Finding Deep Roots in a Vlach Village

by Cheryl Pappademas Berman

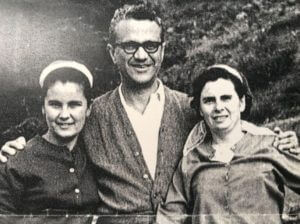

In 2019, after my mother passed away, a box of old family photos from her apartment came into my possession. Among them were several photos of a trip my parents took in 1963 to Samarina/Grevena, Greece. These photographs, taken with the then popular Kodak Instamatic camera, struck several nerves in my entire being. My parents were in their early 40’s and my father was standing with cousins, aunts and uncles that I knew nothing about. I was moved to tears wondering if any of these people, posing with my parents, were still alive, still in Greece. Would they be interested in connecting with me? Why didn’t I know more about them?

Samarina/Grevena, Greece is the homeland of my beloved paternal grandmother, Vasiliki Kopanos. She passed away in 1974 and now, fifty years later, looking through the photos, I found myself haunted with a desire and deep love to identify and hopefully connect with family members in Greece.

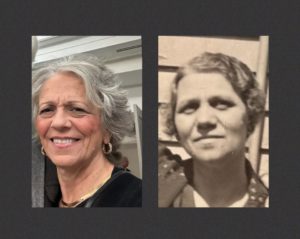

The above black and white photograph was put on a Samarina Facebook page and within a few months I connected with the daughter of one of these women.

Feeling quite optimistic I hired a Greek language teacher and began the revival of my language skills. Learning my grandmother’s first language was always important to me but over the years since her passing, much of those skills went dormant. However, through a variety of documents and stories I collected from friends and family, I learned the Greek language was not her first language. Aromanian was the first language of my great-grandparents. My grandmother was bilingual in Aromanian and Greek at a very young age. They were Aromanians/Vlachs, true nomads of the Balkans in the mid to late 1800’s.

The year was 1898. In the small mountain top village of Samarina located in Macedonia, Greece, Vasiliki Kopanos was born. She was the 4th daughter of five born to Agoritsa Kiskinos and George Kopanos. George herded livestock and the family seasonally moved between mountainous pastures and lowland areas in the Pindus Mountain Range. They raised their daughters in the most traditional ways of Aromanian/Greek cultures.

This is where my grandmother’s story began. She is my beloved Yiayia, “maea amea” and she was my best friend.

Times were very challenging and often grueling in the early 1900’s. The political landscape of Greece and Albania were extremely unstable. Borders were frequently shifting. The early 1900s brought much pain and suffering with Ottoman rule slowly on its way out and nationalist ambitions threatening the northern part of Greece. For my great-grandparents, raising five daughters was challenging in a patriarchal culture. Even though women were seen as an economic asset in the Vlach culture and there was no economic dowry system as was for the Greeks, times were tough. It was 1911 when a Greek sponsor from America stepped forward to help my great grandparents bring two of their daughters to America. They accepted his offer. This was seen as a chance for a better life.

In a matter of days my great-grandparents were faced with not only an opportunity for a better life for two of their children but also a dreadfully painful decision familiar to many Aromanian/Greek families at that time. Which two daughters would George Kopanos take on an unknown journey to America? I can only imagine the anguish in these discussions. Some of the considerations were age, beauty, willingness of the child, and possibly above all, marriageability. At that time it appeared my grandmother, Koula, (her lifelong nickname) aged 15 and Menia, aged 12, were the best choices. My great grandfather’s plan was to work on the railways, send money back to his family and arrange the marriages of his two youngest daughters over the next few years before returning to Greece.

In 1911 prior to departing from the Port of Patras, my great-grandfather and his two daughters said their goodbyes to family. The first part of the journey from the village was traveling on a pack mule or donkey over mountainous, unpaved paths and dirt roads. The journey was slow, uncomfortable, and potentially dangerous due to the terrain and the lingering threat of the brigands, which was a known issue in rural Greece even into the early 20th century. Once they reached Ioannina the journey to Patras had more established transport. The transport likely continued by horse drawn carriage or wagon. Patras was a major port for overseas immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At that time the average Atlantic crossing on a steamship was about twelve days.

