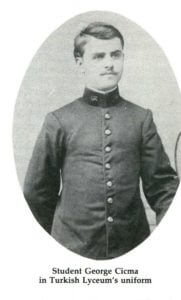

Haralambie George Cicma Autobiographie part IV

A Vlachs’s Life in His Time

(Continued from last issue)

In an attempt to avoid a confrontation with Uncle Dimitri regarding my feelings towards Pusha, as well to avoid family pressure to choose Maritsa, I decided to spend the 1912 summer vacation at the Lyceum. Ten days into my vacation, I was aston- ished to see Uncle Dimitri; he was on his way to Constantinople on government business, and stopped at the school to see me. He was advised about my excellent marks from the administration office and he gave me money for incidental expenses; he also insisted that I return at once to Turia-Kragna. I had never disobeyed a direct command from him, so I packed my trunks and was again escorted home.

They received me cordially and for the next two weeks I had a grand time-no one mentioned Pusha. My Uncle returned and invited me to his house; he was sitting in his favorite place under a large pear tree in his garden and, unknown to me, his wife and Maritsa’s mother were concealed nearby.

He received me with many compliments and much pride, stating how happy he was to have someone who would be able to take his place in the government when he was no longer willing to be so actively involved. Soon he began to tell me that I was growing older and he felt that it would be suitable, at this time, for me to become engaged to someone. He suggested, delicately, that he had heard that I was in love with Pusha and that, moreover, Maritsa looked on me with great favor. Maritsa, he argued, was much more beautiful than Pusha and obviously she was a much more suitable match for me. However, he said that he did not wish to choose for me but felt that I should definitely decide to marry (become engaged to) one or the other before it was time for me to return to school.

I refused to make any choice nor would I say which I preferred. I did not dare to say anything. He advised, not disagreeably but in a fatherly manner, that Maritsa could help me far more than Pusha could—both in social position and financially. I then argued that I had no desire to become engaged while I was still attending school and so could not and would not accept or refuse either girl.

Dimitri finally lost his temper, he informed me angrily that he had a number of letters written by me to Pusha and told me that I must make my choice immediately as I was not being fair to either of them. I again refused, I realized that he was trying to find out whether or not I was really in love with Pusha—I was not ready to make that statement.

Uncle Dimitri then issued his ulti matum, I was to marry Maritsa; even if I had chosen Pusha, he would not have given his consent. He also threatened that if I refused to accept Maritsa, he would take me out of the Turkish school and would have me persecuted in every Turkish-ruled territory in the world. I remained silent. “If you are to live under my guardianship, you must accept Maritsa. Moreover, your engagement will be announced and the half-marriage ceremony will be performed tomorrow night,” he was making certain that no further complications would arise.

It was so decreed!

Accordingly, the following evening, my step-aunt and Maritsa’s mother served a great feast at my home; unknown to me, the family cooks had been preparing food for this celebration all the two preceding weeks. Many government officials and relatives were present, having been notified weeks before!

The priest performed part of the marriage ceremony over Maritsa and me; after this rite the soldiers fired their pistols and fireworks, which Uncle Dimitri and his friends had brought from Constantinople, were set off to celebrate this, supposedly, happy event.

A regiment of soldiers stationed at nearby Ciprie heard the shots and, believing our town to be under siege by the guerillas, charged in full battle-dress across our vineyard to repel the assault; as soon as they learned the cause of the disturbance they were invited to join in the festivities, everyone was having a marvelous time. That is, everyone except me; my heart was heavy, I couldn’t laugh, smile, dance, or join in the singing. I didn’t even see the guests as Pusha’s face, her beautiful hair, sparkling eyes, her lips, all were before me, blotting out all else.

In her home just across the field, Pusha soon discovered the reason for the celebration. She sat all night on her porch, crying, all faith in me destroyed.

The first thing the following morning, I sent her a note telling her not to worry, I still loved her—if she would only keep faith and wait until I had finished school and secured my position in life; then cannons, not pistols, would be fired at our wedding!

I was most closely watched, all my actions must be accounted for, so naturally we had little opportunity to even exchange letters, only through my close friend John Barjuma were we able to communicate; he was deeply sympathetic and finally arranged a meeting between us at the home of his brother-in-law. Pusha and I had only a few minutes together, I reassured her that nothing could separate us forever and, although we were suffering now, she must believe in me and be courageous; then, with the help of God, we would more than make amends for this later. John, with his usual consideration, went into another room and for the last time in my life, I touched the sweet and lovely lips of my darling. It is impossible for me to detail the sweetness of that brief moment; what matters is that it actually happened, enriching my life. We never saw each other again but I still, without misgivings, remember her vividly.

