant and disco. I went in for coffee. A stuffed eagle spread its dusty wings in a corner and a bear was pinned to the wall, both protected species now. The ancient mother was swabbing the floor, grumbling at an even more ancient father in Vlach homespun, who complained of his rickety joints, stiffened by a lifetime on the open mountain. The entrepreneurial son appeared, bleary-eyed, in a tracksuit, and grumbled at both. His temper improved as he gave me a guided tour and talked of his plans to increase the number of rooms. He had chosen to stay, he said, because he liked the mountains, enjoying the quiet and the solitude.

He led me out on the terrace to show me the way to Samarína. The air was sharp and our breath showed, though the sun was well up, in a blue and rarefied sky. The altitude was around 1,400 meters. At our feet the ground fell away steeply to the river. That was where the old route to Samarína ran, along the riverbed and up the slopes to the col of Stavrós that closed the head of the valley to the west. Rising behind it, the snowy crags and peaks of Mt Smólikas burned intensely against the sky. To the south, opposite, the benigner slopes of Mt Vassilítsa were white too, well down into the upper edges of the beechwoods. Smíxi was there, only an outlying chapel visible, the main cluster of houses hidden by the intervening ridge.

As I had the whole day ahead of me and had never been there before, I decided I would go via Smíxi. I set off down the valley side. The new grass was fresh and tender underfoot; the blossom of wild pears was breaking into white. It was warm and sheltered in the valley bottom. A tiny whitewashed chapel basked half in sun, half in the shade of a scaly old plane tree on the bank of the river. I splashed across, the water glinting and sparkling in the direct path of the sun, and started up the opposite bank through oak and Black Pine and damp grassy clearings full of hellebores and the red-purple spikes of marsh orchids, where great lumbering tortoises were tasting the goodies of spring after their winter sleep. At the top of the slope an open meadow straddled the ridge. A cold wind blew and the grass was thick with primulas and purple and pale yellow orchids. I could see the houses of Smíxi opposite, spreading in a wedge from the bottom of Mt Vassilítsa’s girdle of beech.

I started down. On this side the trees were silver-barked White Pine, huge and leaning, with branches layered like cedars. I stopped for breakfast in the shade of one and washed my feet in the ice-cold stream that ran at its foot. There was a colony of Lizard Orchids on the opposite bank, unmistakable with long wriggly pennants protruding from their greeny-purplish flowers. The pine needles were soft. The air was warm again. Liver-brown cows snoozed in the meadow below the village.

When I reached it, I regretted having stopped to eat. The first building I came to was the magazí, where wreaths of smoke and the spitting of fat announced the roasting of a lamb. A group of villagers up for the weekend were enjoying the sun on the terrace; most of the village was empty still.

“Come in. Sit down. Have a drink and a snack,” they called as soon as I appeared.

I had a bite of lamb for form’s sake and went on my way.

It took an hour and a half to reach Stavrós, climbing steadily through pines, then beech, whose new lemon-green foliage was as translucent as onion skins. The weather had spoilt. Cloud had moved in round the peaks and the wind blew stiff and cold, pushing against me. But it was exhilarating to catch my first glimpse of Samarína, gathered like a distant flock of sheep on the lower slopes of Smólikas. It is the view that has excited generations of Vlachs: the moment of homecoming after a long winter in the alien plains. An iron cross marks the col, where a rough track passes now. Looking back, I could see all the country crossed by the dhiáva as far as the mountain overlooking Dheskáti and, beyond that, the white peaks of Olympus apparently floating in the sky.

The col of Stavrós is the watershed. To the west the rivers flow into the Aöós and out through Albania to the Adriatic. Just below the col is a spring and drinking trough and here the old kalderími [cobbled mule road] begins, cutting downhill through meadow and pine at a steeper angle than the modern track. The cobbles do not show for a while, but when they do they form a beautifully even roadway about two meters wide, cross-ribbed on the steep sections to give purchase to slipping mule hooves. When it was first built, no one seems to know; perhaps in the eighteenth century, which seems to have been the heyday for Samarína, as for the other Vlach communities of the Pindos.

Before that time, or at least prior to the Ottoman conquest, it seems likely that they were little more than impermanent summer shepherd camps. As Tsiógas said to me once, explaining the origins of Samarína: “The first thing was the need for food: the milk and cheese and meat of the flocks. And the wool for clothing. But the flocks needed food too, so they came up to the mountains in summer, where there was grass and water. Maybe at first it was just one or two families, brothers and relatives together, like us. And then they would group together with other families, for strength and company, and these bigger groups, in turn, created new needs: for saddlemakers and cheesemakers, cutlers and muleteers. Gradually they formed together into a village. You can still see the ruins of smaller, older settlements around Samarína, at Skordhéi and Garélia.”

