Haralambie George Cicma Autobiographie Part III

PART III (Continued from last issue)

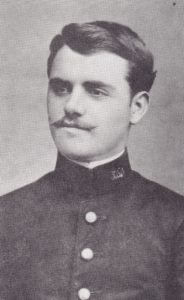

Student George Cicma in Turkish Lyceum’s uniform

On the tenth of September, 1908, five girls and I started for Monistir- Bitolia; the girls were to attend the Romanian Normal School there; we traveled by horse in a caravan. We rode all day, spent the night at Grebena, the following day we slept in the forest as we were far from any town; early the next morning we set out for Sorovitch where we were to take a train, this was scheduled to leave daily, at four o’clock in the afternoon and was the only train available for Monistir-Bitolia. We made the connection successfully and the ensuing three hour ride was un- eventful. The girls went to their school and I went to the dormitory and had the evening meal with the other students, they had also provided lodging for the night for me.

The following day I had an inter-view with Professor Zuca who had promised Uncle Dimitri that 1 would be accepted at the Lyceum. He would give me no definite answer to my questions and said only that he had arranged to have me see Inspector General Tacit. Accordingly, I called at the inspector’s office. He received me kindly and tried to make me under- stand that, although Professor Zuca had assured us of my acceptance, he-the Inspector General of all Romanian School was very much opposed to the idea. He believed I would be unable to follow the classes without first fulfilling the necessary prerequisites which might take two or three years. He, personally, was willing to pay my expenses for the trip to Salonica in order that I might continue my commercial studies there! Naturally, I told him I would be unable to make any decision until my Uncle Dimitri had been fully in- formed of the situation. The great Inspector General (when 1 think of you now, he reminds me greatly of Poo-Bah in Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado”) assured me that he would assume full responsibility for making my uncle understand the situation. I was bitterly disappointed and completely unable to decide upon a future course of action. Later that same day I met an old friend, Mircia Braliano, son of the Romanian Consul- General at Monistir-Bitolia, who had been a classmate of mine at Janina. We were delighted to see each other and I was happy to have someone to tell my troubles to-we talked away the remaining hours of the afternoon and then I went home with Mircia to meet his father. I explained what had happened and Mr. Braliano urged me to forget the Romanian school and enter the Turkish Lyceum. He felt that this would be my uncle’s wish, too and assured me that with Dimitri’s power behind me, I would have a much better opportunity to make a place for myself in the Turkish rather than the Romanian Lyceum.

I was terrified at the thought of attending the Turkish School, I was positive that I would not succeed as I had so very little knowledge of the Turkish language. Mr. Braliano disregarded my protestations and sent a messenger to the head of the Lyceum, arranged for my acceptance and paid my entrance fee; naturally when my uncle understood the situation he repaid the money. Inspector General Tacit was furious to learn of Consul Braliano’s intercession in this matter—they were never on good terms even at the best of times. Mr. Tacit tried several times to bring me to his office in an attempt to change my plans; however, my decision had been made for me and I refused to be diverted from my resolution.

The Turkish Lyceum owned and occupied some of the largest buildings in Monistir-Bitolia. The main structure was four stories, an incredible height at that time, and was built entirely of marble. On the first floor were class-rooms, the second housed the administrative offices, the third and fourth were used as dormitories. There was a special dining-room, kitchen and storage area in a separate building. A well-equipped hospital occupied another section, all buildings were constructed around a yard— the largest enclosed courtyard of any school in the area. On one side was the Jami (Mosque) where pupils and teachers went five times a day for prayer; in the center of the court was an immense lavatory with about two hundred faucets; here everyone washed; five times a day the students removed their shoes and stockings, rolled up their sleeves and pantslegs, washed feet, legs, hands, arms, and faces before entering the Jami for prayer. The classrooms were built on either side of a long corridor which had glass windows running the entire length of it so that the Hajah (Principal) could see what was going on in the classes, as he walked up and down the hall. In the basement of the building there were special smoking rooms where all the students who desired this dissipation were free to go after and between classes; if anyone was caught smoking anywhere else, be it in their room, the corridor or the yard, they were severely punished.

