Haralambie George Cicma Autobiographie Part VI

(Continued from last issue)

PART VI

NEWPORT, NEW HAMPSHIRE

I took the train from that despised and detested town and traveled toward New Hampshire and I found that the views, especially the moun- tains, reminded me of Macedonia. My first impression of Newport was that I had been transported back to Turia-Kragna; the town was practically surrounded by mountains and a brook divided it into two parts!

My first cousins, Atha Vaeni and John Barjuma (this is not the same John who befriended Pusha and me), were waiting at the railroad station to bid me welcome and to escort me to my new home; we walked about ten or fifteen minutes, to their cottage on Sunapee Street—this faced the brook and the view was delightful.

The eight other young men who lived there had been very busy, preparing a scrumptious Macedonian feast and making plans for a celebration; after our meal we were joined by fourteen more young men, all of whom were from our own hometown. We renewed old acquaintanceships and had a wonderful time, singing Romanian songs and dancing until very late. Most were bachelors but a few were engaged and, by our custom, this means that you are already half married; many had come to America to make money so that they could afford to return home and marry. They were happy working in the woolen factories, the sawmills and the shoe factories; all were very industrious and were, for that particular era, making most excellent pay.

In our cottage there were Tom

Stambaki, Sam Economo, Jim Hueaza, George Cutifit, John Condonine, Jim Ghotti, Costa Catsanu and his brother, also my two cousins; we lived to- gether, each helped pay the rent, kept their own room clean, did their own laundry, and took turns cooking the food. Atha was the undisputed head of the household. He tried to teach me how to cook so that when he went to the old country to get married I could take his place. Under his tutelage, I became quite a decent cook.

I was nostalgic for Turia-Kragna after seeing so many of my country- men, and more especially from the physical appearance of the little town, but as soon as I was settled, I asked where, when and how I could get a job. They all advised me not to be in a hurry as there was plenty of time for work and they suggested that I “take it easy for a while” and learn more about the American way of life.

Cousin Atha was employed as a foreman in the Guild Woolen Mill, about two and a half miles from town, he thought I could be placed in his department eventually but, because I had been so ill and was unaccustomed to the New Hampshire climate, he said that it would be too cold and snowy for me to walk the long distance to the mill in the winter—also the pay was small and the work dirty; these conditions might cause me to have a relapse. He did ask John to find me a job in the shoe factory in town; he thought this work would be easier for me to learn and it was also cleaner and paid better.

I took their advice and loafed for a while but, being anxious to accomplish my goal, I did not feel that it was fair to waste any more time. My cousins and the others were always telling me that in order to get a good job I would have. to wait several weeks or perhaps months. The days passed very slowly and were so boring that at last I got up at five o’clock one morning and begged Atha to take me with him to the woolen mill.

He objected strenuously but I finally broke him down and he let me tag along. Once there he tried to explain, in his broken English, that I was his cousin and needed a job. This factory always needed help as it was so far from town that no one liked to walk there, especially in the cold weather. They told Atha to try letting me run the pressing machine.

My pay was to be eight dollars a week for working ten hours a day, six days a week. I accepted this gratefully and Atha spent the day showing me how to operate the equipment.

I was happy to have this job. It was clean, the pay was quite good for the times; in a few weeks I became an excellent worker. I was trying hard to save as much money as possible; I did my own laundry, helped the others with their rooms and often took over someone’s turn at cooking; I did not spend one single unnecessary penny.

John Barjuma and most of the others were furious that I had taken a job so far from the house; they especially felt that anyone with such an excellent educational background and who had enjoyed the social position which had been mine in Macedonia, should not be doing menial labor. I had by now quite overcome my pride regarding my former life and this time, in spite of all their criticisms, I was determined to keep the job and to do my best at it.

With the exceptions of my cousins, Atha and John, George Cutifit and Tommi Stambaki, all in our house had been shepherds or farmers in Turia-Kragna and, coming from the working class, had very little education. George had completed the Romanian Schools and Tom Stambaki had attended the Romanian Commercial School at Janina for two years. Tom quit school to come to America and “make a fortune.” This young man really didn’t have to labor in the factories as his father was wealthy, he owned two grain mills and several farms and employed several people; Tom was the only son and he could have had an excellent life in Romania. As it turned out, he was the most stupid boy in the house.