Then, with the coming of the Ottoman conquest and relative political stability, a period of great prosperity began. The enjoyment of a privileged tax regime, granted in part because of the Vlachs’ strategic position astride the mountain roads and passes, led to the creation of a merchant class and the gradual extension of Vlach commercial interests throughout the Balkans and as far afield as Russia. Bulgari, for instance, one of the world’s leading jewelers today, began life in Kalarítes, once one of the richest Vlach villages of the Pindos. A memorial in the village square commemorates fifteen native sons active in the struggle for the liberation of Greece in the first years of the nineteenth century. Their places of residence alone — Venice, San Severo, Naples, Odessa, Vienna, Bessarabia and Romania — testify to the far-flung reach of Vlach influence.

* * *

[Salmon is speaking with an old man, Barba Anastássios, in Samarina:] I told him what the taxi-driver had said about the Samariniotes acting as guides to the Italians.

“It was about this time of day they came,” he said, “on an autumn evening in October 1940. I was sitting here. There were about thirty people in the village. The flocks had gone. They didn’t hurt anyone, but took two men to show them the way. `Grebena, Grebena,’ they kept saying. They couldn’t say Grevená. But they didn’t want to go via Stavrós, because our artillery was up there.”

“But why do the plainspeople say such things about you, that you are the sixth tribe of Israel and so on?”

“They don’t like us because we are first among the Greeks. We are the pure Greeks.” And he repeated the theory about the Vlachs being indigenous inhabitants of the Pindos trained by the Romans to guard the road to Byzantium. “And we sent help to Missolóngi, as it says in the song, Ta Pedhiá tis Samarínas. We sent thirty tough warriors to the Balkan wars. The Turks never set foot here. They are jealous of us, they don’t like our independence. They can’t understand our language. We were a civilized people when they were still Turkish serfs.”

“What about the Roumanian connection?” I asked.

“We’re not Roumanians. There’s no connection. That was that crazy fellow, Dhiamantís.”

“I suppose marriage was another thing. I mean, in the old days, you only married among yourselves, didn’t you?”

“We neither gave brides nor took them,” he said.

Another old man came up to us, whom Bárba Anastássios did not recognize, and introduced himself as a Vlach from the Aspropótamos.

“You see, we don’t even understand each other,” Bárba Anastássios said. “We have different words and accents. And we are both Koutsovlachs. The people from Foúrka — you know Foúrka, the village over the mountain — they are Albano-Vlachs. They used to go down into Albania for the winter.”

* * *

…What makes Great St. Mary’s [Church in Samarina] renown more than anything else is the pine tree that grows from the roof of the apse. It has been there as long as anyone can remember without ever growing any bigger or producing a cone or even showing any evidence of roots either inside or outside the wall.

The glory of the church, however, is the interior, where every available space is painted with frescoes illustrating the lives and gruesome martyrdoms of the saints. The style is softer and more naturalistic than the harsh asceticism of earlier Byzantine schools, though the influence is clear. The colors are fresh, with reds and blues predominating. The artists were locals. Indeed, Samarina was home to a school of church painters from the eighteenth century up until about 1900. There are examples of their work — they always signed it — all down through the Pindos as far as Agrafa. They were not great artists, but lively skilful practitioners of a truly popular style, a rustic equivalent of the bande dessinée. They went for the lurid and sensational: soldiers hacking and carving babies in the Massacre of the Innocents, tearing the suckling babes from the embrace of their anguished, prostrate mothers. All shock-horror stuff, with a superlative in every line. And flattery for the nobs: with portraits of the church’s benefactors got up as saints on the north wall. And any surface that does not lend itself to narrative painting, like the window reveals and the intricate wooden ceiling, is decorated with abstract motifs. Not an inch is left unpainted.

