The Mighty Water-Wheel

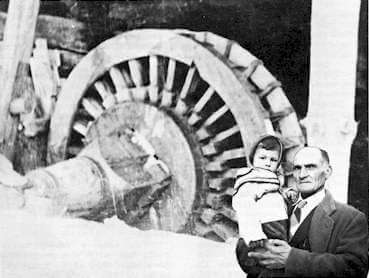

This is the giant water-wheel which transformed the rushing cold water of the mountain stream into mechanical energy which in turn powered the sawmills and flour mills of Baieasa. Please note (p.14) the geometrical perfection of the wheel, which involved many complex principles of applied geometry. At a glance it seems to resemble a huge sunflower with its enormous hub at the center and spokes, reinforced by wedges, radiating gracefully outward. Technically speaking, it is known as an overshot wheel, which means that the jet of water would strike it about one o’clock and cause the wheel to rotate, transmitting power to the shaft of the wheel which would then use a cam to move the saw up and down, cutting the log and producing the boards. This arrangement is known as a reciprocal saw.

Baieasa was known as the lumber center throughout the Zagori (a name derived from Slavic, meaning “behind the mountains”), and after the lumber was cut it was stacked to dry and finally transported to its destination by pack mules. It was a sight to behold: these small creatures loaded down with long boards lashed to both sides of a specially built wooden saddle. Most of the lumber was pine with a sprinkling of hard wood. Knotty pine was available in abundance and very popular because it could be used for many purposes in interior and exterior construction. The interior of Vlach homes, including even the ceiling, was generally finished in knotty pine. It was a joy to enter a Vlach household, always well-scrubbed by the women, to smell the masculine perfume of the mountain pine, and to take in the bright, warm colors of the vilendzi (heavy woolen blankets) spread on the floor and covering the wooden chests lining the walls.

The designer and builder of this water-wheel was my father-in-law Nicolai Brajituli, the well-known engineer and millwright of Baieasa. He appears in my photomontage, holding one of my sons in his arms. Brajituli was a mechanical genius whose services were very much in demand throughout Epirus, where he had built many sawmills, flour mills, beetling and fulling mills. Whenever he was contracted to build a mill, he was provided lodging and food by the contracting party and treated with respect and even reverence; he was addressed as “master.”

Nicolai Brajituli did not hold an engineering degree. He attended neither MIT nor any Greek polytechnical institutes. He never studied physics. He never studied hydraulics. His education consisted of about four years of elementary schooling with the usual beatings and ear-pulling by some tyrannical teacher.

He used a few primitive tools but with a sophisticated knowledge. Many of his tools were made by the local blacksmith. Generally he by-passed the drawings, preferring instead to work out the details in his mind. His principle tool was the skipari. I don’t know of a good translation in English; a tool known as an adze, which has a curved blade at right angles to the handle, approximates the description of a skipari. The good skipari came from Germany or England and were the pride and joy of the masters who used them.

Although the local blacksmith was not involved in the manufacture of precision tools, he did, however, contribute significantly to the construction and maintenance of the various mills. He made the axes that felled the trees, as well as some of the metal parts used in the mills.

I believe that designing a sawmill or a flour mill and building every part from scratch was a phenomenal accomplishment. Try to imagine a modern engineer setting up a small factory by making every unit by himself and then assembling them. He would not be likely to make things; rather, he would probably buy the required engines, gears, pulleys, shafts, belts, etc., and assemble them, with the help of many people. First, the millwright had to choose the location of the mill. This depended on the availability of water power and proximity to a supply of raw materials: trees. Logs are hard to move by sheer manpower. There were no tractors. Moving logs was an arduous and dangerous job — there was always the possibility of being crushed or mutilated. In the case of a broken leg or other severe injury, there was no doctor around.

Another engineering feat associated with all water-powered mills was the design and construction of the sluiceway, an artificial channel to conduct the water, complete with valves or gates to regulate the flow. It was built with planks and a staging which supported it. The building of the sluiceway, over rugged terrain and considerable distance, was considered almost as difficult as building the mill itself.

In addition to building sawmills and flour mills, the millwright was called upon to build two other machines, the mandani or batteala (beetling mill), used for softening woolen fabric, and the drashteala (fulling device), which made the fabric fluffier and tighter. The mandani was the more colorful; it consisted of four huge wooden hammers or mallets that were raised by the turning water wheel and its cam. The mallets would beat slowly in a pleasant, muffled rhythm that could be heard day and night for weeks at a time. It was the pulse beat of the village. We children loved to stand near the mandani, but we were also afraid of these powerful hammers when we considered what would happen if we fell into the machines and were beaten to a pulp by them.

The drashteala was the least complicated of the Vlach water-powered machines. It was merely a huge cone made of planks fitted together in the same manner that a cooper makes a barrel out of well-fitting staves. The small portion of the cone is embedded into the ground. Water from the sluice would hit the drashteala at the perimieter, causing the water and blankets to whirl round and round; the vilendzi would emerge days later, fluffier and smoother. There were no moving parts.

Conclusion

Modern tools, new sources of power, materials, and techniques have changed everything today. Gasoline and diesel engines, welding torches, chain saws, and other power tools are the death knell of the ancient crafts and highly developed skills of the old masters. The engineering skills of Nicolai Brajituli and other self-taught experts will not be passed down but will dead-end in the masters’ graves. Many crafts practiced by Vlach women, such as weaving and embroidery, will also disappear. The mighty water-wheel, turning and splashing clean white water in every direction, will be replaced by a powerful but foul-smelling diesel engine. And before too long, our dynamic, musical, earthy Vlach language will no longer be heard in our beautiful mountain villages.

We elders must jot down every bit of knowledge we have of the past, in order that our descendants will have some idea of what Vlach civilization was like before it disappeared.

Responses