My relatives did everything possible to try to make me forget my feelings for Pusha. There was no evening that my future mother-in- law failed to invite me to her house. Truly, Maritsa was beautiful, but she made no impression on my heart; she was rather bashful (perhaps she didn’t like the arrangement any better than I did) and, as I was only pretending to have any affection for her, I rarely kissed her, when I did it was only because her mother insisted on the demonstration!

Her mother would often chide me saying, “You don’t love my daughter, you still love that Pusha, no wonder you are not demonstrative. You’d better shape up and show me that you really love my daughter, don’t be so timid, give her a real kiss.” This angered me and I would tell her that she should not force Maritsa to act so common, telling us to embrace all the time.

Maritsa’s mother tros common, wealth or not; she frequently left Maritsa and me alone, an unusual procedure for our country. Naturally, I showed Maritsa every courtesy, but this mattered little to her mother; many times I arrived at their home and found Maritsa crying be- cause her mother had beaten her for not being more openly affectionate to me. I did admire Maritsa’s modesty but I detested her mother.

Looking back over the span of years, I think the emotion I had for sweet, misused Maritsa was that of a brother to a sister, I feared her mother, was acutely aware of her anxieties, wanted to help in any way possible, yes, it was definitely a brotherly affection rather than that which I should have felt for my fiancée.

All this summer I had a peculiar premonition that I would not have long to remain in Turia-Kragna. Almost every day the soldiers and I went to different mountains, plateaus and springs to revisit the scenes of my childhood. Profet Elie Shupitic was a beautiful spring between small hills, I had the soldiers fashion benches, clean brooks, springs were dug out, and a dancing pavillion was built, when completed it was picturesque and unique. We improved other springs, too, and each evening the students and soldiers would gather to tell stories, laugh, sing, and have fun.

In September my uncle and all my other relatives, as usual, accompanied us to the river bank. I hated to say good-bye to my mother and she must have felt, also, a vague warning of what was to come. I begged her to accompany me a little further but my uncle would not hear of it. He said that I was cruel and foolish and was trying to make my mother worry. I went on alone, full of the feeling that I had said my last good-bye to home and friends.

I resumed my studies, having entered the sixth year, things went along much as usual but toward the end of September we began to hear strange rumors about the Balkan countries declaring war on the Turkish Government. The students at Monastir-Bitola staged a violent demonstration against war but this really helped not at all—isolationism then was as useless as it is today. War was formally declared about the first of October, 1912 and all communications with Turia-Kragna ceased.

The Turks were attacked on one side by the Serbians, on another by the Bulgarians and by the Greeks from the south; all were striving to reach Monistir-Bitolia. The Khan (ruler-governor) of the city called an official cabinet meeting and, with his ministers, decided to open the gates of the city to the Greek Forces, without a struggle, prefering Greek rule to that of Serbia or Bulgaria. However, Gaevid Pasha, the General in charge of the city, declared Martial Law and undertook the defense of the city personally. With only a small force, he fought at Perlipe, a city not far from Monistir-Bitolia and held back the Serbians for two and a half months. The Greeks, all this time, were pressing towards Monistir- Bitolia, through Sarovilch. General Gaevid learned of this and he split his forces and defeated the Greeks at Florina, beating them so badly that they had to retreat to Salonica. This splitting of the Turkish Army gave the Serbians an opportunity to break through the ranks at Perlipe and, at about Christmastime, they entered our city.

While the war was in progress, I was serving in the Turkish Red Cross as did many other students at the Lyceum, our buildings were also used as a hospital. From the time that the Serbians conquered the city until the end of January, 1913, I was held as a political prisoner of war. We were not really mal-treated but there was very little to eat, I remember that someone killed and roasted a horse anyone who wanted some could have it but I could not bring myself to eat any. We were at last released and given visas to go to Constantinople with the remaining Diplomatic Corps members. Ended at last was our hunger, cold and, especially, the fear of being executed at someone’s slightest whim.

When I arrived at Constantinople, the custom inspectors opened every bag and package I had; they found several letters without stamps which I was carrying for some Romanian students, to be delivered to their families; as these letters were in a foreign language, the inspectors were certain that I was a spy and I was sent to prison.