Approximately two thousand students were registered at the school, of these only four were Romanian, three were Greek, two Serbian, Bulgarians numbered twenty-five, the remainder were all Turks. Immediately after my enrollment, they gave me a test to determine just how much Turkish I knew, fortunately I read so well that they put me in the second form (year) rather than the first. Actually they wished to put me into the third form but a Romanian boy, Constantine Cazano, persuaded me to remain in the second, promising me that he would help me with the work and the language. I believed him and so lost a year as after the first week— when he discovered that I expected him to help me rather then give him the help he anticipated – he left me to my own resources.

The curriculum at this school differed greatly from the Romanian institutions. They had only the Turkish and French languages, Mathematics, Geography, and History comprised the principle subjects; the entire course required eight years’ study. You went to school the whole term without any examination until June. You were then given an oral exam in all studies, no student was exempt unless he was deathly ill.

The school was supported by the Turkish Government, they supplied our uniforms, all clothing, meals, rooms, and tuition. Each student was listed by number as well as by name, this was displayed prominently on your collar (mine was 102); if anyone misbehaved outside or inside the school, their number was noted and reported to the Hajah. Incorporated in the school was a nasiy dungeon; on their first offence, students were given twenty-five lashes on their feet and were thrown into the dungeon for two days with only bread and water. The second to fourth offences received double the punishment and after the fourth, the student was expelled.

We had only one day off each week, Friday (their Sunday, but the few Christians who were enrolled were sent to their own church on Sunday. At first, some of the boys took advantage of this privilege and did not attend services. This was, of course, discovered and they were sent under guard thereafter.) Friday afternoon at five we had to present ourselves for the evening meal; at the door a man was always stationed, his duty was to smell our breath for drink and search us for pocket knives or firearms – any offenders were reported immediately and dealt with harshly. Needless to say there were few repeat offenders!

On the first day of school, I went in and sat at the desk assigned to me, it had a hinged cover. I removed my fez and put it in the desk; I didn’t know what to do then, so I took out my music book and began to sing, “Do, re, mi,” loudly. I noticed that all the boys looked at me in surprise but I considered that this was because I had such an unusual voice!

The Hajah was patrolling the corridor, looked in, saw me sitting at my desk with my fez off, opening my mouth wide and beating time with my hands and feet. He entered, heard what I was doing and rushed me into his office as quickly as he could; be began to speak so rapidly in Turkish that I could not understand him and had to send for one of my countrymen to interpret for me. I was told that music was forbidden in the Turkish schools except for the few who were allowed to sing the Koran; and I must never take off my fez- truly I do believe that a great many students slept in theirs. I was pardoned for these two grave errors because of my ignorance or their customs, but you may rest assured that I learned my lesson well.

It was fortunate that we were not called upon to recite in class; I could not speak Turkish well and even problems written in that language were difficult for me to understand. There was no Romanian-Turkish dictionary, at that time, available , thus I had to study the language from a French-Turkish dictionary and grammar. Later, I attempted to write my own Romanian-Turkish lexicon but never completed it. At first I had to express my desires by sign language or by definitely showing then what I wanted, i.e. bread, meat, salt, pepper, etc. The students were very considerate , so were the teachers, and always told me, politely, of any mistakes I made nd informed me as to the name of the article I wished. Soon I could carry on a rudimentary conversation, could understand when spoken to and could read my assignments freely; at the end of the year I was quite proficient – to my surprise and to the surprise of the professors.

June fifteenth was the official end of the school year; on the first day of May each year the school had a great celebration, large bands of musicians furnished music and many other forms of amusement were available, hundreds of lambs were were roasted, on this day all classes were suspended. For the rest of the month we had to stay inside the yard and study; we erected tents and groups of congenial students would congregate to study in their shade. Only if we had an excel- lent and very important reason were we allowed to leave the grounds, all requests were thoroughly checked before permission was granted.