In addition to the painting, the other great opportunity for showing off craftsmanly virtuosity in the mountain churches is in the iconostasis, usually a great wooden barrier three to four meters high stretching the full width of the church in front of the altar. Great St Mary’s is made characteristically of box wood, carved with figures and scenes in full relief. The broad central band of the iconostasis is set with icons of the saints, with illustrative scenes from their lives carved below. For example, the Annunciation and the Flight into Egypt are represented in the space beneath the icon of the Virgin, which occupies the place of honor beside the sanctuary door, since it is her church. The space below the icon of John the Baptist shows a soldier dressed in a foustanélla — the mountaineers’ kilt — and wearing Vlach mustachioes severing the saint’s head at the behest of Herodias. A lower band illustrates the Last Supper, the Temptation of Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, while the vertical divisions of the iconostasis are formed by hollow columns of flowers and foliage coiling upwards from wooden vases, interwoven with representations of wild goats, birds, deer and lions. The bishop’s throne and the pulpit are similarly worked, the latter a three-meter ice cream cone supported on the shoulders of a bow-legged angel, also dressed in a foustanélla, as if the Vlachs could not envisage a heaven peopled by anyone but themselves.

Musician at a Vlach festival (panayiri)

The whole building is in desperate need of care and attention. Fragments of fresco drop off under the action of the damp, only to be patched with cement. The woodwork is rotting. And there has been some crazy talk of cementing over the flagstone floor to make it easier to clean. Facing the church across the green is the now defunct school. It used to operate in the summer months, when the families came up from the plains. I have heard it claimed that the Vlachs’ superior brains — like the Welsh in the London teaching world, lots of them have made successful careers in the academic world and other professional occupations — are the result of the extra teaching they received in these summer schools, when the rest of Greece’s child population was drowsing in the heat.

* * *

[Salmon relates his first visit to Samarina, on August 15th, the feast day of S’ta Maria:]

There were cars parked all the along the track into the village. Itinerant tradesmen had set up stalls selling sweets and corn on the cob and trinkets. The square was tight as a rush-hour lift. Noise and good humor were the order of the day. Shepherds mingled with lawyers and bourgeois ladies from Athens. There was no social holding back, no class consciousness. If anything, the shepherds held the post of honor, for they were the true Vlachs, the guardians of the flame, without whom the BMW-drivers from the cities would have no roots to return to.

In every ramshackle yard new-slaughtered sheep’s carcases swung by the heels from hook and branch. Flies buzzed round the drying gore. Grandfathers dipped bloodied arms into slit bellies and hauled out bags of blue-grey guts.

“Come in,” they would say. “Come and drink a tsipouráki. Sit down. Where are you from?” Most of them had had a few themselves.

“What? Only strangers get something to drink?” an old chap complained when the dark-haired jolly woman of the house poured me a shot.

“Finish your work first,” she told him. He was gutting a sheep. And, turning to me, she asked, “Koum khi? Gíne?”

I looked blank, and the old man said to her in Greek, “He’s not a Vlach. He’s a foreigner.”

She laughed. “They were all talking Vlach and I thought you were one of us.”

* * *

We returned to the stroúnga about four o’clock. Karás, the pony, kept stopping for breath on the way up and I had to straighten his load.

“Tórna, fráte, tórna. It’s turning, brother,” Vassílis said, reminding me of the story I had told him about the Vlachs’ first mention in recorded history, in a Byzantine chronicler’s account of a sixth-century battle. That was in 579 AD: the Byzantine general, Commentiolus, was in pursuit of the Avars, when his Greek-speaking army, misunderstanding the language of its Vlach muleteers, suddenly turned tail and fled. One of the muleteers, seeing his companion’s load slipping, had called out in warning, “Tórna, fráte, tórna,” which the surrounding soldiery misinterpreted as “Turn back, brother, turn back!”

* * *

We ford the river by the Dúe Kiátra, the two rocky heights that close this part of the valley and strike up the slopes opposite by the vestiges of the old mule road. At the top of the climb we come out on a grassy ridge, pitted still with Civil War dugouts, with the villages of Ziákas and Lávdha off to the south and the road to Avdhélla and Perivóli. But we have seen the last of Vlach territory and the high mountain country now. The people who live in these villages are known as Kiupatsharéi. From here on oak supersedes pine and we’re among strangers, Greek-speakers, who regard us with suspicion. For, like gypsies, nobody knows where we come from or where we are going…

The night is cloudy and there are few stars. The shepherds get little sleep for fear of wolves, and there are numerous alarms, the sheep stampeding with a sudden whirr of feet and the dogs rushing off furiously into the woods…

Dozens of flocks used to camp here, and mule caravans as well. It was particularly crowded because Mustafá to Ziákas was a common stretch of road for all the Vlach villages.

“They got caught in a terrible battle once,” Tsiógas said. “Around 1880. The old people remember it, from their parents. It was at Filioúryia. We’ll go by there ourselves in a few days. There were lots of dhiávas traveling together accompanied by the kapetanáta (bands of irregular warriors) for protection against the robbers who used to try to hold them up and take their money. They were dangerous times.