Three or four hours later, I was taken to the office of the Turkish Inspector-General; as soon as he had read the name “Cicma” on the report he was anxious to see if I was a relative of Dimitri, whom he knew well. They brought me to his office and he asked my full name and hometown; as soon as I said Turia-Kragna, he rose and asked me if I was related to Dimitri Cicma. I replied that he was my uncle and my legal guardian. He then embraced me warmly, in the Turkish manner, and told me that my uncle had been one of his best friends and then he assured me that I was now in good hands and that he would see that I was given the best of care.

I told him that I was sorry that it was impossible for me to remain long in Constantinople as it was necessary that I take the earliest possible boat for Bucharest to join my family. He told me that he would be glad to give me a passport and sent me at once to the Romanian Consul to have it visa’d.

I was astonished to find that the Consul was none other than my good friend and benefactor, Consul Braliano, who had helped me enter the Turkish Lyceum. The Romanian Vice-consul was one of my former professors (Cutula) from Janina. I had suffered SO many hardships since they had last seen me that they hardly recognized me. They expressed great sympathy for me and my family, saying that the Romanian people had sustained a great loss in my uncle’s death as Dimitri had been a noble fighter and an excellent leader.

Hearing this, I could only stare stupidly at them as I didn’t know about my uncle’s death. They explained it to me, as gently as possible; Consul Braliano was, of course, completely informed as to what had happened to Uncle Dimitri.

It seems that a month before the declaration of the Balkan War, the Greek Prime Minister Venezelos had arranged a meeting between my uncle and the Crown Prince, Constantine of Greece; the Greeks wished to strengthen their position in Macedonia and proposed complete freedom for the Romanian schools and churches in return for my uncle’s permitting the Greek Army to pass through Turia-Kragna—without any resistance in their way to attack Janina and other Macedonian cities, thus securing a large part of the territory before the Serbians and Bulgarians could make their moves.

Dimitri’s Turkish friends, especially Mustafa Kamal Pasha, urged him to take his family and go to Constantinople to live, he was assured of a post as Turkish Ambassador to Romania as the Turks were trying to improve their relationship with that country. Uncle Dimitri had always considered himself a Macedonian-Romanian first and a Turkish citizen second. His aims were exceedingly simple-religious and cultural freedom for his people, irrespective of political considerations-to leave (our) people and beloved country was out of the question regardless of any personal danger which might be involved.

War was declared and the Greek Army passed through Turia-Kragna without meeting any resistance and continued on to conquer Janina. The Greeks honored my uncle as a “great hero”.

A month later, the Greek Orthodox Bishop at Grebena decided to do away with Dimitri Cicma. They sent a message requesting that he come to Ciprie, a town about half-way between Turia-Kragna and Grebena, to attend an important meeting. Dimitri at once took a few of his soldiers and started out; as soon as he reached the meeting place he was asked to enter the building alone as the matter under discussion was of a secret nature. He was well received and the Captain of the Bishop’s Guards ordered him to send his men back to Turia-Kragna as “everything had been arranged for his safe return”.

He was brought before the Bishop and his cut-throat court, was tried, sentenced to be tortured, and then he was paraded through the city streets; later he was taken about a mile outside the city where they cut off his tongue, plucked out his eyes, and continued various other tortures until he finally died. The body was left unburied. So he was regarded for his cooperation with the Greek Army!

The Romanian Consul reported this tragedy to Bucharest and the Romanian Government intervened, forcing the Greek Government to bury him with highest military honors. ”Sic Transit Gloria Mundi”.

Consul Braliano concluded his narrative and proceeded to advise me as to my own future. “At the conclusion of your visit to your people in Bucharest, I want you to come back to Constantinople; come back full of an increased desire and determination to complete your political education— you alone are equipped to take over for your uncle. I will be in back of you all the way and I know that the Romanian Government will provide more than enough money for you to live comfortably; with your back- ground, you will certainly have a brilliant future-being appointed Ambassador from Turkey to Romania at least, or vice-versa.

I hesitated for a minute and then said, “It is impossible for me to find words to thank you but, for the present, I can’t make any promises. Right now I just want to get to Bucharest and see my family.”

The consul then visa’d my passport and wrote a note to the Captain of the Romanian boat which was to take me to Costanta, from which port in Romania I was to take the train to Bucharest, asking that he take especially good care of me. Consul Braliano also gave me four Napoleons for my incidental expenses and sent me to the wharf in his own special carriage.

