The Vlachs in Albania: A Travel Memoir and Oral History

My father left Albania in 1916, but even fifty years later he enjoyed telling me how difficult his journey to the United States had been. By this he meant not the seaward leg of the voyage, as other immigrants might, but the route on land. “Balkan” is Turkish for mountain, and it is notoriously difficult to get around on that peninsula. At fourteen years of age, my father had left the town of Korēė on horseback and crossed the snowy mountains of Macedonia, descending several days later into a Greek port in Thessaly.

He arrived in New York City and was so smitten that when his father returned to the Balkans, he defied him and remained here. Ubi bene, ibi patria. He taught himself to tend bar, worked in speakeasies during Prohibition and later in Mama Leone’s, and, except for a few brief stints in the humming wartime factories of New England, remained in New York for the rest of his life. After World War II, he considered going back to Albania, but, like the old joke about Philadelphia, it was closed; instead he visited Greece, where he met and married my mother.

We are Vlachs, Romance-speaking descendants of indigenous Balkan peoples and the Romans who conquered them during the second century before Christ. By retiring to the mountains, we survived two millenia of invasions by Slavs, Byzantines, Avars, Huns, Normans, Goths, crusaders, Turks, Nazis, and communists. In 1991, when the fog of totalitarian rule finally lifted from Albania, the Vlachs there were permitted to organize an ethnic society. The first conference of this new society was scheduled for April 5th, 1992, but my father had died fifteen years before, so it was left to me to complete the circle.

The return to Albania was considerably easier. A single phone call and a piece of white plastic, two by three-and-one-half inches, with green and black ink on it, were all I needed to get back to the country my father had left with so much difficulty seventy-six years earlier. It took him the better part of a month to get to America; it took me 17 hours to get back — ten hours aloft plus a seven-hour stopover in Rome. He braved bears, wolves, and brigands in the mountains and U-boats in the sea; for me, the greatest inconvenience was the boring in-flight movie.

I was one of a delegation of three American Vlachs traveling to Albania for the conference. On the propeller plane from Rome to Tirana we met another American, a representative of the Explorers Club who was visiting Albania to explore the suitability of the Drina River for white-water rafting (Get ready, Albania, I thought, Club Med can’t be far behind). I spent most of the flight at the window. The Adriatic, once a great sea separating the two great civilizations of antiquity, from the air seemed more like a very large lake. Perhaps I have studied too much history, but as we crossed it, I had the feeling that we were crossing a frontier — from West to East, from civilization to barbarism, from science to mysticism, from right to might, from prosperity to poverty, from light to darkness. Even as I strained to find Albania on the horizon, I knew it must be dark.

To my surprise, my first glimpse of Albania was not dark but bright — the clean white clouds that covered it; the beautiful light green of the inshore Mediterranean; and the golden shingle of the unspoiled coastline. But as soon as we were on the ground, the dark side of Albania prevailed and, reinforced by a steady rain, provided a dispiriting backdrop for the week’s events. My first sight as we landed was the dozens of cows and sheep that had claimed almost all unpaved ground in Tirana’s Rinas Airport, my first scent as we disembarked was their odor.

As we stepped onto the tarmac we were met by two somber officials. Although this is changing now, Soviet and East European policemen were once everywhere the same, as if formed in a single mold and then dressed in the same uniform — low-cut flared-leg trousers (in the parlance of the 1960s, stovepipe hip-huggers); epauletted shirt worn outside the pants, like a tunic; oversized round hat with a splash of Communist red above the visor — with only a change of colors and insignia indicating a change of country. Our hosts were wearing blue with red trim, and as we walked away from the plane one of them made like he would shake me down for 50 bucks for a visa. I followed my New Yorker’s instinct and laughed out loud. I had a letter of introduction from the Albanian Mission to the United Nations and ended up paying only the usual fifteen-dollar fee.

Rinas Airport is a landing strip and a modest control tower atop a building the size of a supermarket. The arrivals area consists of two bare concrete rooms; in the second and smaller room, two slabs arise from the floor like sacrificial altars. Since I had already traveled in Eastern Europe in the full gloom of communism, I knew these were for my luggage, and I braced myself for the usual thorough search. To my surprise, however, the woman in charge asked merely, “Anything to declare?” and when I said no, she waved me through.

The small parking lot was mobbed with Vlachs who had come to greet their three compatriots from America. This visit was our first attempt to renew formal links with our Albanian kin after almost a half-century of communist rule. If Americans are still rare in Albania, American Vlachs are nothing less than a novelty, and we were received very warmly. For a moment, the embrace of my community made me feel at home, but the fifteen-minute ride into Tirana brought me back to reality.

Albania is a land of superlatives, but unfortunately, since World War II most of them have been negative — the most repressive communist regime, the most isolated, the most militarized, the poorest country in Europe, the worst infrastructure, and so on. The poverty was obvious during the ride from Rinas Airport and figures soon confirmed what my eyes had seen. The official exchange rate in April 1992 was 45 leks to a dollar, but because there was little faith in the lek and much in the dollar, a far different rate prevailed in the open air of the plaza across the street from the state bank. The day I arrived the plaza was paying 82 leks for a dollar; as I left ten days later, the rate was 90; a week after that, it had reached 100.

View of Skanderbeg Square in central Tirana. Hotel Tirana on left.

At the time I arrived, a laborer earned about 800 leks a month (eight dollars) while a professional made roughly 1,200. I saw signs of the dismal economic situation everywhere. Most of the people were fairly slim — there simply is not enough food to sustain overweight Albanians. Also striking is the high rate of gum disease and tooth loss; indeed, at times it seemed to me as if the only people with good teeth were the police and the military, who must have received priority for medical and dental services and a balanced diet. Communists look after nobody if not their own.

The poverty was also evident in the people’s clothing. When I was a child, my mother used to send me to the post office every few months with a box of used clothing she had collected for our relatives in Greece, which was then in a bad way. Albanians are now receiving such packages from friends, relatives, and charities throughout the world, and in the odd mixture of well-worn clothing one sees more than a few fashions whose day has passed. And not just the clothing the world no longer has use for, but also a good portion of its older machinery, which is jerry-rigged and kept running against all odds. Indeed, it is a mark of Greece’s relative prosperity that many of its discarded automobiles and buses find a second life in Albania.

When I was in graduate school, it was in vogue to question whether there really is such a thing as a totalitarian society. Students who’d been subjected to no power greater than that of their well-to-do parents were routinely heard to say that even in Hitler’s regime, there was room for action against the state, which was itself “not monolithic but nuanced.” It seems to me that a society is totalitarian if its ideal is total control. Some societies live up to that ideal better than others, and in this regard, Adolf Hitler might have learned a few things from Enver Hoxha (pronounced HOE-jah), whose dictatorship reached so deeply into Albanian society that even those who detested him wished Comrade Enver a long life and toasted his achievements at the family dinner table every night. Hoxha died in 1985, passing his mantle to Ramiz Alia, who was apparently so shaken by the fate of the Ceausescus in 1989 that he took a small step back from Hoxha’s hard line, decreeing an end to government celebrations of Stalin’s birthday, for example, and opening the door to political pluralism; facing certain defeat in April 1992 by Sali Berisha, a cardiologist who helped found the new Democratic Party, Alia resigned. He was the last communist ruler in Europe.