The time was rapidly approaching for Atha to leave for Greece and I persuaded him to teach me to use some of the other machines so that when he left I could take his place (my real reason for doing this was that I wanted the extra money he was paid each week). I could run every machine in the finishing room in about four weeks and I was very proud of this accomplishment. Atha also worked overtime almost every night until eight or nine o’clock and this gave him even more money; at first he didn’t want me to do any extra work as he thought I was not yet strong enough for it; but I finally convinced him that I was now perfectly well and able to accomplish whatever I decided to do in this country. I was through taking it easy and listening to the advice of others, I was going to work long, hard, and earn enough money to go to school. My cousins respected me because I had acquired such a good education in Macedonia but they tried to convince me that I would be foolish to attempt to continue to study here. They could not change my mind and I told them that I had already wasted far too much time. Atha finally capitulated and asked that I be allowed to work overtime also; I now put in twelve to fifteen hours a day and my pay was ten to fifteen dollars a week (all mine, no taxes)! Friday morning we went to work at six o’clock and we worked straight through until Saturday noon.

My countrymen were good workers, but they couldn’t save any money, they spent it all—gambling, playing cards and/or drinking. My cousin John did not really need to leave Macedonia, he was engaged to a very fine young lady there, his father had many sheep and goats and owned several farms so John was well taken care of, but he wanted to become independently wealthy” so he came to the land of easy money. John had a good job in the shoe factory, he worked hard and made a larger salary than any of the others. He never saved a penny as he both drank and gambled.

John’s father kept writing to him, offering to send him the money for his fare home so that he could marry, they all loved his fiancée and didn’t want the engagement to be broken. John refused all offers and continued his merry but, when Atha was preparing to go back to the old country, John became so emotional that he started to cry and declared that he wanted to go with Atha. About a year earlier John had made up his mind that he would reform and would save the money to go and claim his bride. He made a bargain with Atha; he would give his entire pay to Atha and would be allowed only five dollars a week for spending money. In this manner Atha accumulated almost nine hundred dollars for him; John had to go to the dentist and while he was there, he decided to have his own, perfectly good teeth removed and gold teeth put in; there went the whole nine hundred dollars! Atha was so disgusted that he refused to have anything further to do with him. John was, of course, broke when Atha was planning his trip.

I had, at that time, saved up about two hundred dollars and I offered to lend it to John so that he could go with Atha and claim his bride. John refused, saying that he would work even harder, would stop drinking and playing cards; he would prove once and for all that he was a worthwhile person. He was, apparently, completely reformed and soon had saved about four hundred dollars, then one day he began to play cards again and lost the entire amount. No more reformation, the same old John returned.

A month later, Atha wrote him and said that he had visited John’s promised bride and had told her that she should no longer wait for John as there was little or no hope that he would ever marry her. The girl in- formed Atha that as long as John was alive she would wait for him, she loved him in spite of his faults and his neglect. John was very upset and when I returned from work that evening, he started to sob and told me the whole story. He begged me to lend him the two hundred dollars so that he could go back and get married. I’ve always been a soft-hearted slob, so I let him have the money, but we all made sure that he got on the boat.

My mother wrote me a few months later, asking that I send her some money for food; I had no savings at that time so I sent her a letter explaining that John owed me two hundred dollars. I also enclosed another note, addressed to John, asking that he give her food and that he repay the loan, gradually, to my mother. She wrote back that she had gone to him, given him the note and asked for some grain and a few dollars. John brushed her off, empty-handed, told her that I was crazy, he didn’t owe me anything! So much for loyalty from relatives, also for generosity.

The only day I had to myself was Sunday, I usually spent it in the small park opposite the Methodist-Episcopal Church. I would get up just as early as usual and, taking my books, would stay there all day, trying to learn English via the French Method! I had tried previously to do a little studying before going to work but just as soon as the others realized what I was doing, they took great pains to disturb me as much as possible. It soon became evident that my learning English was not to be of much value to me, as soon as I tried to use it in the factory, they would all look at me warily or amusedly and I was never sure whether I had insulted someone or had said something stupid. Most of the English I heard was slang, I wasted many valuable hours looking up these idiomatic expressions and was often more confused after translating them than before.

I had not, in spite of these adverse conditions, given up my dream of furthering my education. I was unable to learn much at the house or on my Sundays in the park; I finally conceived the idea of memorizing a certain number of words daily. I wrote the English words and their French equivalent on a piece of paper and tacked it on the wall in back of my machine; one day Mr. Fairbanks, the owner, saw them and asked what I was doing. I explained, as best I could, my hopes and ambitions; now he understood the reason for my wanting to work overtime. He said that he was proud to know such an ambitious young man and that he wished me success in all I attempted.