We went aboard the boat at about seven o’clock in the evening and arrived at Costanta, the principal port of Romania, at about five in the morning. The distance across the Black sea was not great but it was very rough—particularly on this trip-I was certain that I would never live to see land again. After we disembarked we were all searched again and all luggage was disinfected as we were coming from the war zone.

The train trip to Bucharest took about four and a half hours, I then succeeded in locating the place where my step-aunt, Costa (Uncle Dimitri’s oldest son), Maritsa, and her mother were living. Everyone was happy to see me except Maritsa’s mother—she felt that my Cousin Costa would be a much better match for her daughter; he had inherited Uncle Dimitri’s fortune while I had only the dubious distinction of being able to fill his, now meaningless, position. Of course, I had no knowledge of her change of heart and was sure that she still wished me to marry Maritsa. To assure them that I had now completely renounced all interest in Pusha, I—like a damned fool—gave Maritsa the beautiful handkerchiefs I had received from Pusha; I explained where they came from and said that the donor no longer meant anything to me. I also gave my mother-in-law- to-be the remainder of my money, over three Napoleons, as I had spent very little; needless to say, I never saw another penny of this!

Maritsa’s mother and my cousin were so clever that for almost three weeks I was completely unaware of the situation. One day a cousin of Pusha’s came to the house for a visit and Maritsa’s mother pretenéied great anger and accused me of being unfaithful to her daughter; all in all she augmented the false argument and quarreled bitterly with me. Not long after this, I began to notice the new relationship which had sprung up between my cousin and my fiancée as I became fully aware of their infatuation or whatever it might be called. I was so disgusted that 1 didn’t know what to do; should I break our engagement crudely, should I return to Turia-Kragna, should I go to Constantinople?

No, I would go so far away that I would never have to see any of them again! I consulted many friends and each advised me differently. My Cousin Hristu, who had just finished Medical School at Constantinople, begged me to complete my political studies and take up where his father had been forced to drop the cause of the Romanian-Macedonians. I disregarded all advice. I decided to go to America.

My first reason for this decision was that I remembered a lecture given by one of my professors who had been to America and he described it as a land of promise for anyone who was ambitious, regardless of their social or financial background. The second and more important rea son was that America was so distant that I would never again have to see the people who despised me and whom I had come to abhor. In America, I hoped to create a new future by my own efforts and ambitions, without the help of relatives or friends; a career of my own designing, free of political influence and intrigue.

Everyone disagreed with me; they said that America was not for those of us who were of social title or well educated; also that without a working knowledge of the English language I would be forced to labor in a factory with ”illiterate foreigners”. In spite of these comments, my decision was made, I would remain in Romania no longer. In fact, I was determined to leave before the Easter Holidays.

I realized that if I asked my step-aunt for money to make the trip she would only laugh at my folly, Cousin Hristu could and certainly would have loaned me money, but he would never have permitted my going to America—his only thought was to have me return to Turkey to complete my education. At last I appealed to Vaio Damashoti, an uncle of Maritsa’s and a good friend of mine, asking that he lend me fifty or sixty dollars for a third class fare ticket to New York (he would have been glad to lend me a hundred dollars or more but I accepted only sixty). I received the money on Holy Thursday, had my passport visa’d immediately and a travel agency in Bucharest arranged the complete itinerary for my journey. I was to leave the next day, going to Budapest, Hungary; Vienna, Austria (always my very favorite European city which, from all I had read, exuded the very essence of youth and vitality); Berlin, Germany; Hambourg, Germany; Calais, France; then across the English Chanel and the Atlantic Ocean to New York City and the new, free world of America and a new life.

I should have been elated but I was not, I was so deeply depressed that I would not restrain my tears, I walked the streets of Bucharest, sobbing. No one thought this odd as I had on my Turkish Uniform and they assumed that something had happened to my family or friends in the war!

I finally went home and told them what I had done and that I would leave the following day. They begged me to remain over the Easter Holidays but I refused to alter my plans; the only people who did not regret my leaving were Maritsa’s mother and her new protege, Cousin Costa! Early Good Friday morning I went to say good-bye to my sister; she and her husband tried to make me give up my plan to go to America, but I knew that the sooner I left, the further I went, the better I would feel.