The Hoxha regime was a sort of mass psychotic episode for Albanians, who were routinely fed this very sick man’s world view and forced to participate in his delusions and paranoia, which grew steadily worse over the decades. In a “Constitution” promulgated in 1967, even religion was banned; making the sign of the cross became a criminal offense with a penalty of three years in prison, and you couldn’t even exclaim “Jesus Christ!” The damage done to Christianity in Albania was brought home to me when I left Tirana with a group of young Vlachs for a tour of the south, where the Vlachs are concentrated; making the sign of the cross is a ritual for any Orthodox embarking on a journey, and they all asked me to do it again and again, so they could learn how to do it properly. All religions seem to have suffered equally, so much that today, no accurate statistics exist of Albania’s religious composition; although one often hears the prewar figures of 70 percent Moslem, 20 percent Orthodox, and 10 percent Catholic, the truth is that no one knows the real numbers, which are probably still too fluid to be set in type. Many are lapsed from the faith of their fathers, making Albania fertile ground for Christian evangelicals and Moslem fundamentalists alike, and both have sent large brigades there.

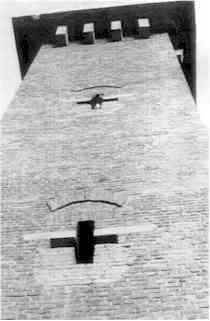

Bell tower of Orthodox cathedral Evangelismos in Tirana.

Note bricks knocked out of crosses, now restored.

Communist repression extended far beyond religion. Hoxha’s interior minister used to brag that one of every three Albanian citizens was an informer. People were threatened with fifteen years in prison just for saying that the store shelves were not full. For attacking Hoxha or his government, the term was said to be 25 years. The entire society was terrorized; one day as I spoke with a cousin in his house in Korēė, we heard a car pull up outside. He tensed up visibly, then laughed. Under the communists, that sound had been terrifying, because the few automobiles that did exist belonged to the government and the only one likely to pay a house call was the brutal secret police, the Sigurimi.

Although Albanians are intensely aware of the depredations of their former rulers, they seem almost disinterested in revenge. In contrast with several other formerly communist countries of Eastern Europe, there is no widespread movement afoot in Albania to go after the nomenklatura, the bureaucrats and informers who made the old system work. If there is any truth at all to the claim that one in three Albanians collaborated, the potential for disruption of Albanian society is great. But at the moment, Albanians are more preoccupied with sheer survival in a state whose economy and organs of government collapsed for all intents and purposes with the defeat of the former regime in early 1992.

Under the communists, some ten percent of the population (300,000 people out of about 3 million) served in the military — an extraordinarily high percentage. The United States, by comparison, has less than one percent (about two million out of 250 million), and for some of us, even that seems too many. Although we will probably never know the true military budget for Albania’s communist decades, it seems safe to assume that it devoured a huge proportion of the country’s very limited resources. Even at the time of my visit, one still saw plenty of red-cheeked soldiers.

But if there is a Hoxha legacy more ubiquitous than even the soldiers, it is the 800,000 concrete bunkers he built throughout the country to defend Albania against invasion by America, of all countries, as if we had nothing better to do than to storm tiny Albania. When the attack came, one or two Albanians was to jump into each bunker and, firing any weapon available, make the imperialist enemy pay dearly for every inch of Albanian soil. It is difficult to exaggerate the ominous psychological effect of these bunkers. Their design recalls a science-fiction robot: domed top pierced by a dark rectangular eye-slot, with stout cylindrical torso buried underground. They are eerie and they are everywhere — in fields and in mountains, on boulevards and on beaches, alongside railroad tracks, everywhere.

Today the bunkers are in disrepair, choked with vegetation or filled with debris. They stand as both symbol and metaphor for Albania under Hoxha: closed off, suicidal, under siege, alone in a sea of enemies, awaiting the final attack. They are also a reminder of the sheer indifference of rulers to ruled, for each bunker cost about 350,000 leks to build — at the time, half the cost of a very modest house. Had that money been invested in real construction projects instead of in Hoxha’s delusions, Albania’s failing infrastructure might have been renewed.

The greatest threat to Albania all along has been not America but Serbia, whose hardline nationalists claim Kosovo, a region within Serbia that is 90 percent Albanian, as the heartland of the Serbian people. In 1989, led by ultranationalist premier Slobodan Milosevic, Serbia withdrew the limited autonomy conferred on Kosovo by the Yugoslav Constitution of 1974. Instruction in Albanian was discontinued and the region was occupied by the Yugoslav Army and placed under a sort of martial law. The Albanians responded by teaching their children at home and boycotting Serbian elections, instead conducting their own and electing as their president a frail, 47-year-old academic named Ibrahim Rugova (not recognized by the Serbs). Mindful perhaps of the systematic slaughter committed by the powerful Yugoslav Army in Bosnia & Hercegovina, Rugova has set a peaceful course for political change in Kosovo and he has found a willing ally in Albanian President Sali Berisha. Their nonviolent vision is something of a novelty on this bloody peninsula and one can only hope it succeeds.

Bunkers like this litter both town and countryside throughout Albania.

My own greatest security concern when visiting Albania was not external but internal; I had read of widespread rioting, looting, and violence in the weeks before I arrived, but most of it ended after Albania’s first democratic election on March 22nd, 1992 (on that date, a new Parliament was chosen, which two weeks later elected Dr. Berisha president). Dislodging the old regime was like removing a painful tumor — the patient was soothed and able to rest. The calm was evident even to foreigners, but we three American Vlachs had an extra reason to feel safe in the phalanx of kinsmen that enveloped us as soon as we left the airport building. We were submerged within the group. This cut both ways: On the one hand, Albania was still not quite safe, and anyone who tried to mess with me would have to reckon with not one person but dozens; on the other hand, I had to submit to the demands and customs of my hosts, relinquishing to them some of my crotchety, absolute American sovereignty. It wasn’t easy, and I wasn’t always successful, but they may as well start learning what life is like in the kind of society they are seeking to emulate.

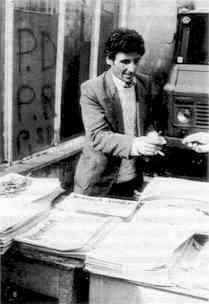

In communist Albania, private ownership of cars was forbidden, and as late as 1991 there was only a handful of private motor vehicles in the entire country; today, only one other modern symbol of freedom, the newspaper, is proliferating faster than the automobile — 17,630 cars entered Albania in 1992. At Rinas, a car hired by our hosts picked us up, delivered us to the hotel, and almost drove off with my luggage (the driver apologized profusely). There is one first-class hotel in Tirana, the choice of most international travelers, the Italian-built, low-slung Hotel Dajti; there is also a single second-class hotel, the tallest building in Tirana and all Albania, the fifteen-story Hotel Tirana. I had a room reserved at the Hotel Arbėria, a third-class hotel aimed at visitors from Eastern Europe and other impoverished countries — $25 per night, which to my Albanian friends and relatives seemed a huge sum of money. The Arbėria is designed in the spare, shabby communist concrete style that dulls the senses in every country of Eastern Europe. My room was cold and dark, the concrete floor barely covered with vinyl tiles and worn-out sections of linoleum of varying sizes haphazardly fitted together. The single bed consisted of a foam mattress suspended by a light wire mesh that offered no support whatsoever. The sheets were patched but clean, except for the mouse droppings right near the pillow. In the bathroom, the toilet paper was rough, the water closet leaked, and there were unexplained holes in the wall, but at least the shower fixture worked.

