The Vanishing Nomads

In mid-spring, empty hillsides in the Greek-Albanian border region come alive to the sound of sheep and goat’s bells as the Vlachs, Europe’s last semi-nomadic pastoralists, bring their large flocks up from the plains.

The returning Vlachs create a buzz of activity in their remote, isolated villages, which are largely uninhabited in the long winter. Rugs and blankets are unpacked, wood is chopped, ovens are lit, produce and gifts are exchanged and young people are betrothed. At night every house admits the smell of the Vlachs’ favorite dish — pitau — layers of thin pastry soaked in butter and filled with leeks, baked in an iron dish and served with dark red wine.

For centuries these people have spent the summer months wandering with their animals through the vast, forest-clad hillsides of the southern Balkans, following ancient paths known only to them. But nowadays this lifestyle is threatened, and each spring fewer Vlachs make the journey back to their traditional homes.

The Vlachs, who speak an obscure unwritten language derived from Latin and akin to modern Romanian, claim descent from Roman garrisons stationed in the region. Today 90,000 Vlachs live in scattered communities in southeast Albania, the southwest corner of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and on the Pindus mountains in Greece. Many thousands more live permanently in the towns of the central Balkans, virtually assimilated.

Since the 1920s, Vlachs have settled in Germany, Australia and America, where emigre groups have started societies to try to preserve their unique language by telling folk tales and singing Vlach songs. They organize traditional picnics and sports teams to encourage their communities to avoid assimilation and are a forum for Vlachs to discuss their culture and history.

For those who remain in the Balkans, however, maintaining a Vlach identity is increasingly hard. In Albania, postwar agricultural collectivization destroyed patterns of nomadic pastoral life, forcing many Vlachs to find work in the country’s new industrial centers.

But in the remote highlands Vlach culture and language has survived. Shepherds wear the characteristic heavily woven goatskin capes — which are still much prized as trading items.

With no particularly strong religious identity, the Vlachs’ traditional pagan beliefs are covered by a thin veneer of Orthodox Christianity. Many elderly women have a black cross tattooed on their forehead to ward off the evil eye, and their stories of witches and curses are listened to attentively by those with recent troubles. With their parents working long hours, children are brought up by grandparents from whom they learn Vlach customs and the language with its distinctive hissing sounds which have earned them the name Tsintsars, by which they are known throughout the Balkans.

In Shamolle, a mixed Albanian and Vlach village near Korce, the Vlachs provide the inhabitants with milk and cheese with their flocks which graze in the surrounding foothills. And they continue to enjoy many of their traditional pastimes.

“We love eating in the open air. In the summer maybe 30 to 40 people go up into the high ground to have picnics with pitau, wine and musical instruments,” said Aspasia Dhuka, a young school teacher who, like most Vlachs, finds it hard to accept a purely Vlach national consciousness. “I know that I am a Vlach,” said Dhuka, “but I am also an Albanian.” She echoes many educated Vlachs who nowadays speak Albanian with greater fluency than Vlach.

To halt the decline of the language, which has never had an alphabet or any official recognition, a Vlach association was formed in Tirana in 1990. It has 20,000 members; and today many Vlachs hold important posts in wider society — for example, Albania’s ambassador to London, Pavil Gesku, is of Vlach descent.

One of the most evocative places in Albania is the isolated Vlach village of Voskopoje. At first glance it is a typically dilapidated Albanian hamlet, but glimpses of white stone tell of the prosperity it enjoyed in the 18th century as a commercial and intellectual center with decorated Orthodox churches. Its population engaged in all manner of trade and commerce. Despite its success, Voskopoje suffered from raids by bandits. After years of devastation and pillage Voskopoje disappeared, leaving only a handful of shepherds’ huts among the sacred buildings. Two centuries later the descendants of those Vlach shepherds live among the ruins of the shining marble streets and huge churches.

Set among rolling hills and rich pasture-land, Voskopoje is now the center of Albania’s pastoral agriculture. In the town’s dingy taverna, Vlach men huddle in clouds of smoke talking of sheep and goats and planning their winter trips to work in Greece. Most of Voskopoje’s men-folk have worked in Greece, many have relatives there, others have brought back wives.

“This was once a major town where Greeks and Vlachs lived together and today we still help each other,” said Zguri, one of Voskopoje’s oldest residents, as he showed me around some of the magnificent churches slowly being restored by Greek-funded craftsmen.

Across the border in Greece, many Vlachs in the Pindus are barely conscious of being Vlach, thinking of themselves instead as Greeks speaking a strange language. But there are Vlach communities with a strong identity, scraping an existence on the edge of Greek society. At a wedding in Pili, a purely Vlach village in Greece’s Prespa region, a group of men were angrily discussing how to protect their livestock from being stolen by hungry non-Vlach Albanian illegal migrants, who wander through the forest to avoid detection by Greek border police.

“We have lost over 20 sheep this winter,” said a burly young man standing next to me. He then matter-of-factly described how he had killed an Albanian refugee while out hunting last year. He had stumbled across the unfortunate Albanian asleep in a clearing. After slitting his throat with his hunting knife, he left the body as a reminder to other Albanians not to kill Vlach sheep.

There are several historically Vlach villages in southwest FYROM but today these have a fraction of their pre-war population with many families having emigrated in the 1950s to Australia along with thousands of other Yugoslavs. In the 1970s greater mobility caused more breakups of extended Vlach families as young people moved to the cities of Prilep, Bitola and Skopje, where today, high in the tower blocks you hear mothers shouting to their children in Vlach.

As young Vlachs settle in the larger towns and cities of the Balkans, they hear confusing stories about their origins. Greeks claim Vlachs are descended from Greek women who married Roman soldiers. Many Albanians believe Vlachs to be descended from Thracians who lived alongside them during Illyrian times. Romanians think Vlachs are of pure Romanian stock, having somehow been cut off from the main body of their kinsmen south of the Danube.

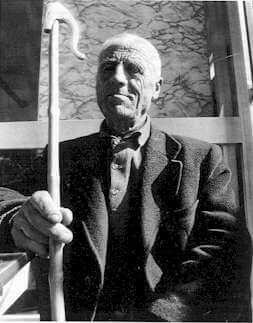

Samarina, 1989: Old Man

(Photo ©1995, James Prineas)

The development of a purely Vlach national consciousness has been hindered by the fact that Vlachs have never been able to read or write anything in their language, always being taught to use the alphabet–Greek, Roman or Cyrillic–of the country in which they lived.

“By teaching our children to read and write their own language, we will encourage a sense of unity among the different Vlach communities to work together to preserve our culture,” said Tassos Kupatshari, a Vlach from Detroit, visiting relatives in Pili.

To thrive, it seems, the Vlach language must have an alphabet. But there is controversy over the choice of which alphabet to use. So the Vlachs are divided not only by frontiers but also by internal dissent and the curious vagueness many Vlachs profess about their own heritage. Unless agreement is reached on a standard alphabet, the future of the language, and of the culture, is bleak.

Despite the efforts of Vlach associations to preserve their language and customs, there is much uncertainty surrounding the future of the Vlachs. Modern school life is eroding their speech and migration to the towns in search of permanent jobs means many will not return for the annual spring trek back to traditional highland pastures. •

(Editor’s note: This article was reprinted with permission of the author, who sends her “best wishes to your Newsletter and to the Vlach community in America.” It originally appeared in the 4-10 April 1996 issue of The European Magazine. Ms. Vickers is the author of several books, including The Albanians: A Modern History.)

Responses