Our severest weather came in February. One day it was so stormy and cold that it was unfit for any human to be out. Naturally this was the day that they asked me to remain late to finish some work. There was a train for Newport at nine that evening and I planned to take this, however it was nine-thirty before I completed the work: I started the long walk back, the snow was up to my knees and I had to go slowly; I reached home after eleven o’clock and, as usual, the kitchen door was open, the fire had been extinguished and my supper was frozen (I now firmly believe that these were the original TV Dinners, I didn’t like them then and I still will not permit them to be brought into my house). My whole body was numb with cold and I was so disgusted with their stupid tricks that I sat down on the steps and cried. Later, I went to my room and tried to warm myself by rubbing my body with a towel, this helped a little and I crawled into bed, vowing that I would no longer live with these people.

I got up the next morning at four-thirty as usual but I didn’t build the fire-I only poured more water into the stove and went out, leaving the doors and windows open. I was so hungry that when I arrived at the factory I was unable to work; as soon as Mr. Fairbanks came in, I went to his office and began to tell him my story, my English was not enough to cover the situation but I did the best I could. Finally, I took him into the factory and showed him a pile of rags I had discovered in a little used corner and tried to make him understand that I wanted to sleep there, this he comprehended. I also succeeded in telling him that I was hungry, “No supper, no breakfast,” I kept repeating. He took me to a small restaurant which was run in conjunction with the factory and gave me a hearty breakfast.

He could not permit me to sleep in the factory as it would not be healthy, he said, but he did arrange for me to have room and board with one of the mill’s firemen who occupied one of the factory houses. Thus, for the first time since my arrival in this country, I was to stay in the home of an American couple.

Most employees at Guild Woolen Mills were Finns, although there were a few Frenchmen, Greeks and Romanians. The bosses and the firemen were all Americans. Mr. Fairbanks advised me not to return to Newport that night, he bought me a pair of pajamas and I was formally installed as a boarder. The quiet of the place was like heaven to me, the only disagreeable feature was the American food, it was good and wholesome but I was not accustomed to it. This peaceful interlude lasted a whole week.

My Romanian “friends” began to worry about me, thinking perhaps I had been killed by a train; they came to the factory office to ask Mr. Fairbanks where I was. He told them that he had found me a good place to stay and that he considered they had been unkind, uncouth and unfair to me; he eventually, after much pleading, let them talk to me.

They begged me to come back with them, vowing that they would never treat me badly again. I told them that I had had enough of their idiotic pranks, it was no joke to work hard all day and then go home to a frigid house and frozen food. I was fully determined to remain in my present place but finally I returned to Newport as Mr. Fairbanks felt that I would be happier there until I learned more of the English language.

I managed, by scrimping and saving, to accumulate about three hundred dollars by June 1914, I never spent a cent unless it was absolutely necessary. The Finnish workers in the mill went out on strike by the end of July, requesting an increase in pay. Their claim was refused by management but the newly formed Union backed them. They tried to tell me not to come to work the next day. I did not want to lose a day’s pay so I replied, “I got to work.” This made them angry and they assured me that I would get my head knocked off if I did work!

I appealed to Mr. Fairbanks and he tried to explain about the trouble among the workers and what it meant, he also told me that I could, if I wished, continue working. At home, I told my friends what had transpired and they verified the seriousness of the situation and advised me not to return to work as it would be, indeed, exceedingly dangerous.

I remained away from the mill the next day but on the second day, Mr. Fairbanks sent a man to bring me to the factory to help them finish some work; I went and did what was required, these bolts of cloth were sent out and then the mill closed, all operations were suspended until the strike was called off.

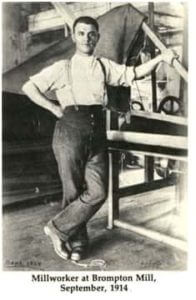

The strike lasted more than a month, during this time I tried to get another job; I visited every factory in the area but there were no openings, at the Brompton Mill in the center of the town I was given some encouragement, the foreman promised he would notify me as soon as there was a job available. The Guild Woolen Mill reopened and many returned to work but I was not called—my working to complete the orders had given me the classification of “scab” with the Union and I was the last person to be put back to work.

I was fortunate to have been called to work at the Brompton Mill, the foreman kept his word and this work was not only more convenient—no more long walks-but I actually had to work only five days a week and had every Saturday and Sunday free.