A new sight: freely available newspapers of every opinion.

My wife Caryn’s grandmother Kyratsa was born a year after my father in the same town and also came to the U.S. in 1916. She was 13 and left most of her family in the old country, including her parents, whom she never saw again, and a two-year-old sister, Bia, who still lives in Korēė. At the time I arrived, the two sisters hadn’t seen each other for 76 years.

Bia was waiting for me at the Hotel Arbėria, along with two nephews, Victor and Robert Stefa. As always, I am amused at the improvisation necessary to converse in our undeveloped language in the late twentieth century: Victor is a veterinarian turned meat inspector, but there are no such terms in Vlach, so he tells me he is a “doctor of beasts,” while Robert, speaking of foreign investment in Albania, describes offshore oil drilling as “pricking the ocean” and proudly tells me he has “a television with paint,” by which he means a color TV. I answered their questions for an hour or so, gave Bia a suitcase full of clothing and other American goods (few of my own relatives are still in Albania), and sent her off on the six-hour ride back to Korēė with some trepidation — on the way to Tirana the day before, their bus had passed no less than five automobile accidents.

It was twilight and I was exhausted after the long flight, but a large group of men from the new Vlach society eagerly awaited me at an apartment on the other side of town. We took a taxi to one of Tirana’s dirt roads, but we got lost looking for the building we wanted — they really do look alike. Finally we found the place and the young men immediately began toasting my arrival. The most common beverage in Albania is a strong liquor known as raki; having once seriously overdone it with the Greek version, called tsipouro, I can hardly stand even the smell of it. My new friends were surprised and, I think, more than a bit dismayed, as if they had never before met anyone who could not drink raki. Fortunately, there were also several bottles of a popular Greek orange drink on hand, and if I could not satisfy their desire for me to share their hard liquor, I made up for it with my ability to provide information, a very precious commodity in this closed society. I answered their questions about America (great place, but with its own set of problems), how I learned to speak Vlach (from my mother, who had just come from Greece when I was born), how many Vlachs there are in the world (perhaps 150,000, but they think there must be many more), and the salaries of various jobs in America (I countered their oohs and aahs with a sampling of our cost of living — food, rent, and so on).

By the end of the evening, I was as tired as I have ever been. We needed candles not only to make it down four flights of shoddy stairs but even to walk outside, for Tirana was pitch dark. We could not find a car but were lucky enough to catch a bus back to the hotel. I drifted off into a deep sleep only to be surprised at first light by the sound of a rooster crowing, right in the heart of this capital city of 350,000. On the street, there were other surprises: dirty children begging in tattered clothing; Protestant evangelicals in a van trolling for proselytes; the empty white pedestals of smashed communist monuments; and even some familiar faces — Vlach acquaintances from Western Europe and Greece also in town for the conference.

I spent that first full day in Albania, April 4th, a Saturday, walking around Tirana with Victor and Robert. We had lunch at a restaurant named Rogova, run by Albanians from Kosovo. Yugoslavia did far better economically under communist rule than Albania, and thus Yugoslav Albanians come from a fairly developed country, as opposed to the Third World conditions in Albania proper. The Kosovars also have capital to invest, while the average Albanian does not, and so they have formed a sort of bourgeois class in Albania and are at times rather resented. As we settled into a meal consisting of several different kinds of meats, Victor began to describe the methods used by some of his fellow meat inspectors; I lost my appetite but kept the momentum going by sipping a bottle of beer and answering questions. Vlachs all the way, Victor and Robert especially wanted to know about the family in America. They keep track of relationships up to third cousins and were astounded to learn that, having married Caryn, I did not know their entire family tree. The excuses I tried to offer (Caryn grew up in Bridgeport and I in New York; I have a poor memory) only managed to shock them further — in an oral culture like theirs, a poor memory is a luxury no one can afford, and the members of their family are anyway known for their extremely sharp memories. They are absolutely unreasonable about the need to remember things, and I know their genetic material so well that I am actually not surprised when they lean forward and admonish me in unison, “Put your mind to it.”

As an American walking the streets of Tirana in April 1992, I may as well have had two heads. But though Americans themselves were a novelty, American popular culture was well-known. As we ate at Rogova, Bob Dylan sang softly in the background; a sign in front of the Hotel Dajti mentioned “McHammer” (sic); and when the day had run its course and I returned to my own hotel, a highly amplified rock-and-roll group was playing live music at a club downstairs, curiously alternating songs like “Black Magic Woman” with Albanian melodies.

I woke up early Sunday morning, eager to see what would happen at the Vlach conference. The Albanian government had been kind enough to lend us a large auditorium in Tirana University. As Victor and I walked there, we met many people we knew on the street. The hall was packed with hundreds of people, and every country and faction was represented. The Vlachs have been in a precarious position as an ethnic group since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, when we were divided among Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia. Too few and geographically dispersed to even consider having our own state, we were claimed by Greece, to which we are linked culturally, and Romania, to which we are linked linguistically. This tug-of-war for our loyalties lasted from about 1860 until 1945, when the postwar Romanian communist regime decided to give up on us. With the overthrow of Romanian communism in 1989, however, the Greek-versus-Romanian debate resumed, joined by a third group that holds that we are neither Greek nor Romanian but just Vlach citizens of whichever state we happen to live in.

Meanwhile, our numbers have continued to dwindle. At the turn of the century, two British scholars who studied the Vlachs estimated our population at 500,000. The most recent survey, a book written in 1989 by another British academic, Dr. Tom Winnifrith — a Brontė scholar who has had a lifelong fascination with the Vlachs — figured the number of Vlachs at perhaps 50,000. But that was before Albania was opened up to western eyes.

Like everything else in the Balkans, population statistics are tied to history; indeed, if the peoples of the Balkans ever succeed in destroying one another, the cause of death can be listed in just one word: history. And only history can explain the question of Vlach population statistics. Albania was created just before the first World War and saved from dismemberment just after it by Woodrow Wilson, of all people. Serbia and Montenegro felt the northern part of the country belonged to them; Italy considered Albania its special colony in the Balkans; while Greece claimed southern Albania, which it began to call “Northern Epirus” as if a region by that name had always existed. Everyone has since given up on these claims except some extremist Greeks who are in any case not supported by their government. The basis of their argument is the Greek minority in Albania, known in Greece as Northern Epirotes. But when they reckon the number of their minority in Albania, Greek nationalists sometimes count all the Orthodox, regardless of whether they are Greek, Vlach, or Albanian.