I took the train for Budapest at about six that evening, it was an all-night trip and, because of the Holidays, the train was packed; so with all my luggage I had to stand in the doorway for the entire trip! Saturday, the train for Vienna was still crowded but when we arrived there on Easter Sunday morning there was no one left except the conductor and myself.

We had a long wait in Vienna and, eager to enjoy the famed Viennese cooking, I hunted for a good restaurant. I entered one and addressed them in fluent French as my German was so poor that it would not allow me to carry on an intelligent conversation. The waiter, hearing me speak in French, called the proprietor who, in turn had me thrown out—Vienna and France were on very unfavorable terms at that time!

Hungry and disappointed, to say nothing of confused, I walked back toward the railroad station, looking for another restaurant. I saw a group of people who were spreading their lunch out on the grass close to the station; curiosity and the smell of food drew me to them, I noted that they were speaking Romanian and, although I was very shy, I was also extremely hungry and approached them and asked where they came from. They replied that their home had been in Monistir-Bitolia; I told them of my predicament concerning the restaurant and they graciously gave me an excellent dinner and also some food to take with me; a happy conclusion to one of the saddest Easter Sundays of my life.

Monday we reached Berlin and by Tuesday we had arrived at Hambourg; here they grouped us according to our destination, I was put in with a German couple and a Polish boy. The picnic was over, no more free rides and no monetary independence, only hard work in view from here on.

The agency gave us our tickets, we were assigned an identifying number, for the balance of the trip I never heard my name, only this number—at Ellis Island I was again to hear “Haralambie George Cicma”! We were also told the date of our departure, fourteen days later as I figured it (in Turia-Kragna we used the old calendar which is thirteen days behind the Western calendar which was used in Hambourg), so we were actually scheduled to leave the following day.

I spent the night in the dingy little hotel to which the agency had assigned us. The next morning I arose early and set out to see the sights of Hambourg. I went first to the Post Office and sent cards to my relatives telling them of all the interesting things I was seeing; Budapest, Vienna, Berlin, and also that I was staying two weeks in Hambourg. I wandered around until noon at which time I was over-taken by the young Pole who began to yell, ”Come on, the boat’s going to leave,” this, of course, in Polish which I did not understand. He grabbed my arm and pulled me to the Hotel where he had already packed my bags. He tried to make me understand that I should buy something to eat on the boat; I had only time to get two loaves of pumpernickel bread before they called our numbers and we were herded into trucks and driven to the wharf. A small launch took us to the large Hambourg American Line ship in which we were to make our voyage.

They served us our ”dinner” as soon as we were all on board; a concoction of pork, cabbage and potatoes swimming in grease! I now understood why the Polish boy had insisted that I bring some food with me. I dumped their food overboard and although the bread I had was not much better, it served to dull the keen edge of hunger.

All Third Class passengers were herded like cattle below decks until we were given the number of our “staterooms”, each cabin contained an upper and lower berth, I occupied the lower and a young German had the other—there was barely room for the two of us in the area designated as a stateroom!

We spent most of our time on deck, watching the sea, for the first few days; then it was stormy and they locked us in our cabins. The majority of the people were traveling in groups and had pleasant times; I was all alone and had no one with whom to talk, the young Pole tried to cheer me up, kept trying to talk with me and also, by sign language, urging me to eat some of the terrible messes they served as food. I assuaged my hunger as best I could with the black bread I had purchased and by drinking great quantities of water, once in a while I would drink a little soup but even this was distasteful to me. Everyone on board drank a lot of beer and wine was served at the table—those who saw that I did not drink always came to me and asked me to give them my share!

We all, during the trip, became infested with **pediculi; as we neared our destination this bothered me so much that I threw all the clothes I had been using into the ocean and put on clean ones, even this didn’t help as the German fellow in the upper berth was continually picking them from his body and throwing them down on me. It was, naturally, absolutely impossible to take a bath in the salty water available on the boat. The situation did not improve, although the lice throve, and we approached, eleven days after departure, our destination—Ellis Island—when they told us that we were outside of New York City, I again made a complete change of clothing as I did not want to bring any bugs into the city. I went back to the cabin to sleep and soon began to scratch again as my good upstairs neighbor present me with a new supply; I landed at customs with no fewer pediculi than he!

(To be continued)

**a genus of lice of the family Pediculidae that includes the body louse (P. humanus humanus synonym P. h. corporis) and head louse (P. humanus capitis) infesting humans.

Responses