I still made my Sunday morning visits to the park with my books. One Sunday, an elderly man sat down near me and began to talk, he asked if I could read English and I replied that I did not read very well but I was trying hard to learn. He gave me a Sunday School paper and I tried to read it, I understood that it was a passage from the Bible.

“Do you go to that church?” I asked, pointing to the Methodist- Episcopal church just opposite the park. “Yes, I do,” he answered. “Well, are young people allowed to go to church there?” “Of course, why do you ask?” “Well, I have seen only old people go in there, once in a while a young person goes with them, but never alone,” I explained.

He began to laugh and asked, “Would you like to accompany me this morning?” I was only too happy to do so and we attended the service together; later he introduced me to the minister and many of the people there, I was surprised and delighted to see Mr. Fairbanks and he was very glad to see me.

This was my first real experience with American people and American churches. I enjoyed it and after that day I went to church quite regularly. I could not do otherwise as the old gentleman persistently brought me to every special meeting and all revival services as well as regular Sunday ceremonies. I grew to love this kindly man and started to look upon him as my “American father.” Years later, I learned the story of this fine man. He had been a well respected, hard working construction foreman who became an alcoholic; addicted to such an extent that he lost his position, finally he was unable to do any work and resorted to singing in saloons as a means of securing liquor. One very cold winter night, he had made his rounds and, unfortunately, passed out. He was found by the minister of the Methodist-Episcopal Church, almost frozen, he was taken to the parsonage and they nursed him through the ensuing pneumonia and kept him there until he was completely rehabilitated. He never returned to his former habits and was now the quiet, well liked gentleman who had taken me to church.

The summer passed pleasantly and after Labor Day, 1914, the public schools reopened; both the minister and my “father” urged me to go to the evening classes at Newport High School to try to learn more fluent English. They took me to the building on opening night, introduced me to the superintendent and asked him to help me as much as possible.

The people there were mostly foreigners and the majority of them were illiterate individuals who could not read or even write their own names. The system used to classify them was to send them to the blackboard to sign their names, most of them put an “X” as they knew no other method.

I was in a group which was to be tested by John McCrillis, an upper classman in the high school. He was the son of one of the wealthiest men in America, but at that time I was unaware of this fact. He was simply dressed, a sweater and well-worn trousers. From his appearance I thought him to be the son of one of the farmers from the out-skirts of Newport. When he called me to the board, I stepped up and wrote my name legibly; he naturally understood that I was not so ignorant as the others and he told me to sit at his desk while he made a few more simple tests and classified the students. Several school books were on the desk; one was a French Gram- mar, which I picked up and started to read.

At the end of the session, John asked me questions about my life and education. I tried to tell him in French, but he said that he was only beginning to learn that language. In my rough English I told him that I had graduated from the Romanian Commercial School and had spent five years in the Turkish Lyceum; I tried to convey to him that I had the knowledge, and that I needed only the language with which to express it.

He invited me to go home with him to meet his mother and to have a further conversation. “My father’s house is the one right next to the library,” he said. “My father is in Chicago, so I’ll drive you there in his car and bring you home later.”

I was astonished to find that he lived in such a house, one of the most beautiful in Newport. I began to realize that he must be very well to do; I was surprised and impressed by the way in which the wealthy mingle with the poor in America, and also by the way that rich boys do not take it for granted that what belonged to their parents belonged to them. In Europe, anything possessed by the family was the possession of all in contrast with the American tradition of everything being the exclusive property of the head of the household. John’s mother received me graciously and told me to visit with her son whenever I so desired. I spent about an hour and a half there and before I left I had agreed to coach him in Mathematics and French and he was to help me learn the English language. He came, nearly every night to the Brompton Mill, took me to his home and we studied together. He furnished me with a few elementary English books and supervised my study.

I had been going to the movies regularly before I met John and I was very much interested in the serials they had, wild west and all that sort of thing, so on my movie nights I refused to go home with him. John’s father came home two weeks after our meeting. John, as usual, was at the mill to get me and he said that his father wanted to meet me. I explained that this was my movie night and I had to see how the serial was going to end! Poor John, he said that they would be glad to wait until it was over and I could come to the house then. I walked to his home, arriving at about ten-thirty. I was introduced to his father, John McCrillis, Sr. He was a typical European type of person in appearance; he was tall, well- built, aristocratic looking, and had a large mustache.

Mr. McCrillis asked me where I lived, where I worked, how I liked this country, and what I wanted to do with my life. I told him that I worked in the Brompton Mills and he informed me that his father had established this factory and that he was now the sole heir and owner of the mill!