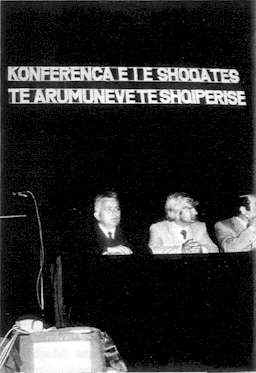

Dais of the Conference of the Aromanian Society of Albania

Today, the Greeks claim to have anywhere from 50,000 to 350,000 compatriots within Albania. Several Vlachs in Albania told me that there are only 50-100,000 Greeks, while there are 200-300,000 Vlachs. I honestly do not know whom to believe, and conditions being as they are in Albania, it will be some time before a reliable census is taken. Only one thing is for sure: even together, Vlachs and Greeks today comprise a rather small portion of Albania’s population.

The conference of the Albanian Vlachs began in an orderly way. Since people from the village of Selenitsa provided the main impetus for the creation of an ethnic society, they predominated on the board, which was seated at a dais on the stage of the auditorium. There were even a few women, and goodwill was evident everywhere. But the dynamics of a traditional society are very simple: traditions, rituals, and customs bring a modicum of order to an otherwise chaotic world. Say we are living in a village hidden way up in the Pindus mountains, out of the reach of any civilization or law; what is to prevent me from killing you, raping your daughter, or stealing all your livestock? The consensus afforded by tradition — that’s all. It’s the only thing that keeps the lid on such a society; and when the lid starts to blow, watch out. As we all know, it blows rather often on this peninsula. Maybe this has something to do with the mobility of the modern world: it is possible, though difficult, to keep an entire village hewing to the same tradition, but imagine the problems when you meet people from another village, or another region, or another country, or another continent, whose traditions do not match your own? All of a sudden, the lid no longer fits.

So the Vlach conference worked splendidly for as long as a consensus was maintained, and then it spun quickly out of control. Once these meetings go out of control, they assume the nature of a bidding war: Someone on the stage says something that so unnerves a member of the audience that the latter feels he must stand up in his seat and disagree; hearing shouts of approval from the audience, another person is emboldened to stand up and outbid the fellow before him with an even more radical idea (or a more radical statement of the same idea); and so on. Such meetings offer a flash of insight into the process of radicalization at times of chaos — all of a sudden, you see before you not Costa and Spiru, but Danton and Robespierre, or Trotsky and Lenin. I am filled with awe for the achievement of modern institutions like political parties, the U.S. House of Representatives, the Society Farsharotul, or even whole countries, which manage to stay together by creating a consensus for a new tradition.

The pro-Romanian faction had prepared itself well and the speaking program included the Romanian ambassador to Albania, who spoke of the Vlachs and Romanians as “one people”; a Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan who promised to build churches for the Vlachs; and a Romanian Senator from Transylvania whose nationalist party enjoys the support of many hardline members of the Vlach emigrant community in Romania. But while the Romanians either spoke in Albanian or required translators from Romanian into Vlach, the Greeks had the presence of mind to see that their delegation was entirely Vlach (led by the Mayor of Metsovo, the largest Vlach town in Greece) and spoke our language perfectly. The loudest incident of the day occurred when the Romanian Ambassador was allowed to speak before the Mayor of Metsovo, which was considered a grievous insult by the Greek Vlachs — “How could you put that foreigner before un di a nostru (one of our own)?” The entire Greek delegation staged a noisy protest at the foot of the stage, drowning out the Romanian ambassador until they were promised that the Mayor of Metsovo would be the very next speaker. This man, Aleko Kakrimani, spoke so eloquently, succinctly, and non-politically about the bonds between Greek and Albanian Vlachs that he almost brought the house down (it didn’t hurt that people from Metsovo speak a particularly melodic version of our language).

Although pro-Greeks and pro-Romanians later engaged in more bitter polemics outside the conference hall, it turned out that they were little more than a sideshow, for the vast majority of Vlachs in Albania think of themselves as neither Greek nor Romanian but simply as Vlach citizens of Albania. I found this everywhere I went, even in Korēė, where at the turn of this century emotions had run strongest on both sides, pro-Greek and pro-Romanian. The leadership of the Albanian Vlach Society has followed this non-partisan line despite pressures and blandishments, earning if nothing else the goodwill of the Albanian government, which would no doubt view the Vlachs differently were a nearby state to claim their loyalty. And by repeatedly emphasizing this position, these leaders skillfully kept their conference on track despite all the fireworks.

I have by now served on enough boards and attended enough conferences to know that the most important work often takes place before or after the regularly scheduled activities, usually at the luncheons and repasts that accompany such events. The Vlach conference was no different; after the formalities were concluded, we walked back to the Hotel Arbėria for a banquet that is lavish by many standards, especially those of Albania in early 1992. It was there that I got to meet everyone face-to-face; it was there also that most of the real deals were made and schemes hatched. There were some bright spots, like Orthodox Archbishop Anastas, who spoke very openly about letting the Vlachs celebrate the liturgy in their own language, a position never before heard from a Greek prelate. There were also some dark spots, like the attempt to create a “Balkan Federation of Vlach Societies” without the Greek Vlachs — indeed, without any semblance of a democratic debate (the discussion was held behind closed doors by “intellectuals,” the second most dangerous class of human beings in the Balkan Peninsula after men in general). I found out about the meeting quite by accident, went into the room, and stood alone against excluding the Greeks; the consensus was damaged and it soon ruptured on another issue. A bidding war began, no new consensus was achieved, and the meeting broke up when someone made the face-saving comment, “We get fired up and all of a sudden we want to do everything under the sun in one day.” The banquet ended with many a warm embrace and a few cold stares; I went up to my room but had trouble falling asleep, not only because of the turmoil of the day’s events, but also because I was filled with anticipation about embarking the next day on a weeklong tour of southern Albania.

In the morning we drove west to the seaport of Durres, where we turned south, following the coastal plain to another port city, Vlorė. Durres is relatively prosperous, as evidenced by its many new cars and decent buildings; like Constantsa, the great Romanian harbor on the Black Sea, it has climbed a notch above the surrounding poverty because of its maritime tradition. Many young men from Durres became sailors, one of the few classes to hold western hard currency in communist times — they needed it to buy supplies in the various ports they visited. Moreover, in the final days of the Alia government, thousands of people tried to escape Albania by climbing aboard Italian vessels in Durres harbor; those who made it to Italy and found work began to send money back to their families in Durres, and these remittances have contributed to the town’s prosperity as well.

Byzantine mosaics deep in the underground corridors

of the Roman amphitheater at Durres.

Another thing Durres has in common with Constantsa is its antiquity; in ancient times, Durres was a Roman port named Dyrrachium, Constantsa the Greek town of Tomis, and both are littered with ancient monuments. In 1966, an Albanian resident of Durres was uprooting a fig tree in his back yard when he came upon something that looked like brickwork; excavation revealed the existence of a huge Roman amphitheater. A whole neighborhood had been built on top of it. Thus far, 34 houses have been removed, revealing one-third of the edifice. To give some idea of its size and of the Roman population in that part of Albania in antiquity — and this sheds some light on the origins of the Vlachs — the amphitheater held 15,000 spectators; the current soccer stadium of Durres holds only 5,000. Entryways and corridors within the amphitheater were later converted to Byzantine churches and chapels that still bear striking mosaics and frescoes, and burial vaults have also been found, but archaeology is a luxury in Albania right now and excavation has ceased. Perhaps a western university will become interested in the site.