They boarded the SS Martha Washington on May 29, 1911.George, Koula and Menia were herded along with many others to 3rd class steerage. Fear of the unknown was ever present. The living quarters of hundreds of emigrants on this twelve-day journey were packed closely together. Twelve and fifteen are very tender ages for young girls to leave their mother and the only homeland and languages they ever knew. This was especially true for those that lived in small mountain villages like Samarina, far from the modern world that was emerging elsewhere. Both girls were filled with unimaginable loneliness and broken hearts to leave their beloved mother and sisters. They did not truly understand what was happening. They had no idea what was ahead for them. Would they ever return to their village?

Every morning George, Koula, and Menia awoke to the smell of foul coal smoke, poorly prepared food, unwashed bodies, vomit, waste, vermin, and decay all mixing into a powerful, lingering odor that could not be escaped by those in 3rd class steerage. Passengers who were seasick often had nowhere to go, and sanitation was virtually non-existent. Major health threats included contagious infections like cholera, typhus, and measles, as well as chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis. No one in steerage was immune to these diseases.

Midway through their journey, young Menia became ill. With so many diseases on board, their father was unable to diagnose her illness nor was sufficient medical treatment available. Koula and George stayed by Menia’s side day and night as her condition worsened. As she vigilantly sat with her sister, Koula revisited in her mind their final farewells to their mother and three sisters not knowing if or when she’d ever see them again. She could only imagine hope for a better life outside war-torn Greece.

Young Menia was not only Koula’s sister but her confidant and best friend. They were to be side by side every step of the way in this new chapter of their lives. Koula was distraught, as she and her father were acutely aware Menia was going to die before arriving in America. For Koula, the ocean crossing was already filled with fear, distress and heartache. Koula and her father stayed by Menia’s side, trying to disguise her illness as fatigue because those that were very ill were often moved to a designated area in the steerage. They both knew her death was imminent and they wanted to be with her in those final moments.

Many weary souls on board traveled completely unaware of what lay ahead. Koula could not comprehend completing this voyage without her sister. Third class steerage was filled with frightened women and children in soiled embroidered village dresses and anxious men in worn wool clothing, all dreading the possible loss of family members to disease during this voyage. Menia held on tight to Koula’s hand from her hammock. For Koula, the humming noises of multiple languages and dialects blended into unrecognizable sounds. She tried to focus on these sounds to drown out the pain of knowing her younger sister’s death lay only moments away.

George and Koula prayed over Menia but within minutes of their prayer’s end, Koula’s father realized his youngest daughter had taken her last breath and he was overcome with grief. Koula, too, knew the pain that would follow this devastating loss. She knelt beside her younger sister and sobbed inconsolably.

It was customary, when at sea, to bury the dead in the depths of the ocean. Word spread quickly through the steerage that another passenger had succumbed to disease. It was not long before two crewmen came forward to remove Menia’s body from her hammock and take her to a designated area of the ship where bodies could be respectfully held until burial. Koula and George were permitted to wrap Menia’s slight frame and frail twelve-year-old body in one of the traditional homespun village blankets their mother had made for their journey before the crewmen removed her. Koula and her father, along with all the other passengers in steerage, watched as Menia’s body was moved to the designated area of the ship where the bodies awaited burial.

Burials at sea were set for early morning as the sun was rising. Neither Koula nor her father slept that night. There was a Greek priest on board who was from one of the northern villages in Epirus. He officiated the burial for all those being buried at sea that day. The following days were very long and this loss would endure in their hearts forever.

Now more than three-quarters of the way through their journey, from the upper deck levels and through many portholes, the reigning and imposing Statue of Liberty came into view. This was an impressive site for all on board. The statue represented a new life, the American dream, freedom from oppression, opportunity and hope.

The ending of this part of their journey also carried with it sadness of another life now left behind. The ache for family, homeland, native language and the fear of not being able to carry on religious commitment and traditions weighed heavily in the hearts of many. Fear of medical examinations with the prospect of deportation, discrimination, prejudice, and xenophobia also brought worry as the New York harbor came closer into view. Koula’s dreams of her new life with her sister were never to be fulfilled.

