Southern Albania, Northern Epirus: Survey of a Disputed Ethnological Boundary

This paper is based on several short visits to Albania between 1992 and 1995. It is, I hope, an objective and accurate account, but makes no pretense at giving a full or final picture. A full picture could only be presented if every village in the area were visited, no light undertaking in view of the remoteness of some communities. A final picture is impossible to imagine at a time when massive emigration to Greece has radically altered the numbers in many villages, and will alter the speech of their inhabitants.

My researches were conducted mainly in the extreme South-East of Albania, comprising the administrative districts of Sarandė, Delvinė and Gjirokastėr together with a small portion of the district of Vlore. I make some preliminary observations about, and hope in time to extend my investigations into, areas northwards and eastwards to include the whole of the Vlore districts, and the districts of Fier, Ballsh, Berat, Tepelenė, Permet, Ersekė and Korēė.

I am concerned mainly with three different groups: Albanian speakers, Vlach speakers, and Greek speakers. There are also Albanian-speaking gypsies, and some of the Albanians are Muslims (many of these are the so-called Tsams, expelled from Greece at the end of the Second World War — they present a particularly thorny problem in view of the reallocation of land). Almost everyone now speaks Albanian, although I did meet one old couple who only spoke Vlach, and another old lady whose Albanian was a great deal worse than my Greek. Some Albanians and some Vlachs speak a certain amount of Greek, and more will do so as a result of seasonal emigration. I even found one village (Nokovė) where the Albanian minority had learnt Vlach, the language of the majority. But the regular use of a language in the home is my criterion for determining which villages belong to which ethnic group; it is a rough and ready criterion, but one recognized by most of the inhabitants of the area who talk about Greek villages and Tsam villages and mixed villages (most villages with Vlachs in them are mixed) as if there could be no dispute.

The borders of Albania were not fixed until just before the First World War and there were minor alterations to them after the war. In both world wars Greece occupied briefly a large tract of land including almost all the area under discussion. Map makers of various nationalities produced ethnological maps with very different conclusions, exaggerating the extent to which Albanian or Greek or even Bulgarian and Vlach was spoken. More objective maps are supplied by the great historian of the Vlachs, Gustav Weigand, and the great historian of ancient Greece, Nicholas Hammond, but even these have their faults.

Weigand writing over a hundred years ago is of course now out of date, although perhaps his map does reflect the conditions of his time. Oddly for a student of the Vlachs he does not seem to mark many Vlachs in the area we are investigating. My researches showed that many present Vlach settlements in Albania are recent, and this might support Weigand. But the Vlachs in these settlements must have lived somewhere, and from what I could gather many of them were permanently on the move before Enver Hoxha found homes for them. In addition, Weigand places the Greek-Albanian linguistic border too far south. He does acknowledge some Greek speech in the Himarė district, and some Albanian speech near Igoumenitsa, indeed suggesting that the whole coastline is an area of mixed speech, as it was before Greece expelled the Tsams. But inland by drawing the linguistic frontier well to the south of the present political frontier Weigand is undoubtedly doing an injustice to the Greek- speaking population of southern Albania.

Hammond’s book was published in 1966, but reflects conditions between the wars, when he conducted extensive archaeological work in the area. His ethnographic map is thus out of date in marking Albanian villages south of the border. The Greeks expelled the Tsams and assimilated the Albanian orthodox speakers. North of the border Hammond’s observations still hold good today. They still speak Greek in Poliēan and Himarė. Indeed, Hammond surprisingly appears to underestimate the number of Greek villages. Thus, he does not mark Finiq as Greek or mark the many Greek-speaking villages south of Finiq or south of Gjirokastėr. Piqeras, Lukovė and Shen Vasil are noted as Greek in his map, but in his text he seems to regard Qeparo as the most southerly Greek village of the Himarė area. In 1993, looking for Vlachs alleged to be in the Lukovė and Shen Vasil, I found Greeks, but no Greeks in Qeparo. Hammond does not mark Vlachs in Albania at all.