We left Durres and headed south. Driving along the simple two-lane highways of Albania is actually quite an adventure; motor vehicles are a new thing and neither people nor animals are in the habit of looking out for them. Although there were some close calls, we did not hit any people, but the birds of Albania seemed to be intent on using our car as an instrument of suicide, so often did they fly into our radiator grill.

The coastline north of Durres is rocky but to the south it is sandy and, save for the occasional bunker, essentially unspoiled — a Mediterranean developer’s paradise. This was quite a contrast with Vlorė, which has clearly not fulfilled as much of its maritime potential as Durres. I was relieved not to be staying there overnight; our destination was a household in a partly-Vlach village in the mountains just inland. We arrived there and were greeted by our hosts, an elderly widow, her handsome 25-year-old son, whom I’ll call Spiru, and Spiru’s wife and infant girl. It was a very traditional family and Spiru’s wife was so deferential that I never even learned her name. To be fair, this was not due only to her reticence; in the patrilineal genealogy of the Vlachs, the wife is considered to have married into the clan of the husband, and she is forever addressed by the husband’s family and friends as nveasta — “the bride.” The downside of this, of course, is the subsuming of female to male identity, but some see an upside in still being considered a bride at 60.

Spiru had earned money working in Greece and his household had an air of prosperity. Greek visas are worth thousands of dollars in Albania, so great is the need for employment that will earn hard currency. Greece has taken to offering visas to the Vlachs of Albania, who have only to accept the designation “Northern Epirote.” This is a brilliant move on the part of the Greeks; they could strengthen the Greek minority if they could count the Vlachs as Greeks, and what better way to do so than to reward people with a visa? Spiru is one of a growing number of Vlachs who have taken advantage of this offer. He recognizes that by calling himself something other than Ruman (or Aruman) — the self-designation of the Vlachs — he has become an instrument of Greek foreign policy. But he has a family to support; and Greece is a nice place to live and to work; and when he’s done, he’ll return to his family and household in Albania; and anyway, he knows what he is, no matter what his Greek identification card may say; and so you can move one more Vlach from Column A (Vlach or Albanian) to Column B (Greek). This is the way things go in the Balkans.

Spiru actually represents the greatest hope of Albania — hardworking young people who go wherever they can to earn money to send back to their families. He will do any sort of work offered him, at the best wage he can find. Even though Spiru plans to return to Albania, he reminds me of my father, who routinely sent his American earnings to his family in the old country until he had his own family to support. That Albania is surviving the collapsed economy of its first year of freedom is due as much to foreign remittances as to humanitarian aid.

It was in Spiru’s house that I first noticed something that I would see in many other Albanian households. It looked like a paper sculpture with a design resembling a 360 degree fan. I was surprised and delighted when I was told that it was a book by Enver Hoxha with its pages folded to create a pattern; this tradition seems to have sprung up spontaneously after the fall of the communists. Perhaps the greatest growth industry under the old regime was publishing the works of great communist leaders, especially Enver Hoxha. With the birth of democracy in Albania, however, his books were converted to two new uses: these sculptures, which turn something ugly into something almost pretty; and toilet paper, which does not.

One of two remaining uses for the books of Enver Hoxha.

We had a wonderful dinner of several courses — Lord knows Albanians cannot afford to eat like this themselves, but they spare nothing for a guest — and then went to bed. We arose the next morning to a raging storm of perfectly round white hailstones the size of dimes; by the time we were ready to depart, the hail had turned to a driving rain so dense that a young boy who ventured to step out into it was soaked within two seconds. We decided to continue our journey despite the downpour.

I was given the seat of honor in the front, next to the driver — this happened everywhere I went in Albania. The first thing I noticed was the driver’s brand of cigarette, Jugoslavia; There’s one brand name that won’t last very long, I thought to myself. While our previous driver spoke only Albanian, this one also knew some Greek, so I was able to communicate with him (I am fluent in Vlach and conversant with Greek and Romanian), though not quickly enough to prevent the mishap that soon befell us. At one point, the road we were on crossed a small stream, which made its way under the highway through a large conduit. The rain had so swollen the stream that it had overwhelmed the conduit and burst across the road. Our driver nonchalantly plunged right into the raging torrent, which was already about two feet deep. The distributor got wet, shutting down the engine and leaving 5 people in a very small car in the middle of a thundering red-clay river that was rising perhaps an inch a minute. We were taking in water. The next thing I knew, Spiru disrobed down to his underwear and jumped out of the car. A wave of water swept in as he opened and closed the door. He made his way to the front of the car and singlehandedly pushed us up a slight incline 20 feet to safety. Even considering the buoyancy of the car at that point, this was still an extraordinary feat. These mountains produce hearty people; had our fate depended on this city boy’s reflexes, for example, I am certain the consequences would have been far worse.

We dropped off Spiru in Vlorė — he was almost completely unfazed by the incident, as if it had been all in a day’s life in the mountains, and probably it was. We went on to the famous town of Tepeleni, home of Ali Pasha, “the Lion of Iannina,” an early-nineteenth-century Ottoman lord of Albanian origin made famous by Lord Byron in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Not much remained of the castle Ali Pasha had built there. The great pasha had started his climb to fame as a brigand on these very roads, and in Tepeleni I heard a story about a modern-day successor. When private cars began to appear on Albanian roads again, a fellow had taken to stopping them at gunpoint just outside Tepeleni and robbing the passengers. One of his victims did not take very kindly to this, however, and returned and ran him down with his car. End of story.

A member of our party, a Vlach academic, had planned a luncheon for us with two friends in Tepeleni, both doctors. I was amazed to see them both smoke and drink raki just as liberally as any Albanian male, especially since one of them was a specialist in lung diseases. Lunch for 5 here cost a mere 105 leks. Midway through our meal I needed to use the toilet, but when I inquired I was told there was none. So surprised was I that I asked again. We were at a restaurant in the woods just outside of town and, of course, it was still raining. There was no alternative: out into the woods I marched, umbrella in hand.

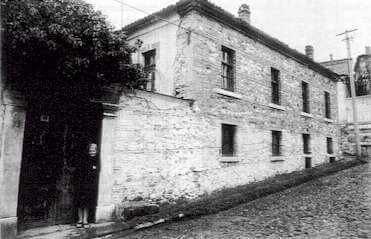

Our next stop was Gjirokaster, a town of 25,000 built on the side of a mountain and my favorite site in Albania. Perhaps because it was Enver Hoxha’s home town, it was well preserved and almost entirely free of communist concrete blocs. Quaint old shops face each other across steep cobbled streets. It has a sizeable population of Greeks, who call the town Argyrocastro. High above the town there is a castle built by the Byzantines in the 12th century atop the walls of the original settlement, which themselves date from the 5th or 6th century A.D. The conquering Ottoman Turks built the castle higher; Ali Pasha added more when he ruled the region; and on top of that, Ahmed Zogu, Albania’s king between the two world wars, built a small prison which was also put to use by Mr. Hoxha’s secret police (a member of our party told us of an uncle who was hung by his ankles and tortured there for 27 days) — making this castle yet another metaphor for Albania, a diachronic sort of bunker. Hoxha’s house has also been reincarnated, first as his local villa, next as a sort of Hoxha Museum, and now as a Folk Museum.

