Vignettes of Greece and America

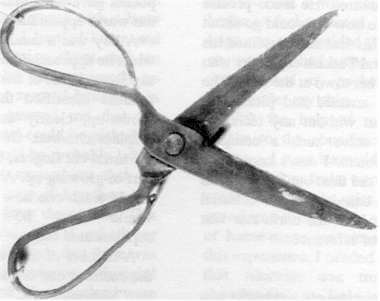

My Grandfather’s Hand-forged Shears

These hand-forged shears were made by my grandfather some 150 years ago, making them the oldest Vlach artifact we have in our home here in Providence, Rhode Island. These shears, an icon, and a few Turkish gold coins were the only things we brought with us when we came to the United States in 1920. The shears were forged by “Master Tego,” as my grandfather was called in the old country. He was considered the town’s genius. Although he died before I was born, I heard about him and his uncanny abilities from my father and from the townspeople of Baieasa.

For one thing, my grandfather had an extraordinary affinity for time. You could always ask him what time it was; even if you awakened him at night, he could tell you the correct time without reference to a clock or watch. He was well known throughout the Zagori region for having built a clock entirely out of wood. Even the Turks depended on him to determine the moment of high noon, at which time they would face Mecca for their mid-day prayer.

Although he had only four years of schooling, he delved into matters that would normally require a knowledge of higher mathematics and physics. One question that fascinated him was the problem that would face two engineers if they were to dig a tunnel through a mountain, each engineer beginning on the opposite side of the mountain and meeting the other exactly in the middle. English and French engineers face the same problem today in calculating how the English and French portions of their tunnel are to meet and join exactly in the middle of the English channel. Although my grandfather never planned to execute such a project, nevertheless he liked the challenge it presented. He made precise calculations as to how he would go about accomplishing this feat and presented his solution to several Turkish engineers who were present in his town at the time. The engineers were amazed and pleased to learn that a man without any technical training could solve such a complex engineering problem. I don’t know how my grandfather did this, but I understand that it was based on a celestial observation in which the north star was the main point of reference.

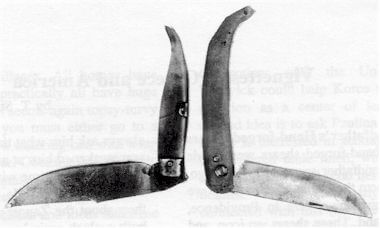

The Custura

The custura (handmade jackknife) was one of the delights of my childhood in Greece. It was made by the local cutler and sometimes by the blacksmith. Every boy wanted such a jackknife. It had a blade shaped like a scimitar and a handle made from the horn of a baby goat. If you were lucky, the knife might even have a small chain attached, so it would not be lost. It was a simple instrument, beautiful and useful. Carrying it in one’s pocket gave the handle a pleasant sheen, the warm appearance of amber.

A boy was a candidate for such a gift when he approached the age of puberty — say around nine or ten. The possession of a knife identified the owner as quite grown-up, clearly out of the class of helpless children. Of course there were the usual cut fingers, but then, that was a part of growing up. A brother or an uncle would teach one how to use it, and later would show how to use more sophisticated tools.

A number of toys could be made with the custura; one of the most popular was the “jumping jack,” a man-figure with articulated arms and legs. He was suspended on two strings strung across two upright handles with a cross-piece near the bottom. When the handles were squeezed, the little man performed a series of acrobatics that amused adults as well as children. Boys also made whistles from green willow branches. And not all objects made were toys; indeed, as we grew up, we were taught how to make fish traps, bird traps and a many other useful articles.

The Apple Tree

We arrived in Westmoreland Depot, New Hampshire, in the fall of 1920 after a frightful voyage on a rusty steamer that took twenty-nine days to cross the Atlantic. Although it only consisted of six houses plus the depot, for us, Westmoreland was America.

About the second day after our arrival in Westmoreland, I noticed a tree loaded with large red apples just across the road from our house. I walked over to the tree and was surprised to see that the ground under the tree was covered with a layer of beautiful apples. I hurried home and asked my sister Marion about such an abundance of apples that apparently no one was picking or seemed interested in them. My sister assured me that the apples on the ground could be picked up by anyone and would be probably left to rot otherwise. She assured me that the farmer would not care if I gathered as many as I wanted from the ground. This I could not believe, and I asked her several times to make sure that there was no mistake. What abundance, I thought! Maybe the streets of Westmoreland were not lined with gold, but a portion of the ground was lined with golden apples.

Apples were scarce in my home town in Greece, and they were considered a great delicacy. If we were lucky, we might have a dozen carefully hidden in the cedar chests, tucked away under the vilendzi, to preserve them for the winter. Cutting an apple in the winter was a ceremonious affair. We could pass the apple around, each taking turns smelling its delicious aroma. It was then cut by our mother, who tried to cut it into even pieces. Each child’s part might consist of about four bites. And now I was under a tree in America and before me were thousands of beautiful apples. Was it true that I could eat as many as I wanted?

I decided that I would gorge myself there and then take home as many as I could carry. But which one would I bite into first? I would pick one, take a bite or two and then see another which was bigger, prettier and more colorful. I must have tried half a dozen apples before I realized that I was being wasteful and began to feel ashamed. Then I spotted a huge one and decided that I would feast on it until I had eaten it all. I did, and then I filled my pockets, even putting some under my shirt.

With the help of my sister — and thanks to the abundance of apples, of course — I soon learned how in America, these delicious fruits were also baked and made into apple pies. Later I was introduced to apple pie with a big scoop of home-made ice cream on top. After this experience, I needed no further proof that America was truly a land of abundance — for little boys as much as anyone else!

Responses