“There’s a little chapel at Filioúryia. They were all camped round about when an army of Albanian Turks fell on them. It was not just the shepherds doing the dhiáva then. There were all the other workers and their families: blacksmiths, cobblers and so on.”

“There was great slaughter,” Tsiógas continued. “There’s a song about it.” And he began to recite: “Trees, don’t put forth your leaves. Flowers, do not bloom. . . . The Vlachs will not be coming this year.”

In fact, many of them never came again. For to avoid the dangers of the frontier zone and the difficulties entailed by having winter and summer pastures in different states, they migrated south into Greek Greece and made new villages there.

Yiánnis has fashioned a wooden spit for our use and we use it to roast kebábia at the fire.

…Another misty morning. We’re heading down a long wooded valley. Again I am alone, putting my trust in Vassílis’s directions. I’m following the crest of a ridge. Cyclamen and crocuses bloom in profusion among the crisp layers of fallen oak leaves. I can’t see much, but I can hear the reassuring sound of Tsiógas’s bells below me.

Gradually he works his way up to join me and we saunter along a faint trail on the ridge top with the sheep following in line astern. He walks with a slight swagger, his crook across his shoulders like a milkmaid’s yoke, hands hung loose-wristed over the ends. In reply to my landlubber’s questions about where exactly the vlakhóstrata ran, he replies with some exasperation: “It’s not a road, Timi, but a direction. Only in restricted places, like Ayii Theódhori, where there isn’t any other way. We learnt it from our fathers.”

…A few minutes later the dogs assaulted another local, a scared old fellow with only one arm. “Do they bite?” he asked, as I rushed to rescue him too, thinking this canine aggression was bad publicity for us. Tsiógas’s only comment was, “It’s not worth chasing after them. You tire yourself out and it only encourages them if they think their masters are with them.”

I think he got some satisfaction from seeing the dogs have a go at the despised kambísii [lowlanders]. For although the Vlachs are accustomed to considering themselves the aristocrats of the mountains, I think they are more than a little narked that these ignorant plainsmen, erstwhile Turkish serfs (“Not even a teacher did they have, do you hear?”), should have ended up more prosperous than themselves.

…A tractor was ploughing not far away. At the end of a furrow the driver got out and shouted at me: “Re, patrióti! Hey, you, fellow-countryman!”

It was not a friendly greeting. I ignored him and sat down behind my animals. When he shouted again, I yelled, “Ask my mate!”

I heard him shout at Tsiógas: “Are you passing through or are you grazing them?”

“What the hell do you mean?” Tsiógas replied, furious. “This is public land, as you very well know. You’re illegal. You’re not supposed to be ploughing here. We’ve had grazing rights since before you people even came here and started chopping down the trees and grabbing common land.”

By “you people” – and he certainly intended it in a derogatory sense — he meant the Póntii, the descendants of the old Greek colonists of the Póntos or Black Sea, who had been repatriated to Greece as refugees in the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in the aftermath of the Asia Minor disaster in 1922. Many of them had been given land in western Macedonia.

* * *

It begins to sleet. By the time we reach the beech woods the sleet has turned to snow. We’re partly protected under the trees. It’s like walking through a huge cathedral of color. The ground is burnished copper; the roof of foliage, green, gold and red. The light within is a sort of glow as if lit through glass. The dogs push ahead, hunting, scenting quarry. We follow slowly, part of the time on the old mule road, part of the time on a forest track.

I say to Tsiógas, “Do you think archaeological digs on dhiáva routes would produce anything?”

He said some had been done. “But Vlach artefacts have always been made of wood. They would disintegrate in the earth.”

I said, “How long do you think these trails have been walked by Vlachs?”

A thousand years, for sure,” he said, “maybe more.”

An idea which I find very moving: the map of these unmapped places carried only in the heads of the Vlachs, each one knowing only the way from his winter quarters to his summer pastures.

* * *

A neighbor’s truck is coming down the track. He has driven down from Samarína. His headlights are swinging and dipping all over us as he turns across the grass towards us. We climb in beside him. “Did you have a good time?” he says, grinning. “Now you really are a Vlach.”•

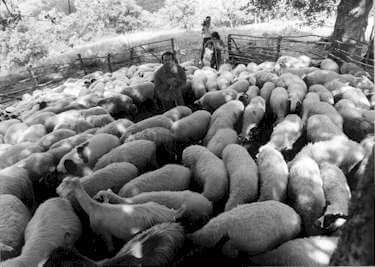

What it’s all about: Shepherd & sheep in sheepfold (cutaru)

Responses