The mountains around Gjirokaster are dotted with many small villages; we aimed to stop in one of them, Andon Poēi, whose history is typical of how villages form and disperse in the Balkans. Andon Poēi used to be Albanian, but during World War II its residents (and those of many of the villages around Gjirokaster) fled the guerilla warfare in the mountains and settled in cities. Vlachs in need of mountain pastures came from throughout Albania and northern Greece and resettled the village. Each family lived in a kind of grass hut known as a kalyva until 1960, when the modern village was built. By “modern” I mean contemporary, for there is nothing modern in any other sense in Andon Poēi. The road leading to it is little more than a rutted track of such varying quality that when we briefly hit 15 miles per hour it felt as if we were speeding. As far as I know, no home has indoor plumbing, and even the outhouses are primitive. But the villagers are wonderful, hospitable people, and they were absolutely delighted to meet an American who spoke Rumaneashti, our word for the Vlach language, which, owing to the guttural French-style “r” of the Vlachs in Albania, starts out sounding like a growl, Rrrrmaneashti. I was fed huge quantities of bread, cheese, mutton, and potatoes and was toasted every 5 minutes with raki, the only beverage in town. I think I must have met all 1,000 villagers by the evening’s end; at least, I felt as if I had, and, bundled up against the cool mountain air in several layers of thick wool blankets, I quickly settled into very sweet slumber.

I was excited when I awoke; our next and last stop was Korēė, my father’s home town. Actually, he was not from Korēė but from a tiny village named Pliassa. There used to be two Pliassas, a Vlach village on a mountain just outside Korēė and an Albanian village at the foot of the same mountain; only the lower village still exists. The Vlachs were once transhumant shepherds, spending the summer in a mountain village and the winter in a town in the lowlands but always considering the mountain residence their true home. Korēė was my father’s winter town, but Pliassa was his home.

My father told me about the wolves and bears in the mountains, and particularly one encounter with a wolf when he was a boy — he never saw the wolf, only heard it howling nearby as he walked along a mountain path one moonlit evening. He also told me over and over about an Albanian “revolution,” but this confused me because it wasn’t like the American revolution; I learned much later in graduate school that this relatively minor incident in the overall scheme of international affairs took place during a period of near-anarchy in Albania between the start of the Balkan Wars in 1912 and the end of World War I in 1918. This “revolution,” however, was the defining moment of his life — indeed, the defining moment in the life of most of the members of his clan: the cold-blooded murder in 1914 of his father’s first cousins, the priest Haralambie Balamaci and his brother Sotir, by pro-Greek nationalists in Korēė.

The Balamacis are part of a large Vlach tribe known as Farsharots. Like so many other aspects of Vlach history, the source of this title is uncertain; it is thought to come from the Albanian town of Frashari, but it is not clear that the tribe was ever based there. Haralambie Balamaci (also known by the honorific title Papa Lambru) was born in 1863, one of a number of priests in the Balamaci family. He had been raised in Greek Orthodoxy (a Greek church was built in Pliassa in 1801), but in 1860 the Romanian government, motivated as much by romantic nationalism as by the need for more chips in its bid to become a player in Balkan power politics, had begun its campaign to bring the Vlachs under its influence by building churches and schools for them in and around the Vlach heartland of Macedonia, which was then still under Ottoman control. The Balamacis were among the strongest clan in their community, largely because of the great wealth in sheep possessed by Haralambie’s uncle, Spiru Balamaci; once they were won over to the Romanian cause, almost the entire Farsharot tribe came with them.

Haralambie renounced the Greek church and began to celebrate the liturgy in Romanian, which he and others believed was the Vlachs’ “literary language.” This upset the local Greeks and pro-Greek Vlachs and Albanians greatly. When the Ottomans ceded Thessaly to Greece in 1881, many Albanian Vlachs were cut off from their winter pastures by the border change; Papa Lambru joined his uncle Spiru in a Vlach delegation that lodged a protest with the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul. This upset the pro-Greek Vlachs and Albanians of Korēė still more and ten years later, when Papa Lambru again traveled to Istanbul, this time to request the creation of a Romanian Episcopate in Vlach regions, an attempt was made on his life.

This was the period of a savage guerilla war between pro-Greek and pro-Bulgarian forces over who would get Macedonia once the Turks inevitably pulled out. In southern Albania, the pro-Romanians tended to side with the pro-Bulgarians against the Greeks. (I am told there were very few ethnic Greeks in Korēė, though there were enough pro-Greek Vlachs and Albanians to sustain a Greek Orthodox Cathedral there. There were definitely no ethnic Romanians.) Tensions grew between pro-Greeks and pro-Romanians. In 1905 the Greeks sent a band of guerillas led by a pro-Greek Vlach named Gouda to Pliassa to discourage the use of a Romanian liturgy in the church named Saint Mary (in Vlach, S’ta Maria); he burned the liturgy books, but worship in Romanian continued. In 1906, the Greek Bishop of Korēė, Fotios, decided to visit Pliassa and personally change the language of the liturgy from Romanian to Greek. He was warned not to go and was stoned when he arrived, which so enraged him that he excommunicated Papa Lambru and all of his supporters. Papa Lambru went directly to Pliassa and held a service in Romanian to rally his people and then he bought a house in Korēė and started his own Romanian school there. In retaliation, Fotios barred all pro-Romanian Vlachs from the Greek church in Korēė; Papa Lambru promptly began holding services in the house, in Romanian, galling Fotios still more.

Later that year, Fotios was assassinated by a Vlach named Thanas Nastu, who escaped to Romania. Turkish authorities rounded up several Balamacis and put them in jail but were unable to link them to the crime. In 1908 the new Greek bishop of Korēė repeated the rite of excommunication, but the victory of the Young Turks in the same year and their repression of all Balkan ethnic groups alike led those groups to unite in a final revolution against Turkish rule in the peninsula. The Balkan Wars of 1912-13 prised most of Turkey in Europe away from the Ottomans but although the Greeks won much of Macedonia, they also desired southern Albania (“Northern Epirus”). Greek troops occupied the region and the local pro-Greek faction was ecstatic, fully expecting union with Greece. But the mysterious ways of Great Power politics defied their expectations, and in the middle of March 1914 they learned that Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos had concluded an agreement with the Powers wherein Greece gave up its claim to southern Albania and instead received the Aegean Islands (Chios, Mytilene, and others). Greek troops were to withdraw from Albania by March 31st.

In the months before, Papa Lambru’s life had been threatened several times. Albania was in a state of near-anarchy, and he had become a virtual prisoner in his own household, afraid to come out even to shop. The pro-Greek faction of Korēė detested him and when they saw that, partly as a result of his efforts, their cause was being lost, their anger no longer knew any bounds and they cried out for his blood. Early on the morning of March 23rd, 1914, a group of some 60 armed men surrounded the house where Papa Lambru and his brother Sotir lived with their families. They shouted that if the priest did not come outside, they would burn down the house. Papa Lambru came out, followed by Sotir, who refused to leave his brother’s side. Their pockets were emptied and the contents replaced with pictures of Fotios, the assassinated Greek Bishop. The two brothers were marched to a piece of high ground just below the Orthodox church of St. Elias (called Shin d’Ili in Vlach, a corruption of the Albanian Shen Ilia). Sotir’s wife and son followed at a distance. Along the way, Papa Lambru and Sotir were kicked, beaten, tortured, and stabbed. When they neared Shin d’Ili, they were tied to trees and shot dead. Their bruised and bullet-riddled bodies were kept on display there for three days.