Weigand’s map marks a clear linguistic frontier, but has the disadvantage of all such maps in that it paints as Greek or Vlach or Albanian large areas of uninhabited mountain or swamp. Hammond’s map avoids this, but we do not get any idea of a linguistic frontier, nor does he give an account of mixed villages. In Shattered Eagles (London, 1995) I drew a map of Albanian Vlach villages, using information supplied by Albanian Vlachs, but this information failed to take account of the fact that sometimes only a small portion of the population spoke Vlach, while in other villages a substantial number or even the majority were Vlach-speakers. Thus in Ksamil, I only found one Vlach family (recently moved from Voskopojė), and in Lekel I only found the village schoolmaster who had a Vlach father, knew a great deal about Vlach history, but spoke less Vlach than I did. On the other hand, I unaccountably missed the important Vlach village of Stjar.

My present map (Editor’s note: this map was not available at press time) marks what I take to be the linguistic frontier between Greek and Albanian with representative Greek, Albanian and Vlach villages noted. In charting the Vlach villages I have tried to confine myself to those where the Vlachs form a prominent part of the population. In the very southern part of the country, as I noted in Shattered Eagles,there are Vlachs in Ksamil, Vrion, Xarrė, Mursi and Shkallė. Only in the village of Shkallė do they form a majority (seventy percent Vlachs and thirty percent Tsams). In Xarrė the proportions are reversed, but there are also some Greek speakers, and not all the Albanian speakers own up to being Tsams. Xarrė has a brand new mosque; Mursi, an Albanian orthodox village, two handsome churches. Further north walking on Easter Sunday from Stjar (Vlach) where I had red eggs given to me, to Finiq (Greek) where there was a church service and a dance proceeding simultaneously, I stopped at a cafe and drank some beers with some Tsams.

All this is very confusing. But some conclusions emerge from my findings:

1) Any attempt to redraw the frontier more in line with the ethnic composition of the country would produce a very peculiar boundary. The villages near Himarė are isolated from those further south. The villages in the south of the country between Sarandė and the Greek border are cordoned off from this border by a line of villages, Vrine, Xarrė, Shkallė and the town of Konispol, inhabited by Vlachs or Tsams (although Mursi is apparently Albanian Orthodox). There is a large pocket of Greek villages north of Vagalat stretching as far as Finiq, but to the east of these is the village of Pandejlemon, entirely Tsam, and to the west Sopik, which is Albanian. This pocket almost, but not quite, reaches the Greek villages of the Drino valley, as Muzine on the pass is Albanian-speaking, although the church is being restored with aid from Cyprus. The villages on both sides of the Drino are Greek as far as Delvican, just south of Gjirokastėr, but between these villages and the area around Poliēan there are Albanians at Libohovo and Vlachs further north. This is the present position; it is very difficult indeed to find out what the position was a hundred or even fifty years ago. It is clear that in and just after the war a good deal of what is now called ethnic cleansing took place.

2) It seems from my examination that the number of Greek speakers has been greatly exaggerated. Commentators give a variety of figures ranging from 40,000 to 400,000 and say that certainty is difficult to achieve in view of conflicting claims and conflicting criteria. Albanian census figures on Greek speakers showed 40,000 in 1961 and 58,000 in 1981, a rise in proportion to a general increase in the population. The figure of 400,000 can only be reached if we count as Greeks not only Vlachs, but all Orthodox Albanians, whether they speak Greek, Albanian, Slav or Vlach. This was the figure given in The Independent of 17 August, 1993. British commentators tend to look at figures halfway between the maximum and minimum figure. This applies to both Greeks and Vlachs, and there are some equally wild claims by emigre Vlach organizations, but the official figures are as low as 10,000. Of course there are other ways of increasing the number of Greeks and Vlachs. Quite a few Albanians know some Greek. Quite a few claim Greek or Vlach origin. Given the urge to escape Albania at all costs it would be tempting to claim Greek or Romanian consciousness. But the criterion of speaking the language regularly at home is probably the most objective.

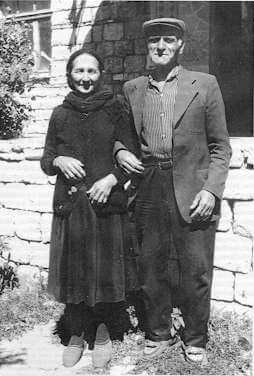

Elderly Vlach couple in Albania

(Photo: Lala Meredith-Vula)

My own estimate using this criterion would be that there are about 40,000 Greeks in the area under discussion and about 15,000 Vlachs. I would also guess with rather less first-hand evidence that in the rest of the country there are about 20,000 Greeks and 35,000 Vlachs. I base my calculations on the following considerations:

· The useful, if eccentrically written map, entitled Republic of Albania, Organizative Administration, published in 1993 has some interesting statistics. It gives the total population of the Sarandė, Delvinė and Gjirokastėr districts as 158,110. To this we must add the area around Himarė, with about 9,000 inhabitants. The map also gives the population of various sub-districts and the number of villages in each sub-district, although it is less informative about what villages are in each sub-district. The population of Gjirokastėr is given at 24,200, Sarandė as 25,400, Delvinė and five surrounding villages as 10,800. From this population I have assumed 15,000 to be Greek. From the sub-districts of Livadha (fifteen villages, population 8,600), Dhiver (eleven villages, population 5,400), Vrisera (eighteen villages, population 17,900), Sofratike (sixteen villages, population 5,100), Poliēan (six villages, population 2,300), Finiq (seventeen villages, population 10,000) and Mesopotan (fifteen villages, population 5,100), I have assumed 20,000 to be Greek. With the exception of Vrisera, of which I know nothing, all the names I have mentioned I know to be Greek-speaking villages in every sub-district. Seven villages in the Himarė district are supposed to be Greek, and I have assumed a population of 5,000 here. More exact census figures could prove me wrong.

· My figures for Vlachs are based on visits to a number of villages near Sarandė and Gjirokastėr. Novoke and Andon Poci were totally Vlach, Shkallė 70% Vlach, Labova ė Madhė 50% Vlach, a number of other villages north-east of Gjirokastėr 25% Vlach. All these are in sub-districts outside the Greek sub-districts I have mentioned previously. Inside the sub-districts, reducing the number of Greeks are Vlach communities at Stjar, Bakaj, Metoq and Poliēan. Interestingly, the sub-districts of Labova ė Madhė, which I began to explore, and Nivan in the Zagorie, which I looked at wistfully from Poliēan in a hail storm, have fourteen villages and a total population of 29,000. If half of these villages had Vlach inhabitants and were like Labova ė Madhė divided equally between Vlachs and non-Vlachs this would give a Vlach population of 7,250 for these two northern sub-districts alone. I think I have met enough Vlachs in Stjar, Shkallė, Novoke, etc. to boost this figure to 10,000 without fear of contradiction and am assuming that the remaining five thousand could be found in the rest of the three districts, including the three main towns.

· The districts of Permet and Ersekė are sparsely populated (70,000 inhabitants) and though they border on Greece do not, I think, have many Greek speakers. There are plenty of Vlachs, notably at Borove and around Frashėr, a town which gave its name to Farsherotsi, a general name for Albanian Vlachs. The small district of Billisht (30,000) inhabitants contains few Vlachs and probably more Greeks. The district of Korēė, which only just borders on Greece near Lake Prespa, is a large one with 192,000 inhabitants. For some reason Albanians are insistent that there are few if any Greeks here, perhaps because Korēė (or Koritsa as the Greeks like to call it) always formed part of the Greek claim, and there was a border rectification in favor of Albania after the First World War. There are in this area important and old Vlach settlements like Voskopojė and Vithuq and interesting Slav villages.

I visited Borovė in 1993. The founders of the main Vlach society in America, the Society Farsarotul, came from southern Albania.

In 1913 Greece was awarded the largely Slav-speaking area to the west of Lake Prespa. This was restored to Albania reluctantly in 1926, there being minor border rectifications simultaneously near Lake Ohrid with Yugoslavia. In the Second World War as in the First, Greece occupied Korēė briefly, and Albania subsequently gained territory to the east of Lake Ohrid (albeit for a short period).

More work needs to be done here and also of course in towns like Tirana, although Greek and Vlach speech tends to die out in towns, and many of the so-called Greeks in Tirana and Elbasan are in fact Vlachs.

3) There has been of course some inter-ethnic tension. In April 1994, two Albanian soldiers were shot in the Greek village of Peshkepi. In September, five Greek Albanians were sentenced to imprisonment in connection with this crime, but in February 1995 their sentences were commuted and a new apparently more friendly period of relations between Greece and Albania was inaugurated. I had been warned of danger because of inter-ethnic tension and the problems of illegal immigration to Greece, but was everywhere treated with great courtesy and hospitality, even though I made it clear that I was interested in ethnic minorities. Unlike Yugoslavia, Albania has a tradition of inter-religious tolerance, and this was probably fostered by Enver Hoxha’s ban on all religions. Hoxha was fairly kind to the Greeks, allowing them to have educational rights. By settling in strategic villages Vlachs who were in some sense Greeks and yet not Greeks, and by settling Tsams, who were in some sense Albanians and not Albanians, Hoxha did something to create racial harmony. The Tsams had been evicted from their homes and the Vlachs had no settled homes; by giving them homes Hoxha did much to ensure their loyalty.