All examinations were oral; the principal and the teachers had a conference, each teacher chose three of the city’s most learned citizens to the examining. Pupils were examined privately in a room which contained only five chairs and a desk. The three civilian examiners sat at the desk, asked questions and marked the student; all the teacher did was to admit and dismiss the nameless pupils, This system was utilized so that each student would be judged fairly- bribery was common among the Turks and even the teachers could not be trusted to mark impartially.

After the examinations were completed, the Hajah would appear in the second story window of the main building and, from this vantage point, would read the final results of the examinations; it had been proved that it was useless to post a list as it would be torn to shreds in a short time. The students often staged riots after the marks were read and had to be held in check by the ‘porters’ as the watchmen were called. I did very well in examinations, in spite of my difficulties with the Turkish language, and passed all my subjects.

I returned to Turia-Kragna alone, the Romanian Normal School had closed two weeks earlier than the Turkish Lyceum ad the girls had already left. The Turkish Government provided an escort of soldiers to protect me from outlaws on the journey; my uncle’s prominence made me an important student and they extended every possible courtesy to me.

I was not allowed to do any manual labor that summer, this being below the dignity of the position I now occupied as one in training for the rank of Khayme-Khan (Governor of a small province). My uncle had now decided that I was to become his successor in affairs of state!

It was necessary that I wear wear my school uniform at all times; the Turkish who were stationed in Turia-Kragna were at my command and we went often on hunting expeditions in the mountains or had picnics on the beautiful plateaus nearby. Occasionally, I would have the soldiers clean out a spring or make fireplaces, etc. and before the summer was concluded we had improved many of the picnic areas.

The fall of 1909 again found my first cousin, Ephtimia Vaeni, four other girls and myself traveling in a caravan to Monistir-Bitolia as we had the previous year; Mary Mihadash, loana Dalabec and my cousin were to be second year students, Maritsa Damashoti and Pusha Cutupolio were to enter the Normal School for the first time. Pusha was an attractive, well-built and exceptionally intelligent peasant girl, she was a good friend of my cousin. I found her very attractive but as yet I had not the slightest knowledge of what love meant and could not understand the feelings she aroused in me.

Several times throughout the school year, Whenever I went shopping with my cousin, she always insisted that we take Pusha along; I had no objec- tions to this as I had no idea of their motives! It seems that the girls were always talking among themselves and that Pusha had openly declared her great admiration of me; my cousin decided that she would advance Pusha’s cause, so one day she spoke to me about her.

I was considerably embarrassed and changed the subject at once, I was not sure of my own sentiments and did not wish to commit myself.

This second year at the Lyceum was much the same as the first and, after successfully completing my examinations, I was again escorted home with a Turkish guard.

We returned to Monistir-Bitolia in the fall, the five girls and I. We remained over night at Grebena but the next morning we were unable to find a Christian caravan bound for Sarovitch and were forced to hire into a Turkish caravan. We each had two horses, one to ride and the other for our luggage, all during the trip Pusha tried to remain as near me as possible.

Shortly before dusk we neared a small Turkish town where the owner of the caravan lived; my cousin and I took, inadvertently, a wrong turn and were separated from the others.

The Turk soon found us and guided us back, the other travelers were impatient at this delay, it was now too late to continue on to Sarovitch, so we were forced to remain in the village. The Turk took us to his home, this consisted of two mud huts, one for his family and one for guests.

lt is a Turkish custom to welcome visitors by preparing everything fresh, even bread; when the food was ready they brought it to our hut—a veritable Turkish feast. The girls had religious superstitions and would eat none of it, would not even drink water. I begged them to eat, as the Turks are very easily offended; his wives (four) kept peeking in the door to see the girls, who continued in their refusal to either eat or drink. The Turk was disappointed but I assured him that the girls were neither hungry nor thirsty so he retired, satisfied, to his hut.