The bodies of Haralambie and Sotir Balamaci lie in state before burial.

Kneeling at center is Papa Lambru’s son Nicutsa.

My father was 12 at the time and he came to America two years later with this memory etched deeply in his mind. No wonder he spoke of it so often. Pliassa was soon abandoned by the Farsharots, giving rise to one of the largest and most far-flung diaspora communities ever produced by a tiny Balkan village. Before 1920, many emigrated to America; after 1920, others were lured by Romania to settle in the Southern Dobrogea, a region acquired from Bulgaria after World War I. There were very few Romanians among its population and the idea was to use the Vlachs to colonize the region for Romania. But less than two decades later Romania was forced by Hitler to cede the Southern Dobrogea back to Bulgaria, uprooting these Vlachs yet again and radicalizing them in the process. Many never forgave the Liberal Romanian government then in power; this community soon became a fertile recruiting ground for the Iron Guard, the Romanian variant of Nazism and Fascism, and Vlachs eagerly manned its death squads and were responsible for some of its most spectacular assassinations, which often targeted Liberal party leaders.

By this time, only a rump of the Farsharot community remained in Korēė. Vlachs from other tribes began to move into the Vlach quarter of town, in the continuing process of communities coalescing and coming apart. Pliassa itself had only come together in the 18th century, after Ali Pasha and other Albanian chieftains had sacked several important Vlach centers, including the great town of Moskopolje. Who knows from which of these places the Balamacis had come when they found refuge in Pliassa? There is family tradition that the name was once pronounced Bulamaci, then Balamaci; a branch of the family moved south into Greece, where their name became Balamatsi (Greeks cannot pronounce the “ch” sound and so change it to “ts”). Another group went west to the Macedonian town of Bitolja, where their name became Belimace; some of their descendants moved to Romania and kept that name, while just recently I met a descendant of another branch of that family that had ended up in Greece as Bilimatsi.

There are only a few Balamacis left in Korēė: one descendant of Papa Lambru, his granddaughter Marioara Balamaci, who is elderly and unmarried; and the rather more plentiful descendants of Papa Cota Balamaci, the man who was quickly ordained a priest in 1914 to take Papa Lambru’s place (some say he had been a bandit until then, but the bandit who becomes a priest is a popular paradigm in Balkan storytelling). When I visited Korēė, I stayed with my wife’s relatives, the Stefas; I suppose that as first cousins of my mother-in-law, they were more entitled to host me than Marioara Balamaci, who is my third cousin. The Balamacis, the Stefas, and most remaining Farsharots live in the old Vlach quarter of town, located on the outskirts at the foot of a hill; many of the houses there are essentially as they were when my father left in 1916, and as I walked through the town my head swam with his descriptions of the small private courtyard attached to each house, the whitewashed walls, the cobbled streets, the fountains, and the cold air (Korēė is 700 meters above sea level).

After a quick series of visits and another grand dinner, I had begun to feel a flu coming on and made a deal with everyone in the household to let me sleep late the following morning. But of course I was awakened very early by an exuberant Vlach voice shouting, “O, lai Nikolao! Niko! Niko! Niko!” The voice turned out to be that of my cousin Salvatore Balamaci, who was too excited about having an American relative in town to let the morning be wasted on sleep. And so it went throughout my entire stay in Korēė — I was bedridden with the flu and unable to visit people, so a steady stream of relatives came to call on me. My greatest regret was that I could not make the pilgrimage up to the ruins of Pliassa.

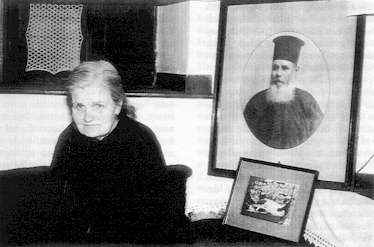

Marioara Balamaci next to a photograph of her grandfather,

Papa Lambru Balamaci, in her house in Korēė.

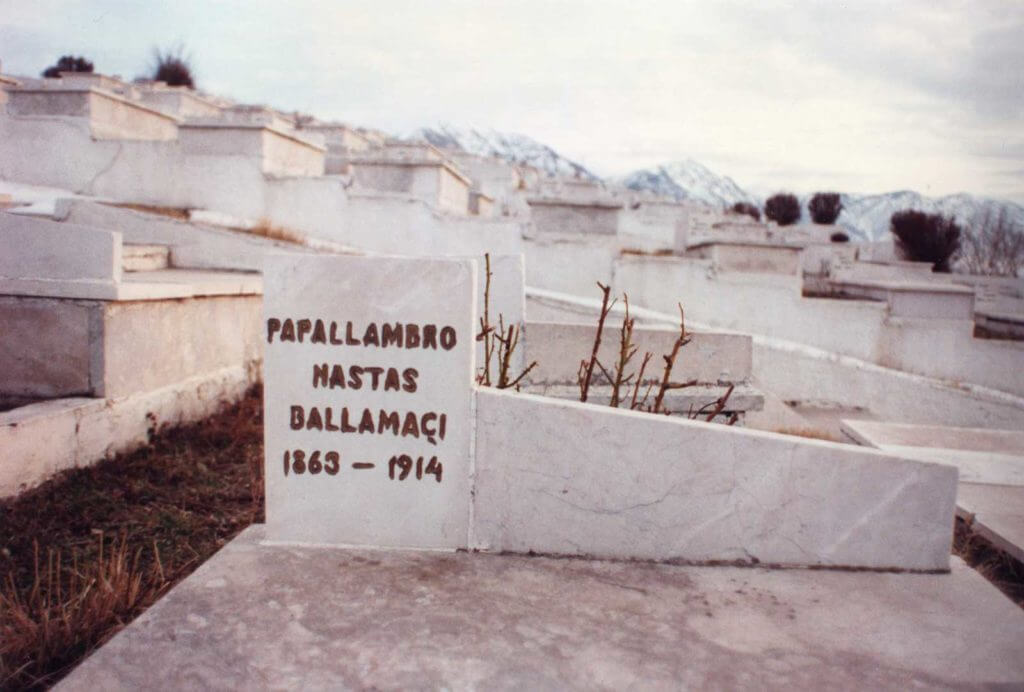

I spent an extra amount of time with my cousin Marioara, who is a sort of family historian (she also possesses a treasure-chest of old family photographs and letters and diaries of Papa Lambru and other Balamacis, including some letters from my own father). It turns out that the story of Papa Lambru did not end with his death in 1914. The Romanian school in Korēė, like the entire pro-Romanian movement among the Vlachs, lasted until the second world war. In 1925, with the help of remittances from the Vlachs in America, Papa Lambru’s small chapel had been replaced with a Romanian Orthodox Cathedral, St. Sotir, but a severe earthquake in 1931 essentially destroyed it and the community was reduced to using a small makeshift chapel erected just behind the crumbling cathedral. In 1959, the Chief of the Communist Party Committee of Korēė decided to pull down the rest of the church structure so the land could be used for something else; Papa Lambru’s bones were also buried on the property and Marioara insisted that they be exhumed and reburied in another cemetery. But the Party Chief was a descendant of one of Papa Lambru’s killers, and in an all too typical act of Balkan hatred he not only exhumed the bones but broke every single one of them. Marioara calls this the second murder of Papa Lambru. She reburied the bones herself and 3 years later, in 1962, at his new grave, Papa Lambru was honored as an Albanian hero for resisting the Hellenization of the Orthodox of southern Albania. In 1970, a majestic new Heroes’ Cemetery was built high atop the hill behind the Vlach quarter, and Papa Lambru’s bones were moved to a marble-covered crypt in a prominent position there; a street in Korēė was also named after him — the street where he used to live, in the house now occupied by Marioara.