I was really impressed; I was in the house of my actual boss. I finally summoned up sufficient courage to tell him that my goal was to save enough money to return to a school and finish my education. He thought this was an admirable attitude and wished me well. He expressed his gratitude for all I had done for John and said that if I would continue to help him, they would do everything possible for me. I was there until almost midnight and finally John drove me home.

After this, I sacrificed all my movie night except Saturday when the serial was on—and John and I continued our mutually helpful application of knowledge. The whole family was very kind to me, they took me many places and all took turns correcting my English!

On Christmas Day, John waited for me at the church after the service and asked me to come home with him for dinner. I had never been to a dinner in a rich American home so I offered many weak excuses for not coming. He insisted and I finally had to tell him that I could not come as I did not know how to eat in the proper American fashion. He roared with laughter and said that was no excuse, all I had to do was to follow his example and I would be all right. His mother and father were happy to have me there, we were soon seated at the table, every food was new to me, but I watched John carefully and managed quite well!!

We sat in the living room after dinner and his father and mother began to talk about my future; they had decided that the best place for me to attend was the Kimbal Union Academy which was situated a few miles from Claremont. Mr. McCrillis had graduated from this school and he was also a Trustee of the Academy. They asked me when I would like to start at this school and suggested that it would be wise for me to plan to enter at the next fall term. I had to tell them that, while I had been able to save some money, I would be far from able to start in the fall, perhaps the following year.

They explained that I did not need any money as I could work my way through; this was an entirely new idea to me because in the old country we had a strict, set curriculum and there was no time for work other than in the classrooms. Mr. and Mrs. McCrillis tried very hard to show me how this could be arranged but I could not understand it, nor could I even be convinced that such a thing was possible. John took me home at about six o’clock that evening and, every time I was there the following week, they tried to make me decide just when I would start school.

They invited me to have New Year’s dinner with them. I was very much surprised to discover that they had invited another young man, someone who looked very much like the man who picked up the laundry at our house. They asked me if I knew him and I said, “I think so, I think that he is our laundry man.” Everyone began to laugh and Mr. McCrillis said, “He is also a classmate of John’s.”

He explained that he worked and studied too, that any ambitious student could do the same thing. He had no father and his mother worked in the factory to support the other members of the family. The money he was earning now went partly to a fund for his future education and, when needed, helped defray the family expenses.

I was greatly encouraged to learn that it really was possible to work and go to school, but I was still unable to make up my mind to start before I had more money saved.

John and I continued our study arrangement and I began to under- stand the English language much better. I was with his family a great deal; in the winter we went to their camp in the country and in the summer I often took long trips through the mountains with them. They took me once to the older Mr. McCrillis’ birthplace; his parents had been poor and he had worked very hard with his partner, Mr. Brompton, to start and to make a success of the mills. Mr. Brompton died and left his share to John’s grandfather who in turn transferred the title to John’s father; by the time that I first knew him, Mr. McCrillis was considered to be one of the richest men in America. He was a respected and revered man, a member of the Town Council in Newport— his every word was regarded as law! They drove me out to the Academy one day in early June, it was beautifully located—at the top of a hill, overlooking the city of Claremont. They introduced me to the superintendent and, after hearing my story, he assured me that he would do his best to help me in every way possible. I received a letter from Kimball Union Academy in late August, 1915. In it, the superintendent told me what day to report to school and stated that he had secured a good room for me. He had also spoken to the English teacher about me and arranged for him to give me private attention.

I didn’t know what to do, I read and reread the letter and then hid it. I did not mention it to either John or his father. I had fifty dollars in the bank and I wanted to hang on to my job until I was sure of what was in store for me. I avoided John and his family as much as possible; a few days later John came to the factory to get me, but I was not there, he went to my house, I was out; he finally caught up with me and brought me to his home.

They asked me if I had received a letter from the school, I replied that I had not. They then told me that I was a very fortunate young man as everything was arranged for my entrance to the Academy.

I am still not certain just what lame excuse I gave them for not going, but I finally convinced them that I could not start at the present time. My real reason was that I did not have the courage to break away from my associations, my reliable work and I feared to take up life anew at the Academy.

I could read the bitter disappointment in their faces and, although they told me that I was losing the chance of a lifetime, my mind was made up and I was determined not to go. Gradually, they began to lose interest in me, they were no longer as pleasant to me; I had, in fact, lost their admiration and confidence. They said nothing more regarding my going to school.

(To be continued)

Responses