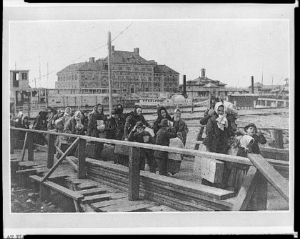

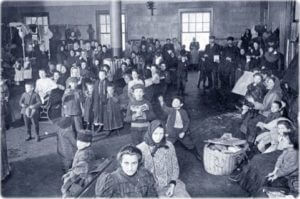

Passengers in steerage were not allowed to land in Manhattan. They were ferried from the steamship directly to Ellis Island and herded off in groups with tags pinned to their jackets or collars. Ellis Island was intimidating in many ways. It felt like it was part courthouse, part hospital, and part examination room. Doctors watched the movements of passengers closely and placed medical chalk marks on coats of those identified with possible illnesses. Koula stayed very close to her father for fear of separation.

George Kopanos knew no English but held on to their documents as if sacred. Within minutes, however, he was ordered to hand Koula her papers. For the initial entry for medical and legal inspections in the Registry Room they were required to separate. Koula was frightened at this separation as she did not understand what was happening nor did she understand a single word spoken. Her father calmed her and told her they would meet up in a few hours. These were likely the longest few hours of her life.

Finally they were reunited and continued on to the next phase of travel. They boarded a second ferry from Ellis Island to take them to Manhattan. Arriving in Manhattan, a city with concrete buildings and noises of all kinds, Koula kept her head low, followed her father and they made their way to the appropriate train station following others headed to New England. They finally arrived at the appropriate station. Exhausted and hungry they boarded a train bound for New Hampshire.

After several stops and route changes they arrived in Woodsville, New Hampshire. Woodsville was a village within the town of Haverhill that boomed into an important railway town and junction after the railroad arrived in the mid-19th century. Their sponsor was a distant cousin living there. They were welcomed, fed and had a chance to bathe and sleep. Koula was in a bit of shock but trusted her father completely to care for her and make the right decisions. All the while her thoughts returned to Menia and how she so desperately wanted her to be on this journey with her. She kept all those thoughts to herself.

Within a few weeks, her father began working on the railways for income to live on and to send funds home to Samarina. Koula kept busy cooking, sewing, and working at the small farm where they were staying. In less than a year, they moved to Nashua, NH where there was a fairly large community of Greeks and Vlachs. There were two Greek Orthodox churches within one neighborhood. For the first time since leaving Greece, Koula started to feel the slightest sense of belonging, a slight sense of home. Communication, faith and companionship with immigrants from her homeland and many from Samarina and surrounding villages that spoke both Vlachika and Greek were a comfort.

Koula was able to make a few good friends in her new surroundings. She was shy, fearful, and maintained her dedication to Orthodoxy. Soon she would be approaching her 18th birthday. She knew her father would arrange her marriage and she would have little or nothing to say about it. Shortly after her 18th birthday she was betrothed to Demitrios Pappademas, 16 years her senior. He was a Vlach born in Trikala and may have also had relatives in or near Samarina. His death record (USA) indicates he was born in Thessaloniki and settled with a brother in Trikala. In hindsight, it was actually a blessing that Koula married a Vlach/Greek and stayed within the religious realm of Orthodoxy.

Now Koula at age 18 was a νύφη/nveasta (new bride) with very little prior exposure to men in the ways of love and marriage. My sense of her married life, according to my aunts and uncles, was that she followed strict customs, listened, prayed, obeyed, worked, and had children.

Over the next ten years, she gave birth to six children. Life presented its challenges. She lost two children to illness. George Demitrios, born in 1919, died of double pneumonia in 1924 at the tender age of 5. The second loss was Nicholas Demitrios, born in 1920 who died in infancy, cause of death unknown. These losses were devastating. My grandmother and her surviving children never spoke of them. When I was in Greece in 2025, over 100 years after these losses, the family there had no idea that two of her children had passed away.

They remained in Nashua for the rest of their lives. My grandfather had a barber shop and my grandmother worked in a cotton mill. She worked a 2nd or 3rd shift since she still had children at home. Conditions in the mill did not promote good health. The number of years she worked in the cotton mills is unclear but she suffered many health issues with her lungs, heart and had asthma. She needed to stop working in her early forties and just a few years later in 1943 her husband died of a coronary embolism. He was 61 and she was 45 with four children at home. Thomas was the youngest, age 9, Afrodite was 13, my father George was 19, and Stella was 25 and soon to be married. It was a very challenging time. My father, who had been working part time and attending business school, left school to become the head of household.