Papa Lambru’s grave in the Heroes’ Cemetery overlooking Korēė.

My own ideas about the Vlachs are rather different from those of Papa Lambru. I don’t think we are Romanian. I see the pro-Romanian movement, well-intentioned though some of its supporters may have been, as just another attempt to assimilate us to a non-Vlach national culture. I have little patience for nationalists, Vlach or any other kind. Nor do I have the visceral hatred of Greeks that the pro-Romanians have; quite the contrary, my mother is from Greece and I’ve always had a special fondness for that country — I even made it a point in college to learn to speak Greek. I sometimes feel guilty that my views are so different from those of Papa Lambru, and I try to salve my conscience with the thought that though non-nationalist ideas like mine may not save our small culture, they are probably the only way to put an end to Balkan atrocities like his murder — and like the unspeakable horror being visited on the people of Bosnia today. It seems to me that it is deeply held ideologies, not the lack of them, that animate the greatest crimes.

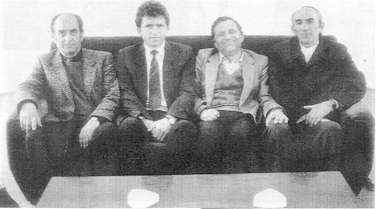

Some of the main figures in the Albanian Vlach Society: (from left)

Ianku Balamaci, Rrapo Zguri, Dr. Spiro Shituni, and Victor Stefa.

During my week in Albania, Sali Berisha, a cardiologist and leader of the opposition to the communist regime, was elected President — the first democratically-elected leader in the history of that country. It was an extraordinary experience for Albanians, and even an outsider like me was able to feel some of the excitement and emotion. While I was in Korēė, the television replayed again and again the election of Berisha, the applause of the Parliament, the acclaim of the people. It was a transforming national experience, evocative of the election of John F. Kennedy in the United States, everyone watching, everyone hopeful. In his acceptance speech, Dr. Berisha announced that he would not reside in the Presidential Palace but rather among the people, in the modest Tirana apartment he and Mrs. Berisha shared with their teenage son and daughter. Throughout Albania, people were moved to tears, but few more than Victor and Robert, who watched Berisha intently and translated his words for me.

Their father had been a prosperous pharmacist in Pogradec, a resort town on Lake Ohrid. The communist regime had confiscated his pharmacy and put him to work in it. But on January 10, 1951 they accused him of “economic sabotage” and put him in jail. The specific charge was even more ludicrous: they charged him with planning to poison the water supply of Pogradec and kill everyone. They kicked his family out of their seaside villa and condemned him to hang, but after 11 years in various prisons throughout Albania, he was released and lived another 23 years, until 1985. His story is all too typical, and as Victor and Robert studied the figure of Sali Berisha on their television screen, they could hardly believe that the nightmare was over, that their father was vindicated.

The return to Tirana was anticlimactic. When I arrived at Rinas Airport, an Albanian who was returning to New York on the same flight shouted to me, “I saw you on television!” (the Vlach conference had been televised, another gracious gesture by the new Albanian government). The in-flight movie, Frankie and Johnny, is one of my favorites and helped prepare me for the cultural shock of returning to New York. Caryn awaited me at JFK; it was good to be home, but strangely, I found my sudden anonymity a bit disconcerting, like a celebrity unrecognized.

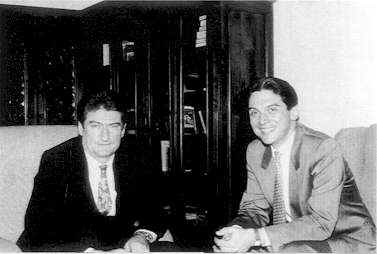

The writer with Dr. Sali Berisha, President of Albania.

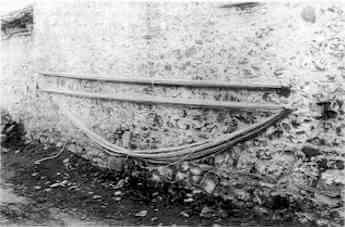

Nine months later, in January of 1993, I returned to Albania to help Sali Berisha build his press office up to western standards. You just never know where life is going to take you. During my 4 weeks in Albania, the sun shone every day but one, and even the one exception was perfect, the day I climbed up to Pliassa inside a snowcloud — it gave the scattered stones of my father’s village an aura of immateriality, figures appearing from the mist as ghosts, a shroud still preserving Pliassa’s mysteries. Rinas Airport was fenced in, free of livestock, and almost pretty. The lek had stabilized at about 100, both on the street and in the bank. Ramiz Alia was under house arrest, and Enver Hoxha’s widow Nexhimije was just at the end of her trial, both charged with relatively minor things like embezzlement and unauthorized expenditures. Wages had increased to about 2,000 leks for a laborer and 3,000 for a professional. The military budget had been slashed. But the cost of a meal for 3 at Rogova had risen from 620 leks to 2580 leks. Tirana residents were used to foreigners and it was possible to walk the streets in something resembling normal urban anonymity. Bia and Victor had finally made it to America in November, when my son Andrew was born. And although I now have a few Albanian stories of my own to tell him, I want him also to know about his grandfather, who left Albania in 1916…

Sections of walls like this one are all that remains of Pliassa.

Note: An excerpt from this article was published in Illyria, June 1993. The full version is scheduled to appear in the September 1993 Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora.

“Better an ounce of luck than a pound of intelligence.”

–Albanian saying

Views of Korēė:

Street named after Papa Lambru Balamaci

typical doorway — note architectural details, indicating past prosperity

Land of contrasts — sheep grazing in front of Tirana’s modern Hall of Culture.

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Vlach merchant George Caporan selling traditionally

crafted rug in the town square of Korēė

Marioara Balamaci standing in doorway

to her house on Papa Lambru Balamaci Street.

The side of a house in the Vlach quarter of Korēė, Albania. Traditional woolmaking crafts survived comunism; now their greatest challenge is to survive and prosper in capitalism.

Enjoyed your article!

Thanks, Helen!

Thank you very much for this article!

Thanks, Marie! I have since found a document that lists all the others killed on the same day Papa Lambru and Sotir Balamaci were murdered — I remembered Caryn’s muma Vasilikia (Cipu) Teja telling me that a younger relative (sister?) of hers was among them but I’m not sure. I will try to find a way to post it as an addendum to this article.