4) Of course all is not entirely sweetness and light, although I was frequently assured that it was. The emigration to Greece has meant that the land is sadly neglected, the fields untilled, the terraces ignored, the fruit trees cut down for firewood, the irrigation channels turned into marshy swamps. The Greeks probably have the best chance of getting visas for Greece, followed by the Vlachs, and this has brought prosperity to some homes, although it has also shattered families and brought about a certain amount of envy from people like the Tsams who are less welcome in Greece. In the matter of redistribution of land there is a question mark over the claims of Tsams and Vlachs, both of whom arrived late in the day.

5) It is the contention of Professor Hammond that the Greeks were the original inhabitants of this area and the Albanians and Vlachs latecomers. This is the official Greek line, coinciding with the view that ?Macedonia was and is and always will be Greek.? Albanian historians are keen to stress that even southern Albania was largely inhabited by Illyrians until conquered by Rome, and they claim Pyrrhus of Epirus as one of their heroes. I was asked by a kindly policeman at Sarandė whether I thought Pyrrhus was Greek or Albanian, and gave a diplomatic answer, wondering if many Albanians at Heathrow were being quizzed about the ancient Britons. I cannot see that it particularly matters whether the Greeks or the Albanians got to southern Albania first. Clearly there were often movements of population. The Byzantine empire lost control in the seventh century, regained it in the tenth, lost it again in the fourteenth century when Albanians and Vlachs penetrated far into Greece. Churches provide some evidence here. Information from Ottoman sources and English travellers suggest that at the beginning of the nineteenth century the valley of the Drino was still largely Albanian. The pocket near Himarė and Poliēan may have always been Greek.

The position of the Vlachs is more obscure. In most villages I was assured that the Vlachs had been wandering the land until the end of the war when Hoxha had settled them first in straw huts and then in 1967 had built houses for them. What I could not find out is how long they had been wandering. Hammond talks of Vlach shepherds in the area before the war, and there are photographic records of these Vlachs. In one or two settlements there were old churches, and in one or two, notably Labove ė Madhė and Hlomo there were the kind of large houses built by rich merchants that I have seen in such Vlach settlements as Kruševo (Yugoslavia) and Neveska (Greece), although when I asked about these merchants I was told that they were either Albanians or Greeks. Even if they were Vlach that still does not take the Vlachs back beyond the eighteenth century.

The fact is, the history of the Vlachs for the two thousand years after the Roman invasion of the Balkans still remains largely a mystery. But it is a mystery I hope to unravel by further visits to Albania.

1 I visited the area near Korēė briefly in 1992 at the time of the General Election and again in 1993. This area with its interesting mixture of Greeks, Vlachs and Slavs as well as Albanians is one that would repay detailed investigation. There is an account of the Slav minority near Lake Prespa in New Albania (1990, p. 31) by Halil Lala, giving an optimistic account of the area, stressing the teaching of Macedonian in the schools.

2 H. Wilkinson, Maps and Politics (Liverpool, 1951) is a mine of information about the eccentric cartography of this region, although his main area of interest is Macedonia rather than Albania. On p. 239 he has a map produced by the Albanian colony in Turkey showing tiny dots of Greeks in Southern Albania but a solid bloc of Albanians extending as far south as Preveza in Greece. No Vlachs are marked in Albania, and his version of the Albanian Slav border is well to the East of Lake Ohrid with considerable blocs of Albanians east of Lake Prespa. This map was produced in 1920; in 1919 the Romanian A. Atanasiu (p.244) published a map with roughly similar boundaries between Albanians, Greeks and Slavs, but great swathes of Southern Albania apparently inhabited by Vlachs. The Greek War Office produced in 1919 (p.194) a detailed map of Southern Albania showing considerable sections of the country as far north a Himarė, Tepelenė and Voskopojė with a mixed Greek and Albanian population, but with the Greeks definitely in the majority. A Bulgarian map of 1917 produced by J. Ivanov (p 199) shows the Bulgarian-Albanian border well to the West and South of Lake Prespa.

