From the Editor — The Failure of the Ethnic-State

Not long ago I attended a lecture about Woodrow Wilson and his support of the right of ethnic groups to have their own states — a principle that falls into greater disrepute with each new atrocity committed in its name. At the lecture’s end, a bow-tied professor with an elegant accent arose and said, “Yes, a lot of terrible crimes have been committed in the name of national self-determination — but it builds states, and anyway, what is the alternative?”

I wanted to shake the man and say, “You’re standing in it!” There is an alternative to the tribalism that is rending the world today. It’s obvious — perhaps a little too obvious. It’s called the American Way, and it’s one of our greatest contributions to Western civilization.

During the Enlightenment, educated western Europeans felt they had rid themselves of a kind of tribalism by rejecting the deep religiosity of the Middle Ages. But they merely ended up trading religion for nationalism. You can deplore the blind faith of medieval society all you want and cry out against the barbarism of Crusade and jihad alike but the simple truth is that nationalism is the most destructive force in human history, having killed 75 million human beings between 1914 and 1945 alone — and it just keeps on killing.

Among the strains of nationalism that have appeared in the world is one mutated form, the American version. It is almost unique in that it is not based on ethnicity but citizenship. “The adjective `American,'” writes historian Michael Walzer, “points to the citizenship, not the nativity or nationality, of the men and women it designates. It is a political adjective… It never happened that a group of people called Americans came together to form a political society named America. The people are Americans only by virtue of having come together. And whatever identity they had before becoming Americans, they retain.”

The idea that the people who constitute a nation ought to be of the same ethnic group originated around the middle of the nineteenth century in Western Europe, where it prevailed over the notion of citizenship as the common bond. Perhaps this has something to do with America having been an amalgam of ethnic and religious groups from the start, while most Western European states were dominated by one or another group. Whatever its genesis, the ethnic-state has been a disaster.

The American citizen-state was strong enough to stay together despite a Civil War with Southern separatists; if coming together as a nation was the act of all the people, then it followed that there was no right of unilateral secession — the dissolution or dismemberment of that nation also had to be agreed to by all the people. On the other hand, the European ethnic-state has left itself open to secession and subdivision when rival ethnic groups claim the right to self-determination — a notion reinforced after World War I, when Woodrow Wilson championed that right for every “nation or people” (in practice, every ethnic group).

It is utterly ironic that a President of the United States should have supported so un-American a principle. The irony was not lost on Wilson’s Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, who saw unqualified self-determination as a concept that was at best inconsistent with American practice, at worst “loaded with dynamite.” But he was overruled and ultimately dismissed by the President; ethnic self-determination was enshrined in the settlement of World War I; and while some Western European nations have since moved away from the ethnic-state model, the concept of self-determination has gone on to dissolve colonial empires and multiethnic states throughout the rest of the world.

The problem is not really the right of self-determination but who has it. It is an individual right of the citizens of a state, not a collective right of groups within the state. Our system is based on a covenant between the individual and the state. “A mature nation such as Britain or France is in reality a melting pot of races and cultures, held together by common allegiance to political structures and traditions,” writes Jacques Attali, former President of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, who also notes, “Such structures and traditions are either absent or barely developed in Eastern Europe.”

In all fairness to the people of Eastern Europe, Western countries that have moved to some degree beyond nationalism are not necessarily their moral superiors. Indeed, non-Western countries learned about nationalism from the West, and out of necessity. Ethnocentrism is like a powerful weapon system: once one country has it, others feel a need for it as well — a trend that has helped fuel our current worldwide escalation. Once Serbian nationalists, for example, start oppressing their Albanian minority, there is not much left for the Albanians to do but to ratchet up their own nationalism, and so on. It is perhaps natural that the response to collective oppression is a demand for collective rights. But it would be misguided to discourage the latter without also discouraging the former.

It is high time we admitted that absolute self-determination has been an absolute disaster, to this very day. Germany precipitated the Yugoslavian catastrophe, for example, with its pressure for premature recognition of Croatia and Slovenia. Why do we automatically assume that ethnic groups would be better off in their own states? Only because they are so often mistreated in states dominated by other ethnic groups. The truth is, if individual members of minorities are accorded the full panoply of human rights, there should be no reason for them to secede.

Today in Bosnia and in many other countries throughout the world, the failure of unqualified self-determination can be measured in grave markers. Our support of this misguided concept dates from a war that began in Sarajevo in 1914; perhaps the mass carnage in Sarajevo in 1992-94 will help bring us to our senses.

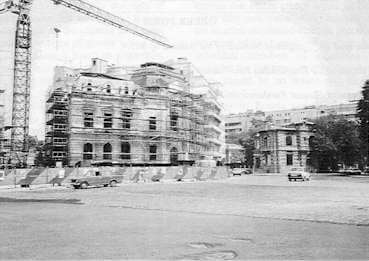

Scene from Bucharest after the Ceaucescus.

“The man of archaic cultures tolerates ‘history’ with difficulty and attempts periodically to abolish it” -Mircea Eliade

Responses