I urged them to at least drink water, but they would not. I then threatened them, “After I have had all I want, I will empty the water on the ground and you will go thirsty until we reach a Christian village,” they still refused. I ate an excellent meal, drank all I wished, then kept my word and emptied the water container. They still thought I was joking nd for several hours we talked and laughed; at last we rolled up our Valensas (Macedonian hand woven heavy woolen blankets) and prepared to sleep.

All was quiet for a short time, then the girls began to whisper among themselves- they were hungry, but worse, thirsty! I pretended to be sound asleep, snoring loudly; finally my cousin poked me and pleaded with me to get some water. I “woke up” but told them that it was against Turkish law to disturb a Turk after he has gone to bed.

Finally their tears and pleading prevailed over my better ,judgment. I left the hut and went to that of our benefactor; he was ready to shoot me but finally he, too, felt sorry for the girls and gave me water for them. They drank it greedily and all agreed that Turkish water had a flavor far superior to that of our own town!

The caravan reassembled early in the morning and we proceeded to Sarovitch where we took the train for Monistir-Bitolia. Pusha remained as near me as she dared and before she said good-bye, told me to remember where she was, an open hint to write to her. I felt foolishly shy and ignored the remark.

I was again escorted back to Turia- Kragna after having completed my examinations with excellent reports. My uncle, as always, praised my work and told me what a brilliant and prosperous future I had in view.

Uncle Dimitri had, during the year, married for the second time. His new wife was from a neighboring town, Abdela; she had been employed as a teacher in the Romanian School at Turia-Kragna. This woman had a sis- ter who had been married to the most prominent citizen of Abdela, she was now widowed with two daughters, one very young and the other about my own age, she was at a loss to know how she would bring them up alone. My new aunt was a very kind person and requested that Uncle Dimitri allow her sister and the children to come to Turia-Kragna to live with them; he, of course, consented.

My step-aunt seemed to be most particularly interested in the older girl and treated her more like a daughter than a niece. I also noticed that I was being treated with unusual kindness, too, they did everything to prompt me to interest myself in this young girl, Maritsa Damashoti. My uncle’s wife would visit at our house and talk of nothing but Maritsa’s goodness, her beauty, her intelligence, she would throw out a few hints regarding the fact that Maritsa had now reached “marriageable age.” She assured me that she looked upon Maritsa as her own daughter and wanted her to make a suitable marriage. Maritsa’s real mother, on the other hand, was more impatient and had a friend of her come openly to me and speak for Maritsa.

I had to be a diplomat because of my uncle; I put them off by saying that until I graduated, I would not think of being engaged to anyone.

My Uncle Nicola (another sharp- shooter and a keen judge of human nature and character as well) knew what the two women were trying to accomplish; he told me that I would be a fool not to marry Maritsa, especially as Uncle Dimitri looked favor-ably upon the match and thus I would be “royally taken care of and would never have to worry about earning a living”.

“But I don’t love her,” I interrupted. “You’ll learn,” Nicola said, with a flourish of his hand.

Maritsa’s mother lived next door to my Uncle Dimitri and whatever she needed from his pantry or cellar, she took. All summer long she was busy preparing special sweets for me to take when I returned to school. The time for departure arrived and she and Maritsa presented me with enough delicacies to last the entire year. They filled one whole trunk!

A strong sense of duty regarding my “social position” and loyalty to my uncle were uppermost in my feelings as 1 said good-bye to them. Yet I could not imagine me without Pusha, she had become very dear to me. Life with Maritsa would be un- bearable even though she was ‘correct’ for me, as my cousin would clearly classify girls as “correct or incorrect.” I was actually overjoyed at the thought of being away from Maritsa and my other relatives for an entirely too short school year. I was looking forward to a period of freedom, a time in which I would have to think only of Pusha and my studies already I was trying to formulate what I would say in my first note to her!

(To be continued)

Responses