3 G. Weigand Die Aromunen (Leipzig, 1888). Weigand never visited southeastern Albania, though he visited Vlachs near Fier and Vlachs and Slavs near Korēė. His drawing of the linguistic frontier near Lakes Prespa and Ohrid is a good deal more accurate than most partisan maps produced at the time of the First World War.

4 N. Hammond Epirus (Oxford, 1966). Hammond was of course only incidentally interested in modern ethnology as opposed to ancient history, where his researches, carried out in difficult circumstances, are invaluable.

5 I tried unsuccessfully in 1994 to find Albanian speakers in Filiates, Paramithia and Margariti. The coastal villages near Igoumenitsa have been turned into tourist resorts. There may be Albanian speakers in villages inland, but as in the case with the Albanian speakers in Attica and Boeotia the language is dying fast. It receives no kind of encouragement. Albanian speakers in Greece would of course be almost entirely Orthodox. The Tsams expelled to Albania present a real problem to both governments. There is a moving if not accurate account of this minority in Albanian Life (1955) by Fatos Meo Rrapaj, pp. 15-16.

6 J. Pettifer and H. Poulton are the main British authorities on Balkan minorities. One must pay tribute to their diligence and their objectivity, if not their consistency. Poulton in The Balkans: States and Minorities in Conflict (London 1993) gives the figure of 40,000 to 400,000 for Greeks, but wisely does not try to resolve the difference. Pettifer in The Greeks: The Land and the People since the War (London, 1993) boldly gives the figure of 200,000. In his Blue Guide: Albania (London, 1994) he more cautiously describes the figure of 200,000 as an irredentist claim. In The Minority Group Report on the Southern Balkans (London, 1994) edited by Poulton and Pettifer the number of 250,000 is given as a maximum claim, while the minimum claim by the Albanian government is said to be 35,000 to 40,000. Working in rather a different direction, but still in English, the admirable Greek Monitor of Human Rights, September 1994 p.21 gives various figures for those who voted for the party standing for Minority Rights in general and local elections. These figures (40,000 and 56,000) of course take no account of under-age voters, but as the compilers of the report admit they do take account of voters for minority rights other than Greek minority rights.

7 I am grateful to the Soros foundation and the University of Warwick for enabling me to visit these villages and for the help of Miss L. Meredith-Vula and for the hospitality of the Kotoni family in Gjirokastėr.

8 I visited Borovė in 1993. The founders of the main Vlach society in America, the Society Farsarotul, came from southern Albania.

9 In 1913 Greece was awarded the largely Slav-speaking area to the west of Lake Prespa. This was restored to Albania reluctantly in 1926, there being minor border rectifications simultaneously near Lake Ohrid with Yugoslavia. In the Second World War as in the First, Greece occupied Korēė briefly, and Albania subsequently gained territory to the east of Lake Ohrid (albeit for a short period).

10 Many Albanian intellectuals, including the present ambassador to the United Kingdom, come from Tirana but are of Vlach origin. In comparison with other countries, there has perhaps been less movement in Albania from the villages into the towns, and less assimilation of minorities in these towns. I frequently encountered the phenomenon of both parents working, and the children learning a minority language at their grandmother’s knee. It is therefore possible that I have underestimated the number of Vlachs and Greeks in urban centres, although such families do become assimilated fairly rapidly (as in the case of H.E. Pavli Qesku).

11 But the churches are not properly recorded either by Albanian writers, who were principally interested in the Illyrians and not very interested in churches, or by foreign writers, who were deprived of access to all but the best known churches (which do indeed tend to show either a sixth- or a tenth- or a fourteenth-century Byzantine presence. See the article by S. Hill AByzantium and the Emergence of Albania@ in T. Winnifrith Perspectives on Albania (London, 1993). At Labova ė Supėrme I guessed (correctly) that the church was of tenth century origin, yet I was told confidently by the kindly village schoolmaster that the church had been built by the Emperor Justinian in the fifteenth century.

12 See Shattered Eagles p.102. Dr. F. Duka of Tirana University informs me that Ottoman records suggest that in most of the early modern period there are plenty of Vlachs, but few Greeks, in the Drino area.

13 Hammond, Epirus, pp 23-7, 94, 214. Photographs of Albanian Vlachs before the war are in the possession of Mrs. Dodgson of Alcester (and were in the possession of the late Harry Hodgkinson).

Responses