Ethnic Values & Ethnic Identity

America as a pluralist society fosters ethnicity, and Americans often maintain their ethnic identity for the sole purpose of group identity. How we live, both mentally and socially–even how we survive — is often determined by who we think we are.

The fact that we Aromanians exist as a group is illustrated by our participation in this Society and our interest in maintaining a shared cultural tradition. As a group, these shared traditions are precisely what make us Aromanian and they contribute to our perception of who we are.

What do I mean by shared traditions? No doubt the first thing to come to mind are practices such as the coin in the pita on New Year’s Day or the red and white string worn for the Ides of March. These practices are rituals, however, and by no means do they constitute the only basis for our social relations.

Shared traditions are rooted in the symbols, values, and norms which keep people either out of or in the group, thereby maintaining a group boundary. Let us examine how Aromanian values have been integrated into the ethnic process, providing the foundation of Aromanian ethnicity, and also how we, as Americans, survive as an ethnic minority in this pluralist society among a variety of ethnic groups, speaking a new language, changing our mode of dress, and even marrying outsiders without succumbing entirely to the assimilation process.

Like so many other ethnic groups, we Aromanians have never established our own nation-state. Therefore, our survival as a group relied heavily on the establishment of group boundaries rather than political boundaries. These boundaries were portable and accomodated well to the pastoral mode of subsistence of the Old Country as well as to the capitalist mode of the New World.

As one elderly Aromanian told me, “We raised mostly sheep, horses, and goats. That was our trade. We used to travel from the north in the summer to the south in the winter. We never were farmers. We were proud of our trade because other people needed us. They needed our milk, wool, cheese, and rugs. They were a necessity. We never wanted to be farmers and raise wheat because the farmers were peasants. We were on a higher level and we kept ourselves there by being shepherds.”

Few, if any, Aromanian-Americans are shepherds, but the values which emerged from the pastoral mode of subsistence provided the foundation for Aromanian identity. For example, their desire to remain economically and socially independent and mobile: In America, this predilection is best evidenced in their pursuit of entrepreneurial ventures. For many first-generation Aromanians, this meant opening restaurants, barber shops, and other service businesses. For the second generation, it meant becoming doctors, lawyers, educators, industrialists, and other professional ventures. But the bottom line is there: a preoccupation with “being my own boss, being independent, others needing me and my services. The ability to go where I want to go, when I want to go.”

The values of honor and pride are also significant components of the Aromanian value system; these values are maintained primarily within the social unit of the family. Often the phrase, “Oh, he/she is from a good family,” is overheard. But what does “good” mean and, more importantly, why does such a phrase echo even to this day in America?

In the pastoral society, the family provided the basic social and economic unit in an area of limited resources. “Shaming the family” often meant removal from the group, therefore reducing the family and its association with other families.

“We never married different nationalities. We would stick with our own people. Even closer: Very few people even went out of the town to get married. It was shameful to marry out of the group.” The fact that the family was shamed when a member married outside of the group served a vital purpose toward maintaining group identity in the Old Country. In America, however, where intermarriage is common, honor and pride associated with marriage still prevails in the Aromanian value system: Occupation, family history, industry, commitment to religion are all criteria for evaluating a potential spouse and determining family position within the ethnic community and so providing a guideline for group stratification.

A key element in the survival of this group has been its ability

to adopt social and cultural patterns of other groups

when its own survival has been threatened.

A final outcome of the pastoral mode of subsistence was the development of ingroup/ outgroup identity mechanisms and their integration into the Aromanian value system. A key element in the survival of this group has been its ability to adopt social and cultural patterns of other groups when its own survival has been threatened.

This mechanism includes terms of reference, language, and other cultural patterns. For example, when someone asks you your nationality, how often have they assumed you were Greek, Macedonian, Romanian, or Albanian? Also, we are known by a huge variety of names, including Vlach, Tsintsar, Koutsovlach, and others.

“If I said I was Aroman to a Greek, he would not understand. He would say we were Vlach because that is what he knew us to be. But to ourselves, we always said we were Aromani, that’s how we knew each other. We’d say, ‘Eshti Aroman?’ and he’d say ‘Mini escu Aroman.’ That’s how we knew each other. But the Greeks, Albanians, Turks, they didn’t know us that way. It was like our code.” Ingroup/outgroup terms of reference provided a vital boundary mechanism for group solidarity, an identity mechanism which continues to this day.

Language has also been an important component of this on/off mechanism. Multi-lingual abilities were common among men who were required to conduct business or other negotiations with outsiders. In Europe Greek, Albanian, and Turkish were common second and third languages spoken exclusively outside the home, often to camouflage group identity from outsiders. This pattern continues: Despite the fact that the mother tongue has largely been replaced by English, we often hear the native tongue spoken in community settings. It is used equally for restricting group membership.

Where did we come from and how is it that we have survived as an ethnic group? The Aromanians are basically an ethnic minority transplanted from Balkan mountain communities to American industrial cities. Our value system is rooted in the pastoral mode of our forefathers, a mode encouraging independence, industry, commitment, mobility, and religious faith. All of these are cultivated in the family, the major social unit encouraging a sense of honor, pride, and prestige amongst its members. All of these values are shared by the group, and the group reacts whenever any of its values are violated.

Be advised that we are here today having survived centuries of domination and oppression. To those who believe we have assimilated and that group extinction is imminent, I remind you that the key word here is process. The physical world is not static, nor is the social world. An ethnic group that wishes to survive must accomodate change. Change is an outcome of this process and we continue in the midst of it, so highlighted by our ability to evidence or camouflage our ethnic identity according to both the surrounding circumstances and a value system which has evolved from a physical and social setting of continual strife and domination.

Who are we? We’re Aromanians. Be proud of it, because that’s what the value system advises. If you do, chances are you’ll have less difficulty surviving.

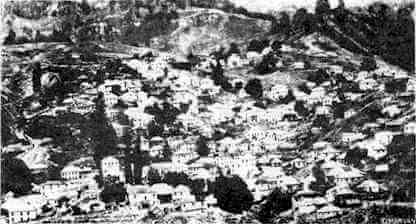

1927, 22 Sept.

The village of Ardhella, high up in the Pindus Mountains of Greece.

This photo was taken in 1927. During World War II, Ardhella

was burnt by the Germans, but it has been rebuilt recently.

The article on our ethnic heritage is very interesting and informative. I am proud of that heritage, and that we

have the Society to keep us informed and connected.