My father took care of his siblings until they were old enough to finish high school, work, or get married. In 1947 my father, now married, bought a duplex on Lincoln Avenue, in Nashua, NH. My oldest brother was already 5 when I was born in 1953. My grandmother lived upstairs with her two adult children yet to be married. It was a great setup. Yiayia was my best friend, only one flight of stairs away without having to go outside. I spent a great deal of time with her, had sleepovers, and listened endlessly to her stories, poems and songs. The happy memories she shared with me were always about Samarina and Grevena. They were vivid memories and always brought a smile to her face. I was made aware at a very young age of the pine tree growing in the roof of Megali Panagia church. The festivals and special holidays were something she shared with me repeatedly. Those fond memories kept her family alive in her heart for the rest of her life.

Yiayia always had a small basket of medicine bottles on the kitchen table. Since she left the cotton mill at age 43 due to lung and heart issues, she had developed several maladies that required prescription medications. On holidays my father and uncle would carry her downstairs to celebrate with us or we’d all go upstairs to be with her. She never went out. She was a loving grandmother. We always found plenty to do. We spoke Greek/Vlach/broken English. We watched TV and played “ξερη” (xeri), a fun card game. We cooked together and laughed a lot. I still have many of her old recipes, not in her handwriting but handed down to my mother and then to me. She also taught me how to crochet. She made me many crocheted items without a pattern. She would look at a magazine photo that I’d shown her and soon I was wearing it. I still have every treasured piece in my cedar chest. I suppose one could say those 15 years of being raised in all the traditional ways of the Aromanian and Greek cultures before leaving Greece was my great grandmother’s legacy to her daughter Koula. A legacy certainly to be proud of.

Yiayia died in 1974 at the age of 75. It was not her maladies that took her. She unfortunately tripped on the corner of a carpet with her walker, broke her hip and died five hours later. This was my first and most devastating experience of loss. I was 21 and a junior in college. My heart is still broken 51 years later.

Over the course of the last 5 years I have obtained birth and death certificates, Ellis Island registration documents and identification of several family members in the photographs I received in 2019. My love for my grandmother, and my love of Greek/Vlach culture created a bond between us that is immeasurable. Her story is my homage to the woman I called Yiayia and I am honored to share some of her life experiences with you. This was something she was unable to do. I am her voice.

Over the last 2 years I have been fortunate enough to locate family members who desperately wanted to meet me. I made my first trip to Samarina in May 2025. I was able to fill a lot of gaps of information firsthand from cousins, nieces, and nephews. Most interesting to me was that there were in fact, five Kopanos sisters in Samarina. My father and his 3 siblings were told there were four sisters. I was told by my yiayia that it was her and her father who made the journey to America. Young Menia was never mentioned in America. The Ellis Island registration document that I located 5 years ago only listed Koula and George Kopanos as registrants. We never knew there was a fifth sister. Such a painful secret to never speak of or process the loss with family.

There are likely many similar stories out there not only of Vlachs and Greeks but of families from all corners of the earth who emigrated to America for a better life. I hope this story has touched you in some way, bringing to mind your own loving reflections and appreciation of your family’s ancestral story.

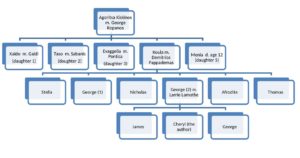

Cheryl Pappademas Berman Family tree

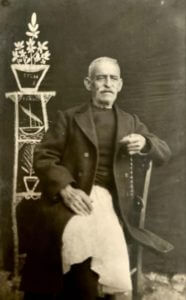

Vasiliki “Koula” Kopanos. 1943

Author’s note: This is part one of my grandmother’s story from Samarina 1898 to her community in Nashua, NH 1974. Part two is in progress. It will focus on her impact on my life and how the impact of my Aromanian ancestry has brought me to this place. I hope to publish it soon.

End Part 1 © Cheryl Pappademas Berman 2026

This is an inspiring beautiful journey of ancestral discovery & understanding; which ultimately leads to healing and a deeper knowing of the self. And my MOM wrote it!! WOW.

Cheryl’s story of her family’s journey to America was heartwarming to read. I felt like I was on the boat with her grandmother when her sister died. Cheryl did not list these events like in a document; they were interwoven into the fears and ambitions of her Greek family’s challenges to survive so far from their native home and relatives. How wonderful that Cheryl had the loving opportunity to know and love her grandmother.